It’s taken 40 years to get there but Mazda’s original RX-7 is deservedly coming of age. For a spell, the RX-7 was the poster child of the ‘boy racer’ set. As their residual values plummeted and bottomed out towards the end of the 1990s, the first generation RX-7 epitomised Kiwi ‘street’ rotary culture – love it or loathe it. Their affordability during this period ensured they were a popular choice for the ‘enthusiast’, resulting in some fairly dubious examples roaming the night, keeping the nation awake to the tune of ported rotary engines. Many once fine examples suffered shoddy mods, theft and often succumbed to physics at the hands of talentless pilots.

For every beater that spent it’s life baking a pair of Bridgestone Eagers at the local skid spot every Friday night, there were as many spit-shined show ponies, pushing boundaries of detail and innovation. The 240Z may well be revered as the first ‘everyman’ sports car out of Japan but the RX-7 stakes a solid claim to be one of the most ubiquitous.

The RX-7 has contributed much more to the Kiwi motorsport scene on both tarmac and gravel. This is the Japanese sports car that damn near every car enthusiast here has a story about, for better or worse.

Some years down the track, nostalgia kicks into gear, and those who owned, or wanted to own one of the early generation cars find themselves seeking out the best example they can. The zenith of these RX-7s has to be the Savanna Turbo variant which was reserved exclusively for the Japanese domestic market (JDM) of the era.

But first, a little of the RX-7’s back story. On a global scale, prior to the RX-7 hitting showrooms in 1978, Mazda’s rotary efforts amounted to what were essentially a range of saloons with a dab of sporting intent. Sure, the L10 Cosmo of the late 60s had an air of sportiness about it, but only the Japanese were able to revel in its 10A twin-rotor glory.

Outside of the domestic market, Mazda chose to woo the west with the ‘smooth rotary power’ in the likes of the R100, RX-2, RX-3 and RX-4. Along with outliers, like the USA-only Rotary Engined Pick-Up (REPU), the rotary offerings developed a reputation as potent sports saloons, albeit with dubious reliability and economy thanks to their unique rotary power plants.

These sedans and coupes would develop Mazda’s sporting provenance in tin-top series across the planet, from full-throttle runs down the Mulsanne straight to spraying gravel North of Maungaturoto. With a reputation cemented as a low-cost, high performance option, Mazda needed a follow-up strategy that resulted in the RX-7, or Savanna, to its home buyers.

With a design team captained by Matsaburo Maeda, Mazda unleashed the RX-7 on the world in 1978. The silhouette was pure sports car. A low, set-back glasshouse, and long protruding bonnet with pop-up headlamps that, when retracted, endowed the compact 2+2 sports car with a slippery 0.36 drag coefficient.

Underneath, things were fairly simple. A proven Mac strut front end with discs and a drum-braked, four-link, coil-sprung live axle at the rear meant Mazda wasn’t out to reinvent things on the chassis front. But under that low-lying bonnet was the trump card; a 1146cc 12A rotary. The packaging of the rotary engine meant Mazda had leeway to mount the mass low, and rearward of the front axle. This gave the RX-7 near to even weight distribution, and total mass came in at around 1000kg, light enough for the 12A’s 100hp to propel the car at more than acceptable pace.

Despite the relatively low-tech underpinnings, the RX-7 found favour with testers of the day, who praised its precise road manners and communicative handling.The rev-happy 12A was noted for its smooth power delivery, and the positive shift of the five-speed gearbox.

The first generation RX-7 would enjoy two facelifts through its seven-year production run, first in 1981, then again in 1983, which is when the ultimate development in the SA-22C story would occur.

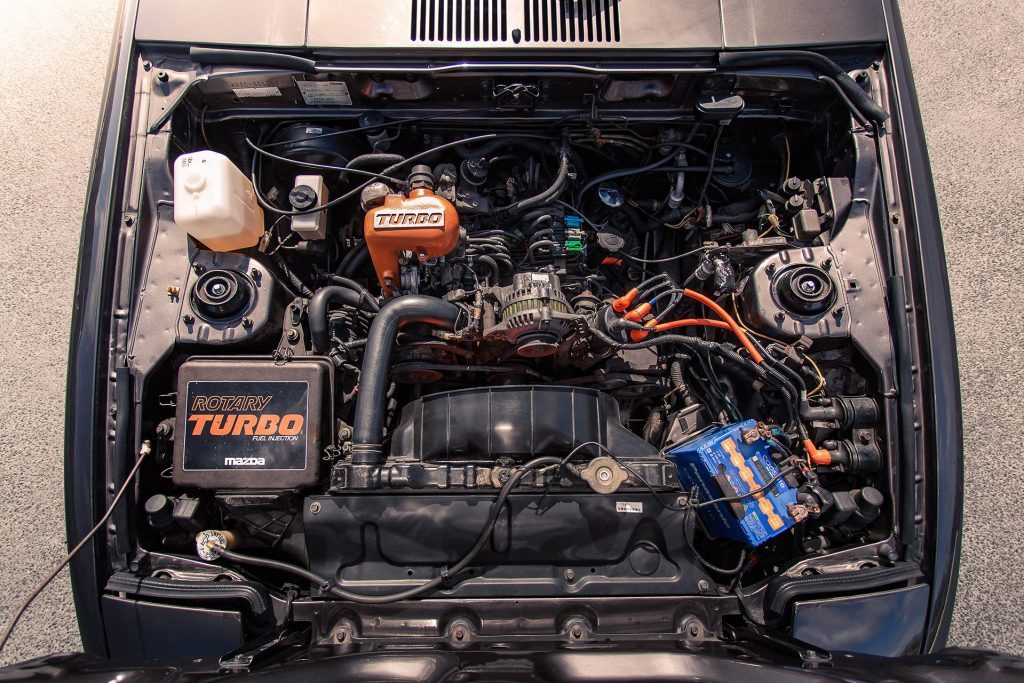

Toward the end of 1982, Mazda decided that the 12A needed a boost. Not only did it receive a turbocharger but also fuel injection. The 12A turbo would first find its way into the HB Mazda Cosmo.

