1958 Ford Fairlane 500 Skyliner

Words Paul Owen | Photos Tom Gasnier

Apart from various garage projects and a handful of forgotten Peugeots, the 1957 Ford Fairlane 500 Skyliner was the first car to be made with a retractable metal roof. We catch up with Steve and Bronne Panoho’s 1958 Skyliner.

To call Steve Panoho a ‘1950s Ford V8 fan’ is an understatement. By the time he met his future wife, Bronne, in 1978, he’d already owned 19 Fords from the 1950s, and had been working on them since age 11. It all started when his brother swapped a 1948 Ford V8 sedan for a 1955 Customline.

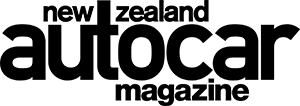

“That car really opened my eyes, and I loved the long n’ low look of the car (compared with the higher-profiled ’48 Ford). “I began to buy and sell lots of other 1950s Fords – Ranch Wagons, Mainline utes, and Customlines. By the 1980s, I had bought and sold more than 40.” So when the Panohos came across a 1950s Ford V8 that they wanted to keep, this stunning 1958 Fairlane 500 Skyliner in its original Azure Blue two-tone paint scheme, it made sense to put Bronne’s name on the ownership papers. Hence the ‘MUMZ58’ personalized plates fitted to the car, a present from their daughter.

“It’s a keeper,” says Bronne, “if it was in Steve’s name, it possibly would have been swapped for something else by now.” The seed to buy a 1958 Skyliner at some time was planted when Bronne bought Steve a Franklin Mint model of the car. Several years later, they took the opportunity to buy the real thing from a car dealer in Auckland. The deal was made more attractive by the provenance of the car.

It had been made in Ford’s Dearborn factory with the top engine option – a FE 352 cubic-inch Thunderbird Interceptor V8 that only became available in ’58 and ’59 Skyliners – then shipped directly to the US embassy in Japan. It would have become a car that transported visiting top US diplomats on their visits to the land of the rising sun.

It’s therefore highly probable that the former US Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara, had a hands-on relationship with the Panoho’s Skyliner during his regular visits to Japan between 1960 to 1968. McNamara would have instantly recognized the Skyliner as the product of the retractable-roof Fairlane project that he witnessed in the mid-1950s.

He joined Ford in 1950 as part of a team of 10 so-called ‘Whiz Kids’ hired by Henry Ford II to lead the Ford Motor Company back to the black after the company constantly posted losses in the years following World War II.

McNamara’s place in Blue Oval history is marked by his highly successful launch of the affordable Falcon range in 1959, and he became president of the company the following year. However, he gave up that business leadership at the behest of President John F. Kennedy to become the new administration’s Secretary of Defense, and went on to play central roles in the diffusing of the Cuban Missile Crisis, and the escalation of the war in Vietnam.

Prior to his starring roles on the geo-political stage, and his god-fatherhood of the Ford Falcon, McNamara was a leading manager of Ford’s Lincoln division. There, he became involved in a project led by Henry II’s little brother, William (Bill) Clay Ford, to develop the Mark II Continental. Bill Ford had become fascinated by a retractable roof mechanism developed by two engineers in Ford’s new Special Projects Division – Jim Holloway and Ben Smith.

He thought what the marketing people were calling ‘the hide-away hard-top’ would add distinction to the new Continental II. In 1953, Holloway and Smith were therefore ordered to prepare the retractable roof for production. Although the Gilbert Spear-designed Lincoln had a relatively short glasshouse, the size of the roof still posed a problem when it came to its stowage. The Special Projects team solved this by fitting a ‘flipper’ section that folds outwards at the front of the roof when it is being raised.

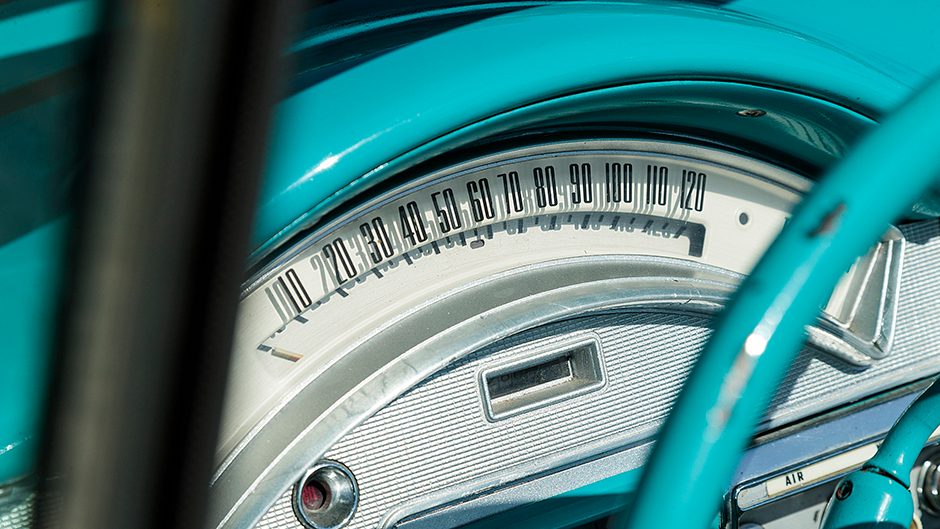

The finished design was elegant, but very complex for the time with 10 limit switches, 10 solenoids, four locking mechanisms for the roof and a further two for the trunk hood, and an additional 186 metres of wiring. The roof was fully automated and could raise and lower itself at the push of a button inside 40 seconds. Seven reversible electric motors did all the muscle work, and the enlarged battery fitted to the Lincoln XC-1500R prototype provided the juice to power them. A nice touch is the way the roof is beautifully counter-balanced during the raising and lowering operations, which allows the electric motors to be relatively small, lowering the draw on the battery.

