1922 Essex

Words Paul Owen | Photos Tom Gasnier

When the Essex company first emerged in 1918, the ford model t held a 42 per cent share of the American market. To create its own niche, Essex decided to build a faster four-cylinder. We go for a ride in the 1922 Essex four owned by Peter and Barbara Stubbs.

According to owner, Peter Stubbs, all cars have their ‘sweet spots’ – cruising speeds where they feel at their most comfortable – and that zone occurs at 70km/h in his NZ-new 1922 Essex tourer. Sitting in the back, enjoying both the generous amount of legroom and the sound of the road rushing beneath the wooden floor, I can confirm that 70-kays is pretty much an optimal speed for the comfort of passengers too given the lack of windows in this cloth-top tourer.

Essex was purchased by the Hudson Motor Company just two years after it first started up, and would eventually become well known for its fully enclosed car bodies that it introduced during the twenties. This led one car historian to declare that ‘while Ford invented the affordable car, Essex made the enclosed car affordable’. But back when this car was packed into a box and shipped to New Zealand for re-assembly in 1923, Essex also had another unique selling point; speed.

“The Essex used to be called ‘the Fast Four’ because they could clean up just about anything else on the road at the time,” says Stubbs. “They could certainly blow a Model T into the weeds.” “Even the six-cylinder Essex models had the same top speed as the four, and lots of rival sixes of the day were absolutely topped out at 40mph.” Essex would prove its performance and durability in endurance events.

