1995 Nissan Fairlady 300ZX

Nissan is re-stoking the zed fire with the recent reveal of the Z Proto. Here we look back on an...

In the early nineties, Japanese car-makers rolled out some pretty fearsome machinery. Honda unleashed arguably Japan’s first supercar in the mid-engined NSX, Mazda turned the RX-7 into a serious Porsche-killer, and Nissan and Mitsubishi produced their interpretations on the continental GT with the 300 ZX and the GTO.

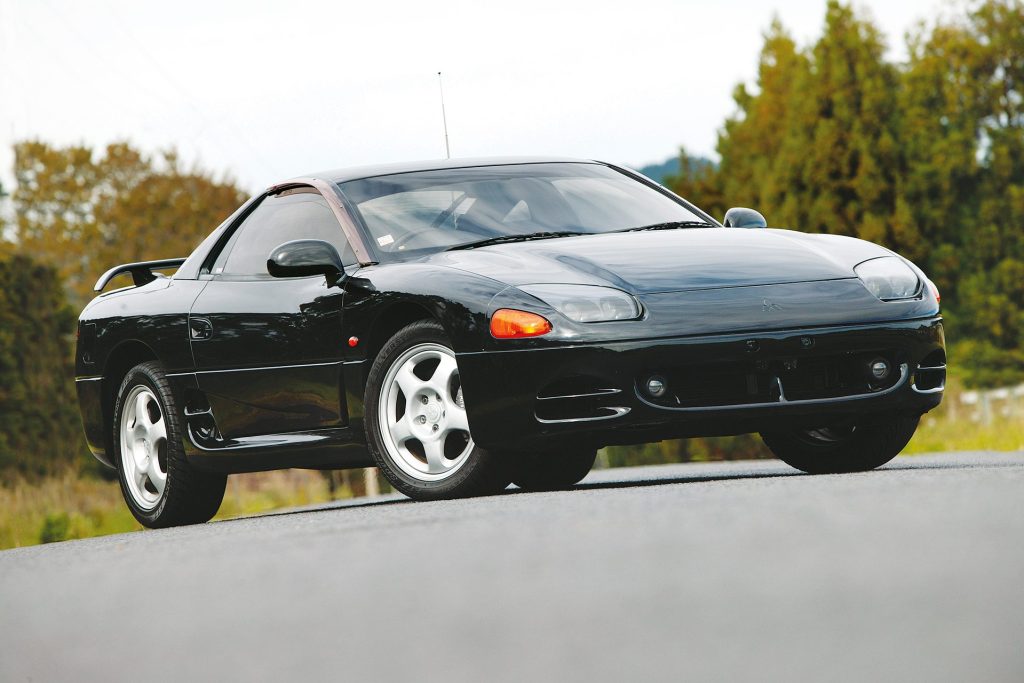

Mitsubishi’s GTO was a car that was compromised from its outset. Although it had wanted to build an out-and-out sports car, Mitsubishi had bowed to the needs of marketing and economics. The GTO was to be shared with its US partner, Chrysler, as a cheap sports car, dubbed the Dodge Stealth, and to meet those commitments, the car would be based on the front-drive Eclipse platform and would just have to make do. All very well, but to handle the turbo power Mitsubishi had planned, they would need to sling a rear driveshaft and a diff out the back to get all the power down.

It was unveiled to the world in 1991, complete with twin turbochargers and a host of electronic gimmicks. The base GTO was powered by a 3.0 litre V6 with either a four-speed auto or a five-speed manual. Despite offering up a respectable enough 165 kW and 277 Nm, the overall performance of the GTO was hampered by the excessive burden of its driveline. Weighing in at 1750 kgs, the GTO is a porky beast, and in normally aspirated form can only manage a 0-100-km/h time in the high eight-second bracket. For it to be a car with any sporting aspirations, Mitsubishi had to add some mumbo.

