1992 BMW 318is BTCC

Words/Photos: Richard Opie

When Group A met its demise, 2.0-litre super tourers needed to step up and offer a spectacle. In 1992, the British Touring Car Championship finale gave the punters just that. An integral part of it all was this uniquely green E36 coupe.

Sweeping the silverware at the conclusion of a tough-fought season is no mean feat. When we’re talking about the 1992 British Touring Car Championship (BTCC) winning BMW E36 though, the yarn behind this teal-coated tin-top extends well beyond its title credentials. Much of the story is now etched into touring car folklore. From murky criminal dealings, to a controversial conclusion to a tough season, the history of VLM E36-001 is a colourful one. And it’s still writing chapters as it competes in New Zealand’s incredible and varied Historic Touring Car (HTC) group.

As the 1990s dawned, the sun was setting over the Group A touring car era and entry lists were on the wane. As such, in 1990, the BTCC grid comprised a couple of groups. Class A consisted solely of Sierra RS500s, while Class B involved a more eclectic bunch of cars, all fitted with 2.0-litre naturally-aspirated engines, a sign of BTCC’s future. One of these Class B competitors would be Vic Lee Motorsport (VLM), a team captained by it’s eponymous figurehead, campaigning a single BMW E30 M3 for driver Jeff Allam. For a fresh team, the performance was a relative success. Allam wound up sixth overall and third in Class B, which would set the scene for the following year. For 1991, VLM and Will Hoy would triumph in the championship, laying the foundation for a watershed 1992 season for both the VLM team, and the BTCC. Late in 1991, VLM took delivery of a trio of fresh BMW Motorsport shells. As the story goes, BMW had initially developed the two-door E36 shell as a base for Group A competition. However, with Group A dead and buried, the E36s ended up in the BTCC, as 2.0-litre machines campaigned by Prodrive and VLM.

