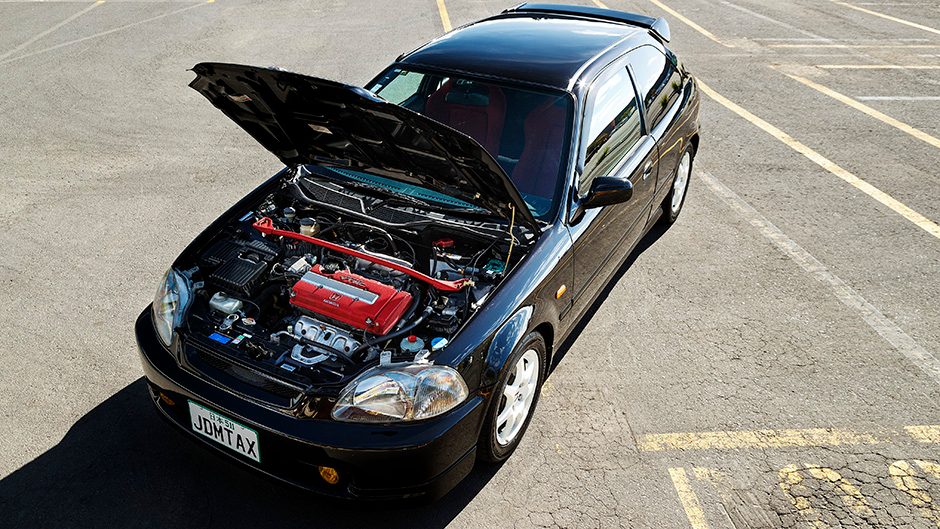

1997 Honda Civic Type R

Words Kyle Cassidy | Photos Tom Gasnier

Life begins at 6000rpm for the Civic Type R. That’s when the engine’s high-lift cam profile takes over and all hell breaks loose. We drive a well-kept example of the first-generation Civic R.

Your starter for ten this month – which Honda model debuted the firm’s VTEC (variable valve timing and lift electronic control) system? Nah, not the NSX, but rather the 1989 Integra XSi. Its 1.6-litre B16A twin-cam engine made the magic 100 horses per litre thanks to its trick camshaft arrangement that let it rev like mad. At easy engine speeds, it was all docile and demure to aid drivability and save gas. But at higher revs, when the driver wanted more go, the VTEC system switched to a different camshaft profile which not only altered the timing but also the lift and opening duration of the valves. With more air able to get in and out, it revved harder and made more power, 160hp at 7600rpm to be exact. It would feature in other models too, like the CR-X Si and Civic SiR, and provided the starting point for the unit in Honda’s third Type R offering, the 1997 EK9 Civic Type R.

According to Honda ‘the Civic Type R was developed in the spirit of pure racing to provide the customer with the utmost in driving pleasure’. The engine, the B16B, retained its 1.6-litre capacity but made 185ps (182hp or 136kW) at a rip snorting 8200rpm with a 9000rpm redline. Torque was a modest 160Nm wound out at 7500rpm. The engine featured a re-developed valvetrain allowing for the high engine speeds, reduced internal friction, improved breathing, a higher compression ratio and a strengthened block.

To aid dynamics, the EK generation three-door Civic was treated to a partially seam-welded shell, and chassis braces were added. The suspension was tuned and lowered, and bigger brakes fitted with revised ABS settings. This was the lone driver aid, save for the fitment of a torque-sensitive helical LSD. It gained R-specific wheels with a five-lug stud pattern and these came wrapped in Potenza RE010s, Bridgestone’s premier tyre at the time.

The R treatment of the interior saw Recaro buckets added, a revised pedal layout for easier heel and toe procedures, a Momo steering wheel and a short-shift gear lever for the five-speed manual. That was topped with a titanium knob.

Honda made just over 16,000 of the EK9 with production ending in early 2000. This starlight black pearl R is owned by Aucklander, Hayden Johnson. He’s had it for a few years now, having stumbled upon on it while at an auction in Japan. “I bought this in 2018. I’d been looking for one forever. I’ve had a lot of Hondas and always wanted an EK9. I really wanted a Phoenix Yellow one, but they are rare and, for whatever reason, they are the ones that seem to get played with the most.” Hayden was ultimately after an unmolested car.