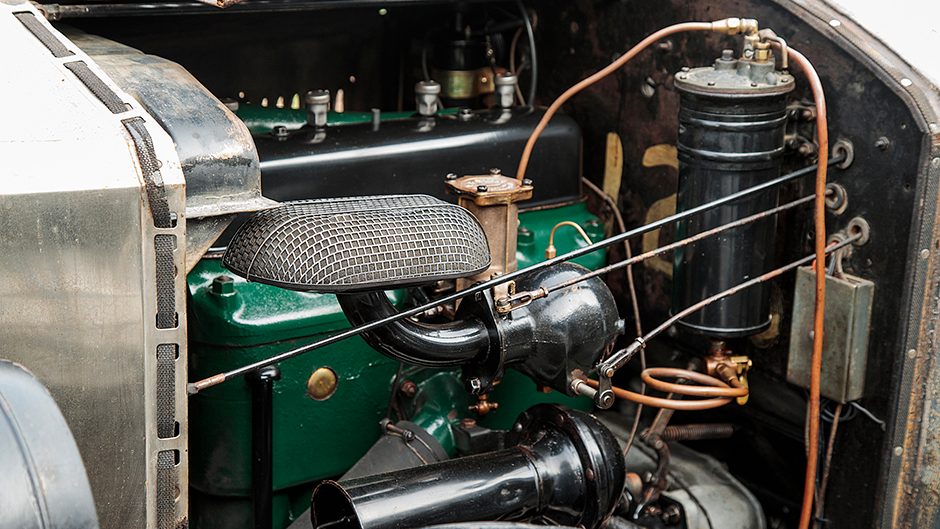

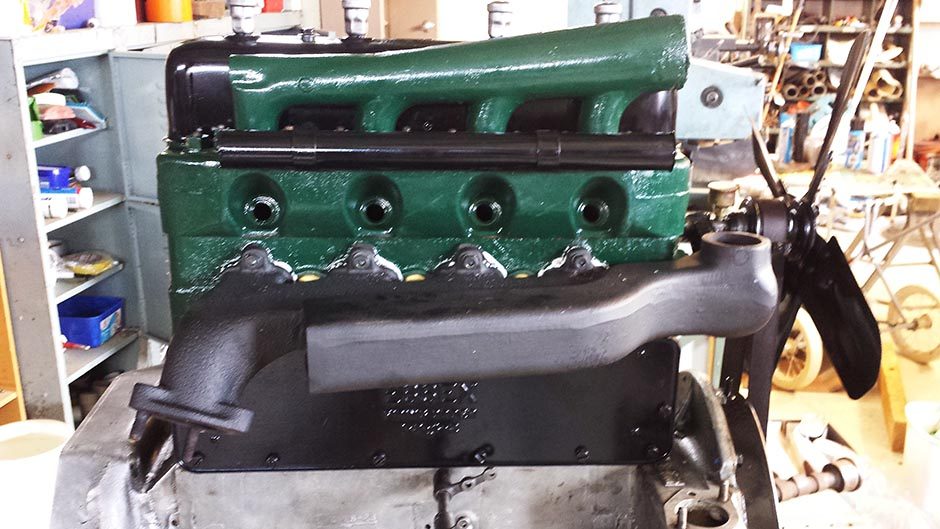

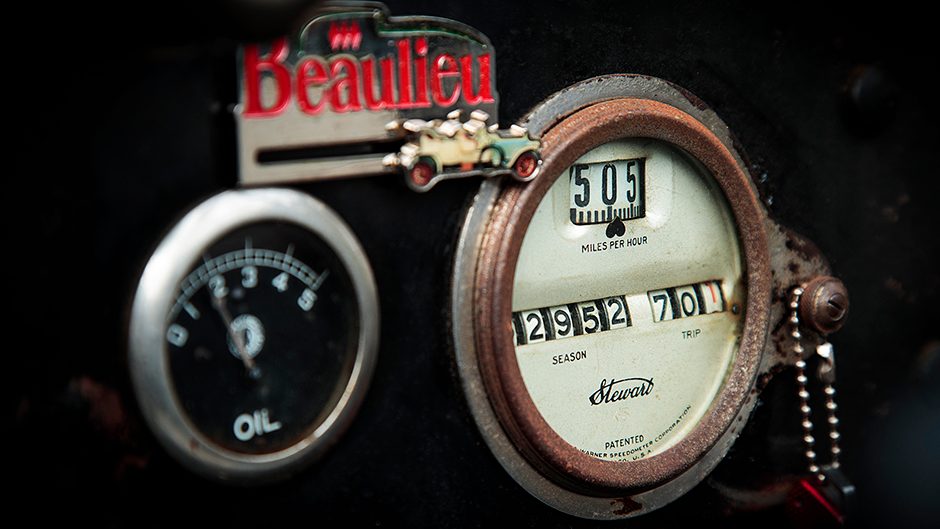

In 1919, an Essex four completed a 3000-mile durability test at an average speed of 60.75mph (almost 100km/h). In 1923, Glen Shultz used a special short-wheelbase version of the Essex four to win the Pikes Peak hillclimb. The 2.9-litre four fitted to this ‘Model A’ variant owned by the Stubbs develops 55bhp thanks to its unusual ‘F-head’ combustion chamber design (overhead inlet valve with a side-valve exhaust). That’s five more horses than the first inline sixes fitted to Essex models.

Later versions of the larger capacity Essex sixes would finally eclipse the four in peak power output, but only by three horsepower when the 58bhp Essex Super Six models emerged in 1927. Seems the one advantage that the six held over the four was its smoother running.

Meanwhile, the originality of this Essex Model A is in-the-metal proof of its mechanical sturdiness. Already owners of a couple of classic Daimlers and a big-block 1967 Oldsmobile Delta Super 88 saloon, Peter and Barbara had developed an interest in Essex cars through Barbara’s brother, Phil Kidd, an Essex fan of long standing. When Phil heard that the Southward Motor Museum was selling an Essex four in good unrestored condition, he contacted his sister and brother-in-law with the proposition that they could potentially use one of their own Essex cars in future Hudson/Essex/Terraplane Club events instead of borrowing one of his.

“We had done a couple of trips in one of Phil’s cars, and it was always in the back of our minds to own an Essex one day. “It had to be a four, and it had to be a convertible (tourer), so when this one became available it felt like something that was meant to happen.”

When Stubbs, Kidd, and body restorer, Basil Gowenlock, first picked up the car from the museum in January 2014, they quickly agreed to keep the car in its original condition while ensuring that it was structurally and mechanically sound. The car had last been registered for use on New Zealand roads in 1958, having traveled 50,033 miles since its re-assembly here in 1923.