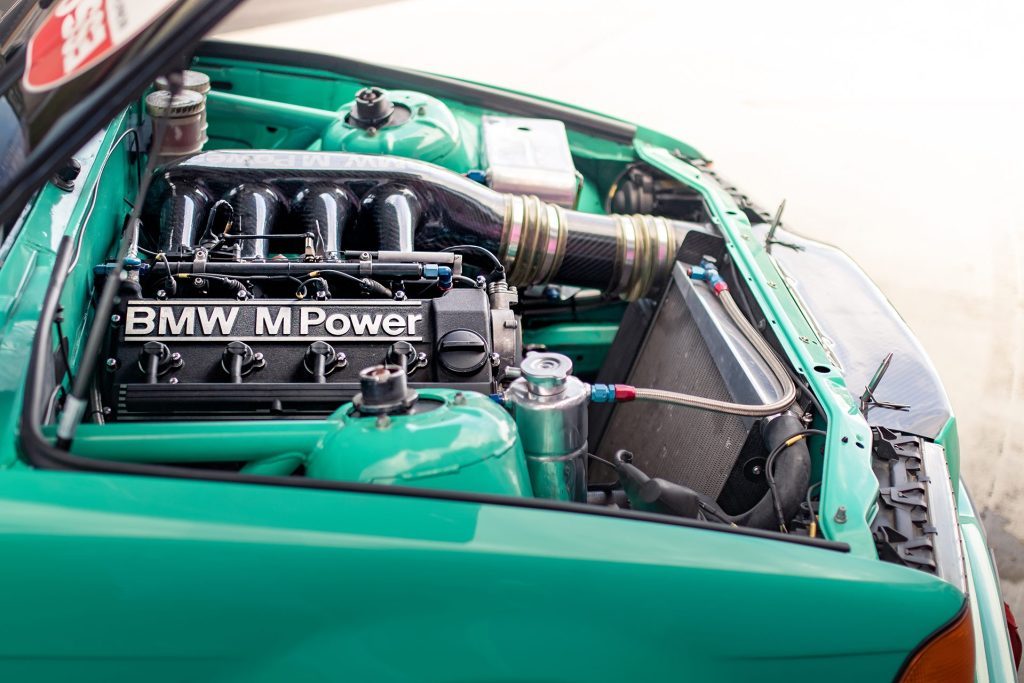

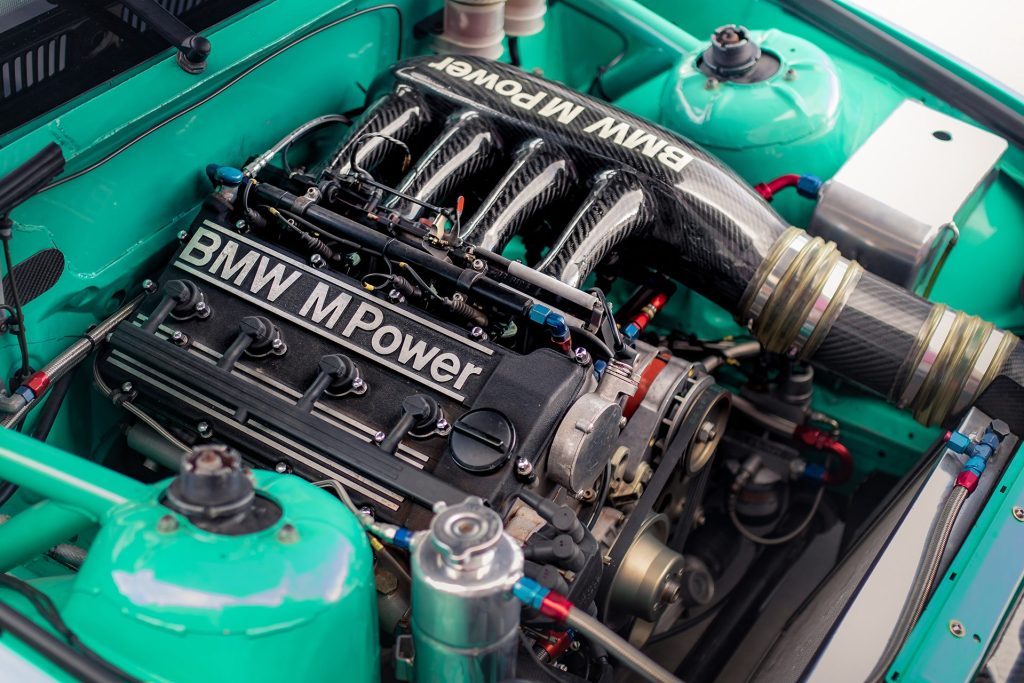

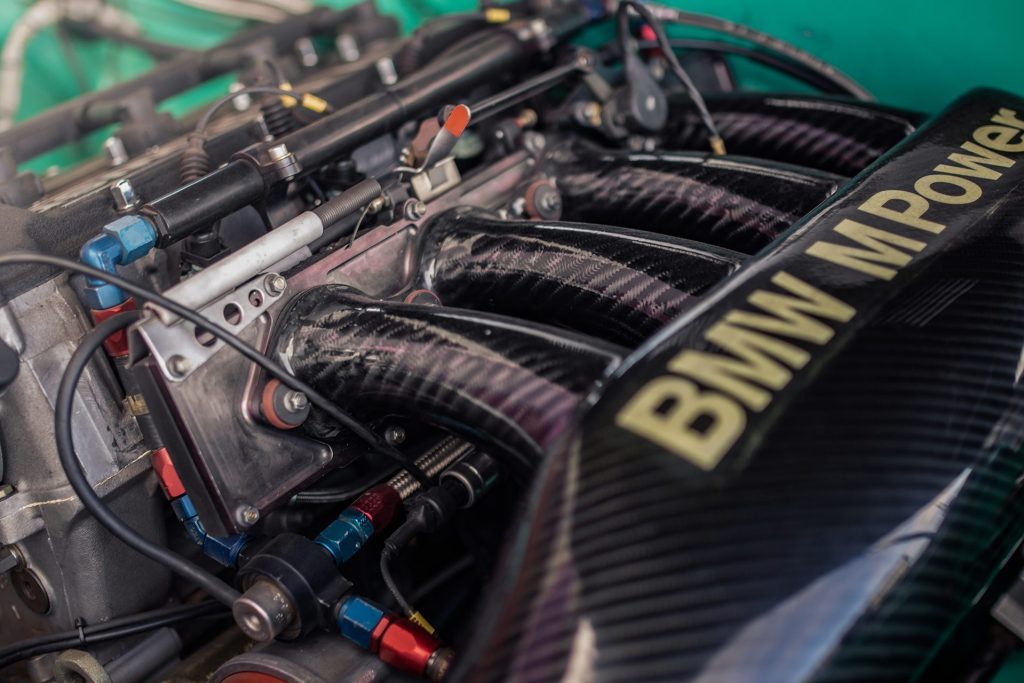

The VLM recipe was reasonably straightforward. For the powerplant, the E36 utilised the S14 four-cylinder of the Group A M3s, downsized in capacity and equipped with a dry sump oiling set-up. Good for about 260hp, the smaller mill was mated to a six-speed Holinger sequential, sending drive to the trailing-arm E36 rear end. The Holinger was an unusual choice, with special lightweight ‘boxes supplied directly to VLM. A particular innovation was the car’s bespoke ABS system, a first for touring cars and believed to be of particular benefit in the often-damp English race conditions.

The combination of the 18-inch wheels and low ride height is critical to the super touring aesthetic, even in these early incarnations, but while the bodywork appears ‘stock,’ according to current custodian and restorer Warren Good, it’s anything but.

“They got pretty radical with the bodies,” claims Good. “When they arrived at Vic’s they were totally dismantled and tweaked, they spent something like £290,000 on each of these, so they were far from stock. To keep weight down, they often didn’t even run a wiper motor, and there’s no window mechanism to speak of in the doors.”

Those tweaked shells were clothed in a unique shade of teal, allegedly the result of combining all the primary colours of the competitors’ cars into one pot and working with the result. It’s not exactly cohesive, but it sure is iconic. The inclusion of sponsor Listerine’s mascot ‘Clifford the Dragon’ on the bonnet also made the livery a hit with kids.

The ’92 season began in an unremarkable fashion. The cars were fresh, and slim on chassis development, with rear suspension woes causing a patchy start. It’d take half a season for the BMWs to come on song. Tim Harvey, at the wheel of VLM E36-001, would stand atop of the podium at Donnington, which would herald a charge to the end of the season, duking it out with Vauxhall’s John Cleland, and Toyota’s Will Hoy.

