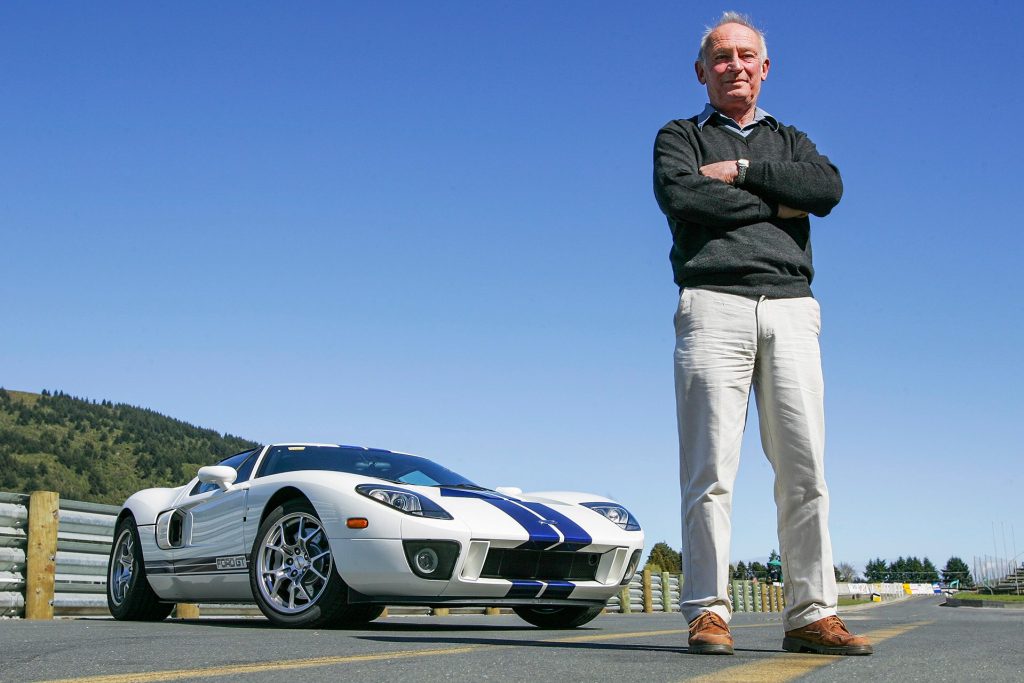

The smile on Chris Amon’s face says it all. The man who steered a Ford GT40 to arguably the most famous Le Mans 24-hour endurance race victory of all time is beaming like a lottery winner. He’s just driven Peter Walton’s left-hook Ford GT for several brisk laps of Taupo race circuit. While Taupo in no way resembles the iconic Le Sarthe circuit where the world’s most important 24-hour motorsport event is held, the GT looks just like a carbon copy of its legendary ancestor. And Amon looks more like the fresh-faced racer of 40 years ago than I’ve ever seen him. His eyes sparkle with enthusiasm as he articulates his first impressions of the GT:

“This is pretty much how I remember the original in terms of the way it drives. It feels like they used to be in terms of balance, but it is a lot more refined.

“It is sprung a bit softer, although the GT40 was soft as well. We had three to four inches of wheel travel back then, and the race car had the supple suspension of the [pre-downforce] era. I think Formula One would be a better spectacle if they made it mandatory that the cars had to have a certain amount of suspension travel these days.”

I ask about the GT steering, and Amon’s face lights up even more.

“This car really makes you appreciate good steering feeling. There’s not much around these days with this much feel.”

Was there anything the chassis set-up consultant to Toyota would change?

“Absolutely nothing. It felt very driveable, with enough power to steer it through the corners with the throttle. You could have a hell of a lot of fun in this car.”

He’s also impressed by the build quality and user-friendliness.

“If you were using this on a regular basis, I imagine it wouldn’t be that expensive to run, especially when compared with sundry Ferraris and their like.”

Peter Walton, the GT’s owner, is also fizzing about his new purchase, especially its visual link to such a great day in New Zealand’s motorsport history, and the keenness of one of his heroes to accept the invitation to drive it. He produces a stack of GT40 historical books for Amon to autograph. It’s a task Chris probably hasn’t been practising much since the Goodwood Festival of Speed in 1997, where he drove an historic Ferrari F1 race car and the Ferrari 512 sports car of Pink Floyd drummer, Nick Mason. These days, the man Enzo Ferrari rated as one of his finest drivers lives a quieter, semi-retired life on the shores of Lake Taupo.

Almost fifty five years ago, Amon opened the throttle of a ‘long-nose’ GT40 wide open while entering the Mulsanne straight on the first lap of the 1965 Le Mans 24-hour race, and witnessed the competing Ferraris shrinking into “tiny little specks in my rear vision mirror”.

“The 1965 version of the GT40 was the fastest, with about 10-15mph more speed than the 1966 short-nose version [with which Ford first won the race]. However, Ford took the decision to reduce the body’s lift at top speed with aerodynamic changes, and this resulted in more drag, and a slower car.”