“When I first saw the paint, I instantly said to Phil that we were leaving it ‘as is’.” The mottled finish is the result of blue paint being applied over the original brown exterior at some point in the life of the Essex. “One was water-based and the other was spirit-based. They obviously didn’t like each other.” The metal body was in relatively good condition; Gowenlock only had to replace two rusty panels at the bottom of the left hand scuttle but the wooden parts required major work. It became more of a renovation than a restoration.

“Thanks to that marvelous tool called a Renovator, we were able to cut out what was necessary and replace it with new wood appropriately shaped and glued into place.” The wooden wheels of the car also got plenty of attention. “They were sound as a bell, with no borer, but lots of loose paint. “I picked off the loose flakes with a Stanley knife, then applied four coats of Metalex, followed by a couple of coats of lacquer.” New tyres for the Essex were then imported at a cost of $700 each.

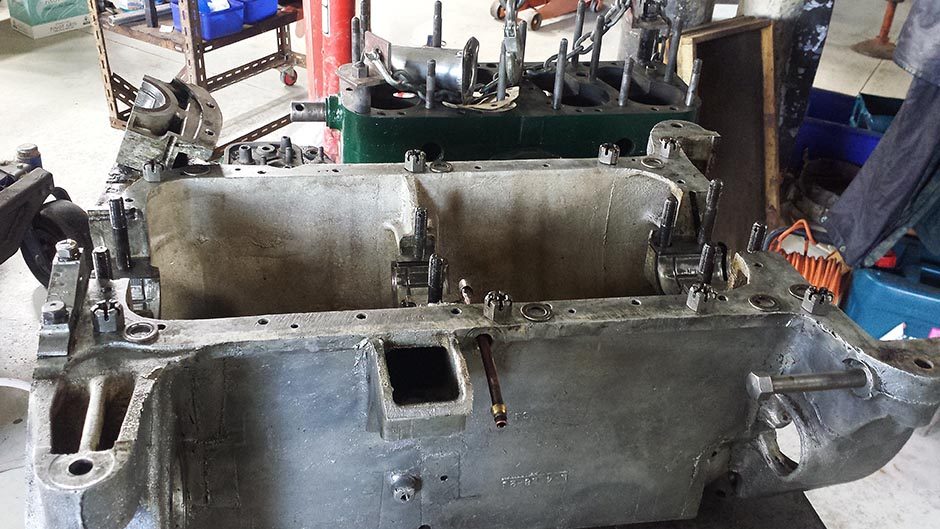

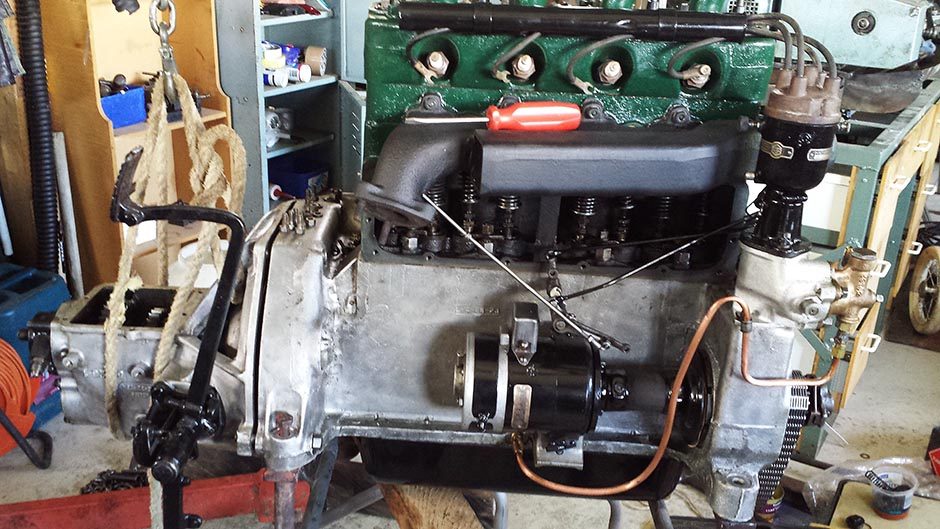

Little wonder then that Stubbs has secured the spare to the rear of the car with a padlock. Meanwhile, the Renovator was continuing to prove useful. “I could remove all the grease sitting on flat surfaces with it. “The car had been sitting around for so long that the grease preserving the chassis rails had dried out and had set like concrete.” Stripping down the three-speed manual gearbox of the Essex showed that all the bearings were fine and the clearances were checked, but the engine needed quite a bit more work.

Although the components were well preserved, years of inactivity and leaked oil had seized the working parts. It’s perhaps a testament to the combustion engine technology of the 1920s that just about all these engine parts could be resurrected, including the original spark plugs fitted to the car. “New Essex parts aren’t something you can just go out and buy.

So when something still works you tend to leave it where it is.” The only major replacement parts used in the engine were new valve springs, a new camshaft timing chain (found in Christchurch), a new camshaft spacer, new water diverter, and new oil-pickup mesh. Most were ‘liberally raided’ from Kidd’s own collection of Essex parts. Although the front end needed new kingpins and bushes, the wheel bearings proved to be in good condition.

