1983 Alfa Romeo Alfasud Ti Quadrifoglio Verde

Words: Richard Opie | Photos: Richard Opie

Alfa Romeo’s Alfasud was the firm’s answer to a burgeoning small car market. The firm created a character but one with issues that earned it a bad reputation. Was it justified? We drive a minter to find out.

Lemon. It’s an automotive slur reserved for the absolute worst of the worst. But on occasion, the descriptor has been unfairly heaped upon cars that were, perhaps, simply misunderstood. One of these is the Alfasud, which heralded the rise of the front-wheel drive Alfa.

Alfa Romeo had explored the concept of a small, space-efficient front-wheel drive family car in the 1950s, culminating in the 1960 ‘Tipo 103’ concept. The 103 was a boxy sedan, featuring a dinky 896cc variant of the famous Alfa twin cam, sending drive to the front treads. It never progressed, instead Alfa focusing on the larger, rear-drive Giulia range.

As the sun began to set on the 1960s, the small car idea was revived. Southern Italy at the time was confronting serious issues with unemployment, depression and discontent. Conveniently, the Italian Government held a significant, and influential stake in Alfa Romeo. The politicians hatched a plan to create jobs by constructing a new Alfa Romeo factory at Pomigliano d’Arco, in the Naples area. From this plant would emerge arguably one of the finest front-wheel drive chassis of all time. Yet it’s also one of the most maligned, perhaps by virtue of the workforce.

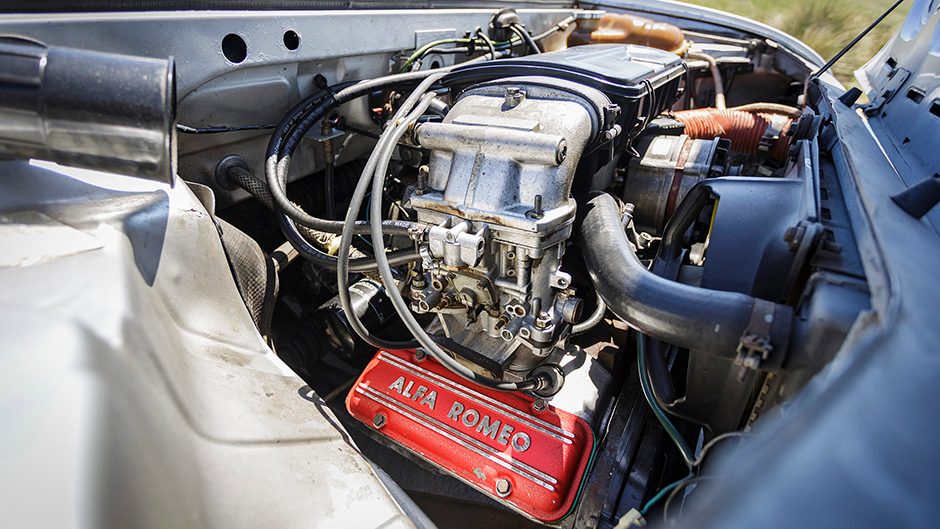

At the time, other European manufacturers were developing smaller, cheaper front-wheel drive models. Lancia’s 1.3 Fulvia, and the Audi 60 in particular piqued interest. Thus, a mandate towards a new design was given, and entrusted to one Rudolf Hruska. Hruska was presented with a clean sheet. Within the size limitations, front-wheel drive was a no brainer, and with Hruska’s previous experience with Porsche, the choice of a flat-four powerplant wasn’t surprising, especially considering the packaging requirements. The boxer engine offered a shorter overhang than a longitudinal inline four, helping with weight distribution, with the bonus of an inherent smoothness in operation.

The low engine height allowed for a lower frontal area, the slippery two-box body designed by Giorgetto Giugiaro. Macpherson struts up front with inboard front discs, and a beam axle located by a Watt’s linkage, again flanked by disc brakes comprised the chassis. By modern standards it was a simple arrangement, but one that endowed the Alfasud with characterful, entertaining dynamics.

The low engine height allowed for a lower frontal area, the slippery two-box body designed by Giorgetto Giugiaro. Macpherson struts up front with inboard front discs, and a beam axle located by a Watt’s linkage, again flanked by disc brakes comprised the chassis. By modern standards it was a simple arrangement, but one that endowed the Alfasud with characterful, entertaining dynamics.

In 1971, the public got their first glimpse of the Alfasud at the Turin Auto Show, and feedback was positive. Later that year, packing 63hp from it’s single-carb 1200cc boxer, the Alfasud hit European streets. Despite a positive reception by the motoring press for its engaging road manners, the Alfasud rapidly gained a reputation for dire quality, and hence the lemon connotations. Urban myths abound regarding substandard recycled Soviet steel being used in construction. The more plausible explanation for the unprecedented lack of quality control is likely the unskilled, unmotivated workforce. Remember this was an experiment in job creation and so the well considered design of Hruska would ultimately suffer from worker apathy.