Amon, after being refused a start by the organisers of the 1963 Le Mans 24-hour “for being too young”, was involved with the GT40 programme from its birth in 1964. Inspired by Henry Ford II’s desire to “kick Ferrari’s butt” after the Italian refuted Ford’s takeover offer, the GT40 would dominate sports-car racing throughout the last half of the 1960s, its test development programme often led by the feedback provided by Amon. The car evolved from a 4.2 litre V8 to a 7.0 donk in the lead-up to the 1965 Le Mans race.

“1965 was an absolute shambles… On the eve of the race, they chucked all the 289 [cubic inch] engines out and stuck in 325s, which I don’t think had ever done 24 hours of testing, let alone a race. They all did head gaskets.”

Ford learned plenty from the ’64 and ’65 campaigns where no GT40 completed the Le Mans event, and this experience set it up for total domination of the 1966 race. Amon and fellow Kiwi driving partner, Bruce McLaren, were contracted to Firestone at the time, and found themselves hampered by a lack of tyre durability in the early stages of the race. Some swift negotiating by McLaren saw them swap to Goodyear tyres, and they drove flat knacker to catch the leaders. With the Ferraris dropping like flies as the final quarter of the race approached, it was clear a Ford GT40 would win; the only problem was which one? Controversy still surrounds the victory of the Kiwi-driven GT40, as some in the camp thought the Ken Miles/Denny Hulme car that came second should have triumphed. Did McLaren sell the idea of a three-car dead-heat finish to the team (a là the Bentley boys of the 1930s), and then renege on the deal? Amon smiles wryly as he responds:

“There was no way Bruce was going to finish second.”

Many still debate the Machiavellian nature of Amon’s biggest race win, especially as Miles was killed a couple of weeks later while testing the ‘J-car’ prototype. It was a car in which Amon, as the other driver in Ford’s sports-car test programme, also had experience.

“It was the first car that had the suspension uprights glued to the chassis instead of bolted or riveted as well. I used to wonder whether the thing was going to fly apart at speed as the adhesive technology they used was still in its infancy.”

Four decades on, it’s easy to wonder about all the narrow escapes with death that Amon must have survived to achieve this rendezvous with the Ford GT. He raced in an era still coming to grips with advances like adhesives and aerodynamics, a time when death was the motorsport professional’s constant companion. Peter Walton comes up, and invites me to drive his car, then begins to thank Chris for coming. Amon cuts him short with a comment I’ll treasure for the rest of my life:

“Thanks Peter, but I’m going to stick around for a bit longer to hear what Paul thinks of the car.”

So I move away from one of my driving gods into the son-of-god car inspired by his greatest victory. Getting seated in the GT is no more demanding than a Mondeo, provided, I guess, nothing is obstructing the near-90 degree swing of the generous doors. They need to move out that far because half the roof comes with them, the cutaways enabling easy access and egress for a car just 1.1 metres high.