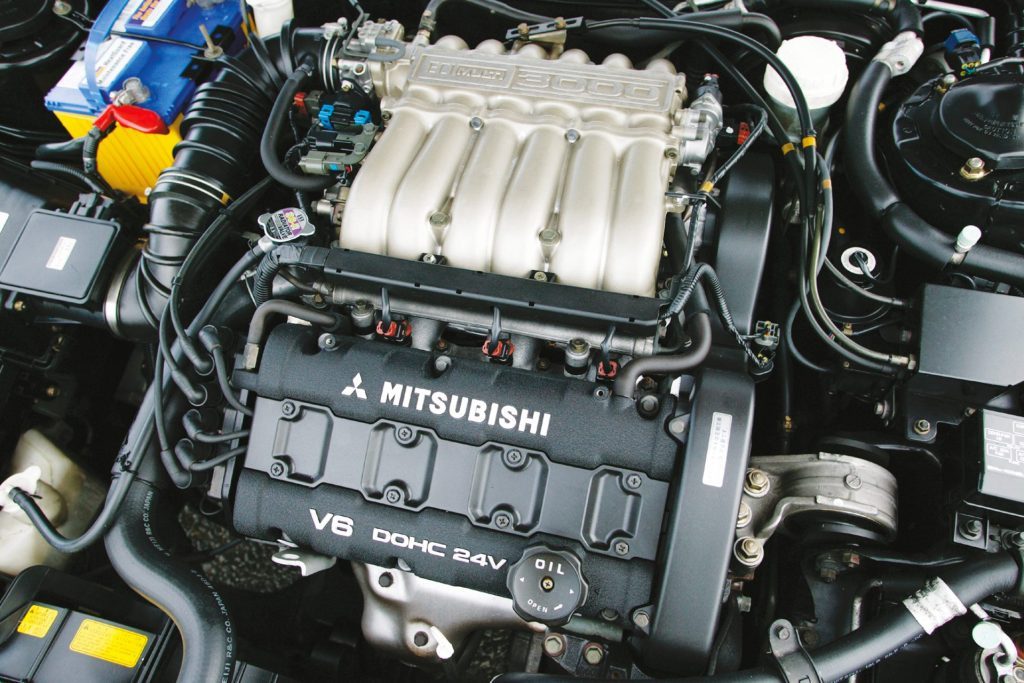

The engine, an iron block 60 degree V6 with aluminium four-valve heads, was treated to two of Mitsubishi’s TD-04 turbochargers. The engine produces a lot of torque from down low, and hits its peak of 398 Nm at 4500 rpm, with as much as 300 Nm at just 2500 rpm. To help achieve this, Mitsubishi used a low-friction valvetrain employing needle-bearing roller rocker arms, which activate using half the torque of the conventional design. The engine, with forged conrods and steel-reinforced aluminium pistons, runs a compression ratio of 8:1. Stock standard, the engine was helped along by 9.7 psi of boost and produced the Japanese maximum of 205 kW at 6000 rpm.

The turbo was only available in five-speed manual form until 1996 when a sixth gear was added. Drive is transferred via a centre viscous coupling diff, and under normal driving, splits the torque 45 per cent to the front with the rest going rearward. When things get crazy, it can transfer more torque front or rear via this mechanism.

Mitsubishi went all out and included speed-sensitive four-wheel steering in the whiz-bang model. This means that after monitoring the speed, steering angle and the lateral force being exerted on the toe control member of the rear suspension, the car will allow the rear wheels to be turned up to 1.5 degrees in the same direction as the front wheels.

In later models the aerodynamics went active. Above 80 km/h the front air dam lowers an additional eight centimetres, while the attack angle on the rear wing increases by 15 degrees, both retracting back when speeds dip back below 50 km/h.

The shock absorbers have an electronic adjustment with the driver being able to choose between a softer touring mode and a firmed-up sport mode. The 17-inch alloys allowed for big, 310-mm rotors up front and 295-mm items at the rear, acted on by four-pot calipers all round with two-channel ABS.

Inside, the GTO’s spec matches its technical prowess. Leather-clad seating is electrically operated and the side bolstering of the driver’ seat can be adjusted to fit your torso. The rear seats are hopelessly cramped and the shallow boot offers little space also. But it has a great spec for its time: wheel-mounted audio controls, dual airbags and power everything.