Steve Panoho can confirm the quality of the engineering developed by the Ford Special Projects team. In the seven years Bronne has owned the Skyliner he has had just a single problem to sort when the roof wouldn’t completely stow itself away. He took the entire structure off the Fairlane and patiently traced the problem to a fault in the wiring loom.

Back in 1954, this well-sorted structure was causing quite a few headaches at Ford Motor Company boardroom level. Henry II and then Ford vice-president, Ernest R. Breech, were convinced that the Continental II was already going to have a hefty price tag, and the car couldn’t therefore afford to have that price further inflated by the cost of ‘the hide-away hard-top’.

Bill Ford countered their argument by producing the results of a marketing survey that showed Lincoln buyers were prepared to shell out an extra $2500 for a feature that allowed all the security, safety and refinement benefits of an enclosed cabin while still allowing wind-in-hair motoring upon occasion. Henry the Second and Breech were right to question the economics of building and developing the Continental II. Despite the shelving of the retractable roof, the retail price was $US10,000 when the car eventually went on sale in 1956, an incredible sum for the day.

Yet, despite the car costing the same as five Ford Customlines, Ford lost money on every Continental Mark II that it made. Ford was keen to recover the $US2.2 million that the Special Projects team had spent developing the retractable roof, and in November 1954, Holloway and Smith were dispatched to work with the engineers and designers working on the 1957 Ford range, to fully integrate the retractable roof into their model range planning.

The project got full boardroom blessing in 1955, during the same meeting where it was decided not to include the retractable roof on the new Lincoln. Unfortunately, the removable roof hadn’t been integrated into the design of the 1957 Ford range like it had with the Continental.

The design team therefore had to stretch the length of the Skyliners by 76mm to 5.35 metres to ensure that they had a long enough boot in which to stow the overhead metal. The fuel tank had to be moved from under the luggage bay floor to make way for the spare wheel. It ended up being mounted vertically immediately behind the rear bench seat, a position that definitely improved the rear collision safety of the Skyliners over all other Fords of the time.

Some of the other adaptations weren’t quite so elegant or forward-thinking, including the brutal hammering of depressions in the rear wheel wells of Skyliners as they went down the assembly line so that there’d be enough space to accommodate the roof mechanism. All up, adapting the 1957 Ford range to include the retractable roof of the Skyliner models cost Ford a further $US18 million, but at least the company could now brag that it was the first car-maker to popularise and mass-produce a folding retractable metal roof.

And it did it without the benefit of hydraulics or computers. Although Peugeot can claim to have beaten Ford in the offering of cars with a electrically-operated folding metal roofs to the public, the 1934-1940 ‘Eclipse Décapotable’ variations of various models were made in far lower numbers. As for the 1957 Ford range, it was one of the most successful in the history of the company, and became the best selling cars of the model year with 1.6 million units sold. Ford really kicked Chrysler’s butt in 1957, selling two cars to every Chrysler/Plymouth/Dodge sold. Even the much-appreciated-now 1957 Chevrolet range was humbled, the Fords outselling them by 170,000 cars.

Of those 1.6 million Fords sold in 1957, 20,766 were Skyliners bought by folk prepared to pay a 20 per cent premium above the cost of Fairlane 500 hardtop. Engine options were three V8s (272, 292, and 312 cubic inches, or 4.5, 4.8, and 5.1 litres) offering power outputs ranging from 140kW to 183kW. These came hooked up to a three-speed manual, a three-speed manual with overdrive, or a three-stage automatic.

US magazines testing the 1957 Skyliner were critical of the lack of performance, and Motor Trend found that the 183kW automatic version of the car took more than 11 seconds to reach 60mph (97km/h) from rest. It also found that the 240kg weight increase of the retractable roof made the car’s handling and braking less responsive than usual. Ford countered the critics by fitting larger-capacity V8s to the 1958 and 1959 models, the 352 cubic inch (5.8 litres) Interceptor V8 fitted to the Panoho’s Skyliner pumping out 220kW.

This did little to improve the receding sales of the cars, and Ford sold 14,713 Skyliners in 1958 and a further 12,915 in 1959. The $US3500 price tag was a big factor in this, as there was a fierce sibling rival sitting in the same showroom in the form of the far faster Thunderbird, wearing a similar price tag.

However, the real value of the Skyliner to Ford isn’t determined by the numbers of the cars sold. It’s better measured by the number of punters it bought into Ford showrooms, who’d marvel at the salesperson’s demonstration of the folding-roof trick, then plonk their hard-earned down on something inevitably cheaper and more efficient. When he became president of the company, McNamara was evidently quite prepared to keep the Skyliner going for another model year in 1960, just because of the attraction it offered to the brand.

However the semi-fastback roof design of the new 1960s Fords would have been a challenge to build in a retractable form. Steve Panoho says that there are around 1,000 Skyliners left in the world, and that most go for between $NZ70,000-$80,000.

He’s already turned down the offer of a lower North Island bach in exchange for this one, and couldn’t accept $100,000 for the car even if he wanted to. That’s because it belongs to Mrs. Panoho, and Mum sure does love her ’58.