Why hydrogen is not the miracle fuel many are hoping for

Words NZ Autocar | Images BMW, Toyota

People keep asking whether hydrogen is the fuel of the future, and if so when it will supersede electricity and EVs. Well the answers are – it has a place, at present extremely limited, and it will not replace BEVs. Long story short – don’t get your hopes up.

People also ask why don’t firms who make internal combustion engines simply replace petrol and diesel with hydrogen. BMW for one says “it gave up on hot hydrogen technology years ago”. Research proved that the combination of hydrogen and ICE was unsuitable for the needs of passenger vehicles.

A BMW expert in hydrogen, Juergen Guldner, told Go Auto that hydrogen technology may be suitable for some applications. But practically speaking it did not make sense in conventional passenger vehicles.

He said “We actually started with hydrogen combustion engines almost 20 years ago but we stopped that because of the lack of efficiency”.

“With a hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicle (FCEV) we get around 500km from a tank. With a hydrogen combustion engine in the same car with the same tank, we wouldn’t even get 300km. That is the difference between a product we can sell and one we cannot sell.

“At the 500km mark, and with a refuelling time of three to four minutes, I think people will consider making the move to hydrogen so it is relevant.”

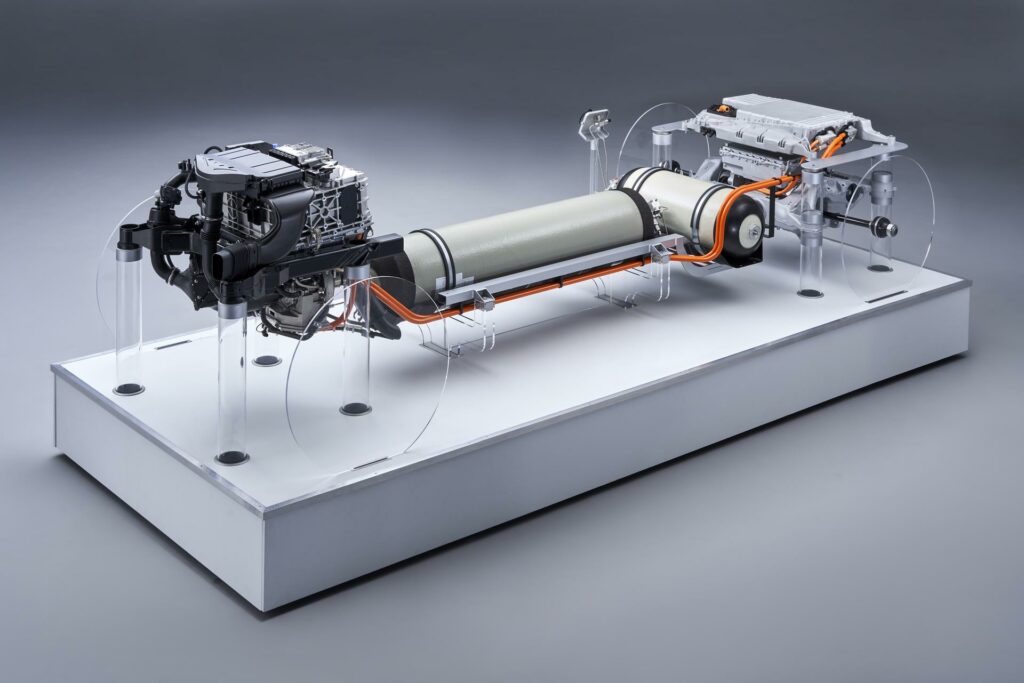

On the other hand, FCEV technology does not come cheap. The fuel cells themselves are expensive. Think EVs are high priced? FCEVs are in another league of expensive. An FCEV, by the by, is essentially an electric car – the same motor drives it. Instead of electricity in a battery, gaseous hydrogen is stored in tanks and converted into electrical energy for the drive unit by means of the fuel cell.

Another issue with FCEVs is the additional weight of the hydrogen fuel tanks and the space they occupy (to the detriment of luggage capacity). And then there’s the almost complete absence of refueling infrastructure. Moreover, production of hydrogen is carbon intensive. So FCEV technology is up against it. Ask BMW when they will have an FCEV to sell and they suggest the latter part of this decade.

Efficiency concerns have also been noted by Toyota. Its hydrogen-powered HiAce runs a lightly modified twin-turbocharged 3.5-litre V6 combustion engine. With hydrogen it manages output of 120kW and 354Nm. With petrol it produces 305kW and 650Nm. Furthermore, the hydrogen model’s range of 200km falls miles short of the petrol-powered HiAce Commuter’s 600km per tank.

But BMW’s Guldner said that hot hydrogen technology may prove to be a cost-effective in certain situations, converting commercial fleets to cleaner energy.

“The story is different for trucks and for racing. You need power (in these applications), and a combustion engine can deliver more constant power than a fuel cell in the available engine bay space.

“There are also hydrogen combustion engine trucks and here the efficiency difference is not as important.

“A truck runs constantly, and the efficiency of a combustion engine is better when you run at a constant speed.” Plus, trucks can carry more hydrogen tanks for greater distances between refills.

Both BMW and Toyota suggest the future of transportation is one that will become multifaceted depending on the application.

Battery electric suits smaller commuter cars, larger passenger vehicles will use hydrogen fuel cell technology, and commercial vehicles will employ a mix of energy sources, potentially for decades to come.

In that sense, hydrogen is only part of the solution moving forward – it is certainly not the silver bullet many are hoping for.