“This car has done 220,000km, but you wouldn’t know it. I checked the auction sheets when I was up in Japan, and I saw the kays and its 3.5 grading and thought it would have been an absolute animal, so I blanked it. I just happened to be walking around to check some other cars and I saw it. It was sitting right at the front of the row, and I thought wow, what’s that one? I had to check it out, and then realised it was the one that had done 220 kays. And to find a car in such an original condition, I just had to own it. The boys thought I was crazy buying it but it was the right car.”

Despite the high kays, Hayden says he hasn’t needed to do anything to it. “It’s as it was on the day. It’s had a once over from the boys at Final Touch, but it’s had no paint work, nothing. It was a one-owner car. It’s been someone’s baby. They’ve used it but not abused it. It is absolutely how it left the factory. A lot of this stuff has been on track, or been modified so to find a clean, tidy, unmolested example is so hard now.”

Hayden also has a DC2 Integra R, and owned most of Honda’s front-wheel drive performance machines, along with a few race cars including an ex-Spoon Sport S2000, used in the Endurance championship.

But he rates the EK9. “Everything after these lost that pure Honda-ness. They went to the i-Vtec engine and the K20 is a good motor but it’s very different to these where you have that brutal onset of the VTEC. These are like race cars for the road.”

Hayden says after he crashed an Integra R, he ended up transferring its powertrain into his EK race car. “The same gear in the Civic made it two seconds a lap faster than the Integra.” He says his EK9 is one of the more balanced cars he’s ever driven. “There is a bit of power off oversteer which is quite interesting for a front-drive car, but you just get back on the gas and it pulls itself right again. It’s a forgiving car to drive and it’s pretty fast for what it is.”

And that’s what we discovered when he flicked us the keys. There’s really only one way to drive the Type R, and that’s like you stole it. The VTEC needs to be on cam to deliver, meaning at least 6000rpm, which is about where most modern performance hatches start signing off. The B16B sounds right angry as the mechanicals start lashing in a frenzy and the induction is amplified as the engine sucks in more air per revolution. The four-pot kicks on, the tacho needle swinging into the red past 8400rpm, which is the best time to grab another gear. Short shift at say seven-five, and you’ll dip down below 6000rpm, where it feels genuinely lethargic. The ratios could do with being more closely stacked but nail it right with a quick shift and the revs fall neatly to 6000rpm so you can keep attacking. The frenzied power delivery requires a dedicated commitment to every corner. It’s not really a car to go bananas in along unfamiliar territory as you need to be on it, always. But it’s a gem of a thing on a well traversed path.

Despite the age and kays this has travelled, it still feels youthful. It rides low and firm but there is enough yield in the suspension to deal with the bumps. There’s lots of road-related din and suspension noise and you know everything about the road surface below. The steering is alive, the wheel zinging in your hands and, being so light, the R turns easily. For a front driver with not much hanging out back, this feels unnaturally well balanced. There’s some power-on understeer to contain and occasionally the rear gets light. Interestingly this doesn’t upset things but rather neutralises the cornering line, the rear helping right the front so you can keep the power on, which we know is key. There’s some tramlining but no torque steer as the LSD pulls it well out of the bends so you can give it death right off the exit. Get hard on the brakes and that chassis balance doesn’t disappear – it’s stable for such a small car – enabling it to turn in on command. The pedals allow for easy throttle blipping, the ’box a slick little number so everything gels nicely. And given the engine isn’t big on power, the controls are light, as is the entire package, so there’s no effort to get it slowed up and turned in. Whipping the engine so mercilessly feels mean for a car of such age and mileage, but it doesn’t work otherwise, and it does feel like it would do it all day long.

For Hayden, it’s a weekend car at best now. “I’ve got a bit of this JDM stuff that I’ve been collecting because I’ve seen what has been happening to the prices, and where I’ve been able to, I’ve jumped on certain stuff and held on to it. I’ve got friends that buy shares, others buy bitcoin, but this is my investment, and it’s something you can enjoy at the same time.”