1906 Cadillac Model K

Words Paul Owen | Photos Tom Gasnier

Phil henley’s 1906 Cadillac Model K marks more than 113 years of motoring history in this country. It also shows how kiwi expertise can improve the breed

New Zealand was still a British colony when this single-cylinder Cadillac Model K first rolled out of Henry Leland’s Detroit factory 113 years ago. Partial independence would come with New Zealand’s shift to Dominion status in 1907, while the right to determine our own foreign affairs wouldn’t be granted by the Brits until 1947.

Phil Henley’s beautiful, turtle-backed, brass-embellished American veteran is therefore a car that’s older than our nation. It’s also one of the oldest cars still running on our roads. Phil is a passionate member of the Horseless Carriage Club of NZ (see sidebar), so has a pretty good understanding about where the Cadillac sits in the list of cars here that have the longest history.

“The oldest car in New Zealand is the 1895 Benz in the Southward Museum, while the oldest car owned by any of our members is a 1901 Locomobile Steamer. A good number of our members own Model T Fords.”

Such are the mechanical similarities between the Model T and the early Cadillac that a conspiracy theory voiced by some veteran car enthusiasts identifies Henry Ford as the designer of the latter. The theory is founded on Henry Leland’s involvement in the 1902 liquidation of the Detroit Motor Company, one of Ford’s earliest enterprises.

Ford had already begun planning the car that would make him a household name at the time of said liquidation. He immediately left the company to complete the project, while Leland put a similar car into production in 1903, and named the brand it bore after the French founder of the city of Detroit, Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac.

There were two key advantages to buying the Cadillac instead of the Ford. The first was the 10-bhp single-cylinder, copper-water-jacket-cooled engine that Leland had virtually perfected during his previous work for Ransom Eli Olds(mobile), which would soon establish an enviable reputation for reliability. The other was all the experience Leland had gained in parts manufacturing during his time with firearms manufacturers, Colt and Springfield. There, he had learned the value of tight tolerances and ensuring that every part was interchangeable.

Through his experience in shepherding the development of precision machine tools like the Brown and Sharpe Universal Grinder, Leland could ensure that Cadillac parts were made to a tolerance of 0.001 of an inch – a level of precision and interchange-ability virtually unheard of before. That precision enabled Leland to build some of the sweetest-shifting transmissions of the time. As a result, early single-cylinder Cadillacs quickly became desirable.

With few modifications such as the addition of a false front engine ‘bonnet’ for extra storage, and a shift to a tractor-inspired articulated front end with a transverse leaf spring, about 30,000 would be made between 1903 and 1908. Many of those sales were driven by the market’s thirst for reliability during the dawn of motoring.

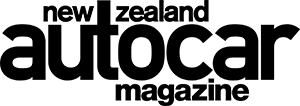

“It’s amazing how competent this car is (for its age),”says Phil, after the mid-mounted, rear-facing, 1.6 litre horizontal single chuffs into life upon his second swing on the crank handle. Some of that competence is due to the modifications made by the car’s previous owner, Ray Officer, of Te Awamutu. The right-hand drive car spent a lot of its life as a collection of rusty bits, and all of its early history has been lost.

Various other Kiwi owners never quite got to grips with the getting the Caddy back on the road, but Phil says Ray could apply some clever engineering skills to the task, and had ready access to all the resources required to complete the project. The end result of Officer’s ownership is a car that’s much improved on the one originally envisioned by Henry Leland. “It probably makes significantly more than the original 10 horse power, as Ray would have undoubtedly bumped up the compression ratio to take advantage of the better fuel available now and these days the engine can be tuned differently for the same reason.

“Fuel back in the old days was absolutely dreadful, very low octane and mixed with lots of kerosene.” The engine’s internals also benefit from changes in metallurgy and design. Crankshafts were a weak point. “One of the early Cadillac owners involved in the forging of a set of new crankshafts (with larger journals) here in Auckland told me, you’ll never break the one in this car now.”

Another change is the shift from a cast-iron piston with rudimentary cylinder sealing to a far lighter aluminum piston with modern rings. “The more weight you can get off the piston the better, the engine picks up revs faster, improving acceleration. “A lot of these changes are necessary because of our improved roads – you can drive these cars far faster these days rather than on the muddy tracks with foot-deep ruts that they were designed for.”

This Cadillac relived a bit of New Zealand’s early history during one of the longest drives Phil has undertaken in it – a re-enactment of the 1917 Parliamentary Tour of the Winterless North, held two years ago. “The Head of the Northern Development Board, Colonel Bell, being fed up with the road conditions up north, challenged the politicians in Wellington to come and see them for themselves. “

A fleet of 34 cars was assembled, carrying 28 Members of Parliament, but it rained heavily on the tour, and they spent a lot of the time digging the cars out of the mud.” “We did the drive from Devonport to Kaitaia and back in 8 days, with two day lay-overs – it took two weeks 100 years earlier.”

The magnitude of the challenge is immediately evident as Phil invites me to settle into the comfy, deep-buttoned-upholstered passenger seat of the Cadillac and heads into East Auckland traffic. There’s plenty of tasks to keep the driver engaged – the constant monitoring of the spark-advance and throttle levers, the need to prepare to stop using the seemingly-ineffective bands mounted either side of the rear chain drive sprocket, and gauging momentum and engine load between the two planetary gears.

Although lubrication for the engine is a total loss system, Phil fortunately doesn’t have to monitor this as much as drivers and riders of many veteran machines. The Cadillac has its own way of adding engine oil required, via an engine driven pump, as it motors dramatically along, firing a couple of power strokes between each lamppost. The vast majority of Auckland motorists respond positively to the Cadillac with waves and cheers, respecting a veteran car that led the way to whatever is now their drive du jour.

However, Phil is constantly on the lookout for the odd one who doesn’t wish to wait for an old car that can cruise at 55km/h on the flat, and chug at 15km/h up hills when in low gear. Whenever more stopping power is required than the brake bands can supply, reverse gear comes into play.

The vibration of the big single is absolutely heroic, and I can only imagine what it was like before Ray replaced the heavier cast-iron piston. “I spend a lot of time tightening things up again after a run,” says Phil.

All that brass work also has a cost, not only in the elbow grease and time required, but the expense of the special Blue Magic polish that is the best restorer of the sheen of the metal. It’s all part of this Cadillac’s ability to showcase colonial motoring at its best.