It would all come to head at the very final round. But not before another matter surfaced, adding further colour to the already brash hue of the VLM machines. Sitting in a hotel following the Brands Hatch round, Vic Lee was immersed in conversation with high ranking BMW personnel. Le topic du jour? Inking a deal to run the factory BMW team in the BTCC. However, when the police entered the room, Vic then reputedly uttering “I don’t think this deal’s going to go any further,” completely aware of why they’d been interrupted.

As it transpired, the VLM team’s regular testing at Zandvoort in Holland had raised a few eyebrows. As part of ‘operation Bounce,’ police and customs officials stopped the VLM transporter on a trip back from testing, discovering 40 kilograms of cocaine stashed in the trailer. Lee was arrested and the season was almost dashed for the VLM outfit, with both BMW Germany and Shell poised to withdraw their backing. An 11th-hour save by Ray Bellm and Steve Neal, who effectively bought the assets and founded what is now known as Team Dynamics, enabled the outfit to fight until the end of the season, leading to one of the most iconic moments in a touring car race, ever.

Heading towards the final round at Silverstone, Harvey crashed during testing and caused serious, but not insurmountable damage. The call was made to switch cars with teammate Steve Soper, as Harvey required a fighting-fit steed. Harvey was leading the championship by a solitary point over Cleland, with Hoy a few points back but still in title contention. As the green lights faded and the field set off for the championship decider, initial contact between Soper and Vauxhall’s David Leslie caused the BMW to spin, and then Peugeot’s Rob Gravett collected Soper, which would see the BMW pilot shuffled to the back of the pack.