The biggest delay in getting the Essex back on the road was sourcing replacement bearings for the rear differential. The rear drum brakes, the sole stoppers fitted to an Essex of this vintage (Essex would later become one of the first car makers to fit brakes to all wheels as well as one of the first to provide driver-informing instruments) would also cause a few headaches. “Phil knows these cars inside out,” says Kidd, “so if he hasn’t got a part, he can make one.” And that is precisely what happened with the creation of new bushes and clevis pins for the rear drums. Despite the Kiwi ingenuity, stopping quickly isn’t a strong point of this Essex. “The brakes are bloody awful,”

Stubbs reckons. While the cylindrical fuel tank of the car was rusted out and it was relatively easy to fabricate a replacement, the fuel gauge attached to the top of the fuel filler required a three-day fix. “It’s a cork on a screw that drives the gauge, and I can’t remember how many times I had to empty the tank and put another gasket in it to prevent it from leaking.” All up, the ‘renovation’ of the Essex Model A took seven months to complete, including the three days required for Nick Trethewey to fabricate a new bow for the roof structure, and sew a new hood.

Stubbs was surprised when the car got a new warrant of fitness on July 2, 2014 and the Essex could therefore be registered for the road again. “I thought the wooden doors would fail the WOF, but he (the inspector) was a really good bloke who understood cars of this era.” The Essex drives on the same number plates as it wore while at the museum, but the Stubbs have bought a set of personalised plates for it to cover the fact that those plates were only legal for a year. “Back then, you got a new set of plates every time you registered a car.”

The Stubbs call their Essex ‘JED’, in honour of its lookalike from the Beverley Hillbillies TV show – the coveted 1921 Oldsmobile Model 43 Tourer cut into a pick-up truck by Jed Clampett for his family of suddenly oil-rich millionaires. The Essex certainly attracts a lot of attention wherever it goes, says wife, Barbara. “We can be driving down the motorway and all the vehicles overtaking us in the outside lane slow down to take a better look. “Some even wind down their windows to ask ‘how old is your car?’ while still on the move. “When we go to events, it attracts an incredible amount of interest, and kids love to get in it and toot the horn.

“When we go to events, it attracts an incredible amount of interest, and kids love to get in it and toot the horn.

“I just have to tell them not to pick at the paint or slam the wooden doors first.”

For Peter, the Essex is a welcome change of pace from his Boss 290 Falcon V8 ute, his 1957 Daimler Century, and his 1965 Daimler Mk2 V8. That’s despite it returning similar fuel use figures to his 425 cubic-inch Oldsmobile behemoth; 18mpg or 15.6L/100km. Like most performance cars, the ‘fastest four’ of the early 1920s clearly has a prodigious thirst for fuel.