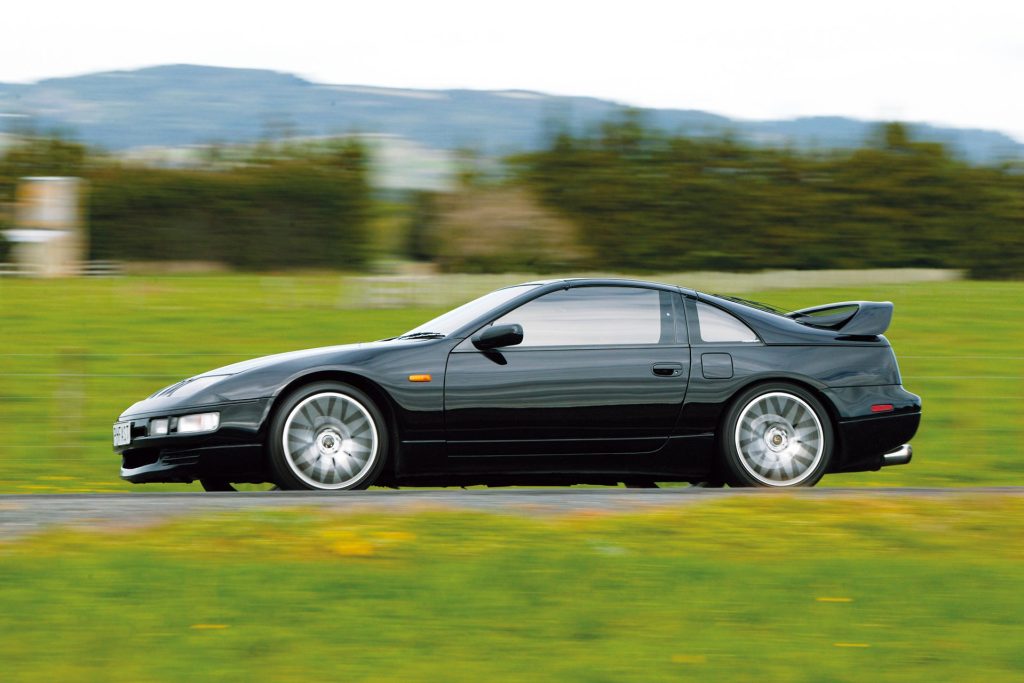

The car that the GTO was to square off against was Nissan’s 300 ZX. Unlike the GTO, the ZX is from a pedigree, having a direct lineage back to the great 240 Z of the 1970s. The car evolved gradually, growing in size and engine displacement, and with the 280 ZX, Nissan adopted the subtle art of turbocharging. The first 300 ZX, coded Z31, was a squared-off, curvy design that was an ugly son of a Z-car – yet another styling disaster from the ’80s. With that atrocious decade behind them, Nissan rolled out the Z32 300 ZX, a completely new design that was shorter in length overall but with an increased wheelbase. With a rear-wheel-drive platform, the engineers were able to produce a more focused sports car than the GTO. Nissan worked hard at producing a stiffer monocoque, and that gave the suspension boys a better platform from which to work. Nissan developed a set-up that would react differently, depending on the demands. By using a trick, linked king-pin mechanism on each wheel, the suspension can sort out the separate functions of camber, caster, steering offset and antiroll. One of the effects of this can be seen when the car is pitched into a bend: the offset suspension arms act to crank in more camber to increase the contact patch of the tyre.

Add in Nissan’s Super HICAS four-wheel steering and it was a very sophisticated business. Not to be outdone on the techno front, Nissan used speed-sensitive steering, which decreased the assistance at speed by limiting the fluid flow to the hydraulic system, and added shock absorbers that could be adjusted via controls in the cockpit.

The jewel in the crown was the engine with its twin turbos and variable valve timing. It used the old 3.0 litre V6 from the Z31 but included new, alloy, four-valve heads with double overhead cams. To achieve high revs for peak power figures but maintain low-down torque, Nissan’s NVCS (variable valve timing) was used to reduce valve overlap at light loads, greatly improving the engine’s drivability. Providing the puff are twin Garrett T2/T25 hybrid turbos, which act in unison on each bank of cylinders rather than sequentially.

Weight saving was a concern of the engineers, and some of the components in the suspension and body are made from aluminium, including the brake calipers. The 16-inch wheels were deemed enough back in the nineties and, in a weird set-up, Nissan went with 279-mm discs on the front and placed larger (297-mm) discs on the rear. Up front it has four-pot calipers but makes do with two-pot items rear, while ABS prevents lock up.

The 300 ZX turbo comes in either two-seater or 2+2 form, has an automatic option, and can come with a targa roof.

Inside, it’s similar to the GTO with power everything, AC, cruise, etc.; but no airbags, though leather was an option.