Versus its six-port, naturally aspirated Cosmo stablemate, the 12A turbo featured a four-port intake design, and a modest drop in compression to 8.5:1 to cope with an equally modest (by modern standards) 6.2psi of boost. The fuel injection was an analogue unit, produced by Denso, driving injectors mounted in a ‘semi-direct’ arrangement, very close to the port opening in each rotor chamber. All said and done, it was good for 160hp, which was enough to propel the Cosmo to the title of ‘Japan’s fastest sedan,’ for a short period of time.

While a turbocharged rotary sedan with sporting intent was all well and good, the RX-7’s halo was about to glow brighter, for in September 1983 Mazda introduced the RX-7 turbo in Japan. The 12A turbo benefitted from some upgrades for duty in the 7, namely an uprated Hitachi turbocharger, featuring revised turbine geometry to capitalise on the rotary’s high rate of airflow. The result offered a five horsepower bump in peak power and a slight increase in torque, with Mazda’s own Tokyo Auto Show press release noting no “noticeable turbo lag, which is often characteristic of the turbocharged piston engine.”

Accompanying the 12A turbo was a raft of small chassis improvements to the third and final RX-7 facelift. Revised rear suspension control arm mounts, suspension bushings and a smaller rear antiroll bar further refined the RX-7’s handling.

But what’s it really like to drive? Despite what a period press release might say, early turbo cars are laggy, right? And rotaries are noisy, peaky things aren’t they? At least that’s what the multitude of modified tyre-frying, ported examples out in the wild would suggest.

Taupo’s Aidan Barrett, a man with a bit of a weakness for rotary engined Mazdas, was kind enough to chuck the keys our way for an afternoon, to experience his near-factory spec 1984 example.

Taking in the styling, the RX-7 isn’t an intimidating car by any stretch. Even in this final facelift guise, it’s still an attractive, unfussy design. Mazda saw fit not to adorn the Turbo with flares, scoops and aero devices, although it does wear a subtle spoiler on its rear deck. Instead, the later model incorporates wrap-around plastic bumpers, painted in body colour, that smooth out the 70s design.

Inside, the RX-7 Turbo reflects the era it was designed in. It perhaps hasn’t aged as well as its pretty exterior aesthetic. There were three trim levels available for the Japanese market RX-7, the base GT, the up-specced GT-X and the top-of-the-line SE Limited. Aidan’s car is a GT-X, equipped with a set of moderately sporty, velour-trimmed buckets, facing a dash that had changed little since the RX-7’s debut.

There’s a certain charm to 80’s colourways, something that only now seems to be gaining acceptance in the classic sphere. Multi-toned greys contrast with faux brushed alloy surfaces, and in an era of plastics that never seemed to age robustly this car is pretty damn tidy, though tactility isn’t a high point. Instrumentation is driver focused, with a concise binnacle housing a no-nonsense cluster. The tacho takes centre stage, redlining at 7000rpm, while the obvious change to the Turbo is the inclusion of a boost gauge, letting the driver know when that Hitachi turbine is properly on the boil.

Settling into the somewhat plush – it’s probably a stretch to call them supportive – buckets, the RX-7 feels an intuitive place to be. The seats are set low relative to the dash, enhancing the long nose, short deck proportions from a driver’s perspective. The bonnet stretches and dives away for what seems like miles. Conversely, it feels like you’re effectively sitting over the rear axle, yet the drive controls are all close by.

The rotary cranks for longer than initially seems comfortable, before settling into a rhythmic hum on idle, enhanced slightly by this particular car’s aftermarket exhaust. There’s no real theatre, none of the expected harshness thanks to preconceived ideas tainted by years of exposure to modified examples. The 12A seems civilised and refined, as is the clutch as it eases out.

There’s no real superlative needed to describe the way the RX-7 drives. Simply put, it’s easy. The car is light on its feet, the steering precise and not requiring any sort of Herculean effort to point it in your desired direction.

As the pace quickens, and the slick five-speed is run through its gears, the balance of the RX-7 is appreciable. The front end responds obediently to steering inputs, and with the seating position so close to the axle, the rear end grip feels accessible and communicated. This era of RX-7 captures those core elements of driving, despite Mazda’s efforts to modernise it.

But let’s talk about that 12A turbo.If you’ve never had the opportunity to drive a well-sorted, OEM-spec Mazda rotary, it’s an experience that surely needs to be on the bucket list for any petrolhead. The little 1146cc mill spins effortlessly towards the danger zone on the tacho, almost too easily. There’s no unwanted resonances or harmonics and, unlike it’s turbocharged stablemates of the era, lag is minimal, or at least disguised well by the 12A’s smoothness.

It’s no stump-puller but power delivery comes on proper around 3500rpm, building through the rev range. It’s a momentum car for sure; you want to be pushing this through your favourite twisty road right in the meat of its rev range, somewhere north of 4000rpm, to capitalise on peak torque. Rowing through the gears, you revel in feeling everything that the front tyres have to offer and are confident the rear is talking enough to provide ample warning when it tries to come around and meet the nose.

The RX-7 is the epitome of a balanced chassis and, unfettered by modern aids, it’s a must-do driving experience. This helps banish the old preconceptions of the boy racer machines. The RX-7 is no longer the cheap and cheerful entry to the rotary world; it’s a genuine classic.