Alfasuds gained notoriety for rusting in front of their hapless owners’ eyes. Not only that, but a plethora of electrical problems and basic build quality issues plagued the diminutive Alfa over the course of its 12-year production, a span affected by over 700 factory stoppages.

Moving forward 15 years or so after Alfasud production had ceased, this humble scribe had the opportunity to step into his own ‘sud. It explains the biased opinion somewhat; you’d struggle to convince me that the Alfasud is anything but flawed genius. Back then, the influence of a few Alfasud racers in the extended family weighed heavily on my decision.

It wasn’t a typical pick for a car-obsessed teen, especially in an era dominated by the Japanese performance revolution. But it did it all. Modified road car, track day toy, drag race weapon, camping home away from home, and daily driver. You could say the Alfasud occupies a special place in my heart.

Another driver who holds the Alfasud close to his heart is Christchurch-based Leyton Tremain, owner of this crisp 1983 Alfasud Ti “Quadrifoglio Verde” (Green Cloverleaf), the zenith of ’sud evolution.

Leyton’s fascination with the feisty front-tuggers ‘happened almost by complete accident’, he explains. “I was looking for something affordable, and a bit different and stumbled across the Alfasud.” The trip home from purchasing the car, via a set of twisties, cemented just how much fun the underrated Italian was to Leyton.

“I wouldn’t have really considered myself a driver before that,” he muses, “but it certainly accelerated that interest, making driving more enjoyable.”

That car, a Series 2 four-door served well as a daily, but a visit to Christchurch and a ride in a hotted up Ti example prompted the search for a sporty example of his own.

“One never seems to be enough,” he laughs, “but I called the seller of a car that was advertised at a price higher than the rest, even though I couldn’t really afford it.”

It was one of those rare twists of fate that works in one’s favour. The Ti checked out, having had plenty of maintenance cash lavished on it. Leyton and the seller hit it off, sorting an agreement that would eventually see the Alfasud in his shed.

So why is one never enough? Leyton explains; “The noise, they sound great! The way they drive, they’re so direct, confidence inspiring and easy to place exactly where you want. It’s also an underdog, it’s not the most desirable Alfa if you’re an ‘Alfaholic,’ and I enjoy that about it.”

But what about that reputation? The answer comes earnestly, “your relationship with a ‘sud is an involved, ongoing affair. You hear these stories of a ‘rust-free Alfasud,’ and I’d argue those people don’t know their cars well, but given the right maintenance and care you can have a lot of confidence in the cars.”

Despite the relative obscurity, Alfasuds seem to have had an impact on a lot of people. Reflecting my own experiences, Leyton recounts casual interactions with people, all of whom have had their own “Alfasud moment” at some stage. “They’ve known someone who owned one, been for a ride in one, or been surprised by one,” he grins.

For the first time in 15 years, I’ve got a set of keys emblazoned with a cross and serpent in my paws, and the Alfasud Ti is at my disposal for a blat across some fun stretches of tarmac. “Have a blast,” Leyton asserts while gesturing towards Christchurch’s Port Hills.

The memories come flooding back with the simple click of the door latch, and that whiff of 80’s Italian car that comes with settling into the driver’s seat. The driving position in these things is awkward but usable. The pedals are canted to the left and unsuitable for a size 11 pair of clogs due to their proximity to each other. Its tri-spoke wheel is comically large with a rudimentary tilt adjustment only offering slight solace.

With a flick of the key, the 1.5 fizzes into life. It possesses a unique, effervescent character, willing to rev to redline (and beyond), with an upbeat soundtrack. It’s raspy as the revs nudge clockwise, but on the overrun, oh boy, that cacophony of cheerful pops and crackles encourages a grin of maniacal proportion.

Then you go to change gear. The shift quality has never been an Alfasud strong point, more akin to digging through a bucket of icecream to find nuggets of hokey pokey. On Leyton’s example the familiar slow synchro means a hasty downshift to second is punished with audible protest, but all is forgiven as the straight road turns interesting, and some corners approach.

The Alfasud simply dances through the bends. Turn in is crisp, the front radials bite keenly as the wheel is tipped towards the apex. Lift off at pace and the rear will gently but predictably skip into the curve. Ample body roll means it feels like the ‘sud is always on tippy toes, and momentum is definitely your friend.

The boxer thrives in being worked through the gears. Get on the brakes as minimally as you can, downshift so the motor’s high in it’s rev range, hit the apex and get on it as quickly as possible. The twin Weber carbs open up responsively and play a muted inlet symphony, on the way to rinse and repeat at the next bend. It’s definitely not a fast car, but as Leyton says, drive it right and it can be a quick car.

Sure, by now they all rattle. Most have seen the business end of a welder and spray gun. Electrics are intermittent, and don’t even think about trying to breathe on some of the brittle interior plastics.

Nearly 40 years after Alfa Romeo stopped pumping these things out, can we really still call them a lemon? An amalgamation of steel, plastic and rubber that’s this much of a riot surely can’t be vilified forever? The Alfasud has more than earned its stripes. Get behind the wheel of one. We guarantee it won’t be a sour undertaking!