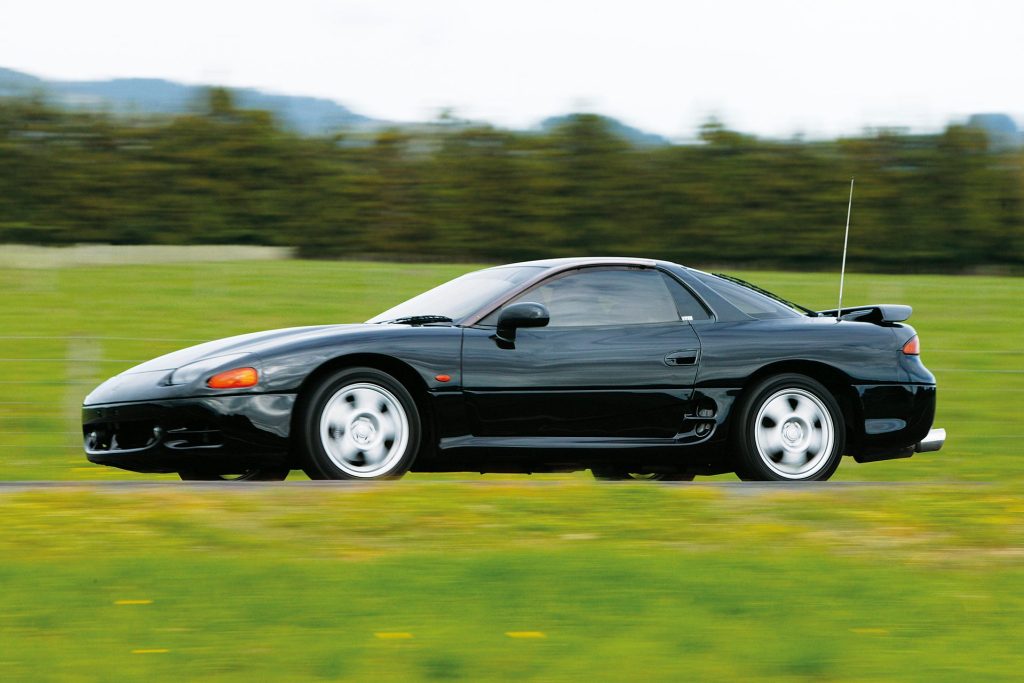

The cars were very trick back when they were new and came with a hefty price tag. At launch, a 300 ZX turbo would have set you back almost $100,000, and if you could have purchased the few GTO’s imported new, they would’ve cost $75,000. But now, some 13 years down the track, they still offer all the go for substantially less dough. The trick nowadays is to track one down. We had trouble sourcing a twin-turbo GTO – hence the 3.0-litre in the photos – and were extremely lucky to find one of the rare two-seater twin-turbo ZXs. Aaron Vrhovnik’s great-looking 1991 300 ZX had undergone a few minor mods in its time with a previous owner, mainly a race spec ECU, which, among other things, had raised the boost lifting it to around 12 psi. The 1996 face-lifted GTO had 135,000 km under its belt and a sticker price of $16,995. Both of these über coupés can be had from as little as $10,000 for a normally aspirated version, while you could still expect to pay up to $25,000 for a late-model turbo with low mileage.

The 300 ZX was still a powerhouse after 134,000 km. Helping me do the assessments was Aaron, a keen 300 ZX club member, and he was keen to see how his car would do with the VBOX strapped on – and promptly reeled off a 0-100 time of 6.1 seconds while trying to keep tyre smoke to a minimum. In the 80-120 sprint, it was good for a 3.77-second burst, and it stopped in 39.83 metres from 100 km/h. Not bad for a 13-year-old car, but the clutch was complaining after a few hot runs. The GTO twin turbo has factory-quoted figures of 5.5 seconds to the ton – and no doubt the traction off the line would be its key to such a claim. The ZX was still a nimble handler, getting plenty of drive off the corners and offering substantial overtaking ability. While not quite offering the driving experience of the sensational 350 Z, the old ZX was still faster in a straight line. The steering was well weighted and free of understeer, but with the large tyres, was keen to follow the bumps of the road. Power oversteer was easy to provoke, but not hard to manage. The driving position was great, hunkered down low, but the gear lever was too far away with long throws.

Although the GTO was lacking the power, it still had some sporting abilities, with responsive steering and loads of grip in fast sweeping corners, but ultimately, its substantial weight dulled the experience. The GTO was unable to disguise its size, and was a lot less chuckable and fun than the ZX. If any car was in need of turbo motivation, it’s this one. Lacking any urge to pull out of tight corners and with a tendency to plough when you’re running hot, the normally aspirated GTO is a flawed sports car. The GTO was better to live with inside, however, with a bigger cabin and a superior driving position.

Owning a used Japanese supercar shouldn’t be entered into lightly. Remember, they’ve all had a good seeing to, and with the masses of complex gadgetry on board, there’s lots that can go wrong. Both cars are bristling with sensors, and if they are faulty, the car will – predictably – play up. For example the 300 ZX has knock sensors, which, if corroded, will result in a reduction in the boost. They are simple to fix but hard to diagnose, so find a knowledgeable mechanic.

ZX’s run hot, which is fine, but makes cooling-system maintenance a must. Most engine failure in these cars is a result of overheating due to a failure in the coolant system. GTO gearboxes, as in all Mitsubishis, are a weak link. Syncs can go and the 4wd system doesn’t handle substantial power increases well. Detonation is something to watch for in both cars and both will run better on higher-octane fuel. The Nissan drivetrain is super tough and well capable of handling higher outputs without bother. If buying from a dealer, a warranty will save tears.

Both these cars represent good sporting buys in turbo form, and at a price most can afford. The 300 ZX offers the more sporting option, with rear-wheel-drive fun and a great suspension set-up that will always have you taking the long way to the dairy. Great to drive and pleasant on the eye, the ZX has it over the GTO in the two areas that make it a better sports car.

This article was originally published in the June 2003 issue of NZ Autocar Magazine.

You may also like…

Nissan is re-stoking the zed fire with the recent reveal of the Z Proto. Here we look back on an...

Toyota’s answer for someone craving a sporty GT in the 1990s was the Z30 Soarer. We take the wheel of...