Despite heavy damage, Soper charged through the pack with blistering pace, and was up to seventh place, tailing the three championship contenders. Fourth to seventh would include Hoy, Harvey, John Cleland and Soper. Harvey made an attack on Hoy at Copse corner, running them both wide, allowing Cleland and Soper through.

Soper would soon overtake Cleland, putting the Vauxhall in a BMW sandwich, and from there things would start to take a chaotic turn. Harvey would make it past Cleland, which prompted Soper to let his team mate past and act as a de facto ‘blocker,’ making life as difficult as possible for Cleland. Cleland would divebomb Soper on the inside heading into Brooklands, with Soper slamming the door and the two cars contacting, the Vauxhall thumping the kerb and flying onto two wheels. Despite this the Vauxhall moved half a car length in front of the BMW, en route to Luffield corner. But Soper took no prisoners. With half of his BMW on the grass he took to the inside, the net result being heavy contact with Cleland that sent both cars spinning into the barriers. To this day, the imagery is iconic, Cleland seething with rage upon exiting his stricken Vauxhall and then uttering the famous line “the man’s an animal,” in reference to Soper’s highly controversial move that cost Cleland the title.

It’s a moment that was captured from every possible angle and beamed worldwide. Despite the controversy, the incident was one that almost single handedly revitalised the BTCC, portraying a no-holds-barred motorsport competition to the mainstream and arguably attracting plenty of new fans who were hungry for the sort of argy-bargy on-track rivalry that would come to epitomise the championship. And the BMW E36, chassis VLM E36-001, was integral to it all.

So how does such an icon of English motorsport end up on Kiwi shores? Following the 1992 season, the E36 shell was effectively barred from racing, as the rules evolved to encompass only four-door saloons. Its ABS system was also banned, but VLM E36-001 continued its race career, albeit briefly. The car ran a single French championship round in 1994, having been sold, before being mothballed and eventually ending up in Norway. There it is was rebuilt as a bit of a ‘hot rod’ with a 2.7-litre version of the S14 engine and an XTrac transmission. Eventually, courtesy of Kiwi race car philanthropist, Rick Michels, the car would end up in New Zealand, before being acquired by Good – a self-described BMW nutter – with a restoration beginning in 2013.

“It was pretty good to start with,” says Good, “the main structure was in great condition, but they’d added flared arches, aero, things like that. It was the biggest thing to deal with really, but the internals like the dash, inner guards, roll cage, even the original door cards were still with it.”

The shell received a thorough refresh, including a new application of teal paint.

“We had to source a new engine. They never actually produced a 2.0-litre version of the S14 and so there were various ways the different teams did it.” Regardless, a new dry-sumped 2.0-litre was built, and mated to a brand spankers Holinger six-speed, in the pursuit of correctness. And correct, it is, with the car presenting beautifully, resplendent in its original livery. Good’s even had the fortune of meeting the car’s original engineer, Glen Jarret, who incidentally happens to be a Kiwi, offering loads of information on car set-up, as well as original drawings and blueprints.

With plenty of seat time in a Group A BMW M3 (that he still owns), Good’s well placed to make a comparison between the two eras. “The super tourer is a lot harder to drive because the smaller engine has such a narrow powerband. You’re running through the gearbox all the time, and the Holinger isn’t an easy thing to shift.” Nonetheless, he explains, he gets a great deal of pleasure from the drive, not to mention the attention the car receives.

He’s even been back to England with it, running Brands Hatch and Silverstone historic events with a troupe of fellow Kiwi touring car drivers. “They said we’d need to rope the car off in the pits before we went, and they were right,” laughs Good. “We were absolutely mobbed by people wanting to see the car, talk about it, even try to touch it as we drove out from the pits. People couldn’t believe we were taking it back to New Zealand while we were loading the container,” explains Good.

But how good is it, having such a legendary piece of motorsport history turning laps on Kiwi soil? For all of it’s relatively modest looks, the BMW is undoubtedly one of the most important of its ilk, a machine that packed competition, controversy and intrigue all into one race season.