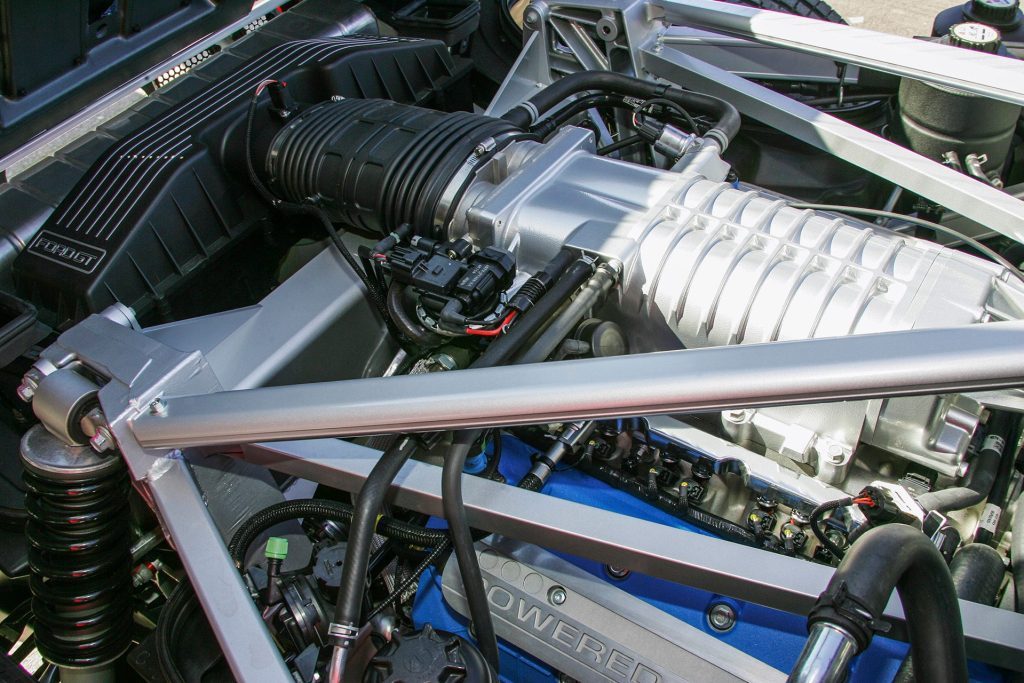

With a push of the silly start-button, the 5.4 litre supercharged V8 nestled behind me bursts into song. The V8’s bore and stroke dimensions are the same as the engine found in sundry BA Falcon V8s, but the whirr of the Eaton supercharger brings a new edge to the familiar tune it sings. As I snick into first and let out the long-travel clutch pedal, I’m aware of how much more willing to rev this motor is than an XR8’s. Special twin injectors, shot-peened conrods, forged-alloy pistons, and a forged-steel crank have added a more race-ready persona to a donk first intended for duty in the F150 Lightning pickup truck. Meanwhile, the dry-sump lubrication enables the engine mass to be carried lower within the extruded alloy spaceframe. The gearbox lever is suitably stubby, and gives access to a race-strength six-speed with an absurdly strong attraction to the middle plane of the double-H gate.

I enter the race circuit with Peter riding shotgun, but he might as well be in another car. Between us is the wide alloy centre tunnel that is the space-frame’s ‘spine’. We’re both comfy and relaxed in the supportive Sparco seats, and after I’ve done a tentative first lap in Peter’s spanking-new supercar, he gives me his blessing to go harder.

The GT responds like a Doberman on speed that has just been let off its leash. Second and third gears are all that’s needed in Taupo’s tight circuit, but they access an engine that’s as happy lugging second gear off the constricted hairpin as it is at maximum revs in third at the end of the back straight. There’s power and torque delivered right through the rev range, a total contrast to the Eyetie screamers that are the GT’s price-point competition. There’s also no traction or stability control to help tame the generous output of the engine into traction. The GT driver must instead put total faith in the fat Goodyear Eagle F1 supercar tyres, the torque-sensing limited-slip diff, and his/her own car control. This is, finally, a non-Italian supercar tailored totally for the purist.

In keeping with that focus, the messages from the tyres arrive at the GT’s driving interface loud and clear. If the small-diameter steering wheel wasn’t circular, you could easily imagine that you were holding the front axles in your hands. Through the thin but adequate padding of the Sparcos come dispatches from the coffee-table-wide rear tyres with all the clarity and instant gratification of email. In my handful of laps, the Goodyears lose their purchase on the track just once, while exiting the left-hander onto the back straight. Such is the diff’s response there is no need to apply opposite lock to quell the oversteer, thanks to a quick seesaw of torque distribution between the two rear tyres. The over-achieving Ford merely hooks up and drives relentlessly on.

To those used to the full-throttle drive of a Ferrari F430 or Lamborghini Gallardo, the GT won’t cause any shellshock with its acceleration. Admittedly, Peter’s car was brand new, with an engine tighter than any finance minister the Act Party could appoint, yet there was always a suspicion that the power and torque claims were figures chosen because they’re easy to remember. The 373kW and 678Nm peaks translate conveniently to 500bhp and 500ft-lbs, respectively, in North American terms. With the identical power-to-weight ratio as the Gallardo (241kW/tonne), I’d also expect the GT to achieve the same 5.23-second 0-100km/h sprint we measured in the Latin supercar, rather than the 3.8s performance that Ford claims.

If the engine performance was only really impressive in the wide nature of the power delivery, it was the chassis that staked the GT’s claim to greatness. Without the luxury of a road drive, I’m happy to declare this the finest-handling car I’ve driven. Not just the finest-handling mid-engine car, but the finest car, period. It’s the extraordinary chassis balance that makes it win such a grandiose place within the range of my driving experience. The torque that the engine delivers to the rear wheels is the key to the GT’s cornering attitude. You quickly find the sweet point in the throttle pedal’s travel that optimises the four-wheel drift of the car through any particular corner, be it one of the faster jinks on Taupo’s curvaceous front straight, or the 250-degree hairpin. It’s easy to be clinical, efficient, and devastatingly quick with the GT, and I suspect it would have been just as easy to play the lairy power-sliding hoon – not an aspect to be explored with my passenger aboard.

All of which adds nothing of real substance to Chris’s original impressions of the most outrageous, most expensive Ford ever. I emerge from the GT, bump my head on the bit of the roof still attached to the door, and do a passable impression of a parrot to our patiently waiting guest test driver. Except this ‘Polly’ wants something rather more expensive than a cracker. I wonder if Santa’s sleigh has room for a right-hook GT…

| Model | Ford GT |

| Price | $216,000 (approx) |

| Engine | 5409cc, V8, SC, EFI |

| Power | 373kW/678Nm |

| Drivetrain | 6-speed manual, RWD |

| 0-100km/h | 3.8sec (claimed) |

| Weight | 1540kg (claimed) |

This article was first published in the October 2005 issue of NZ Autocar Magazine.