2003 FPV GT review

Words Paul Owen | Photos Adrian Payne

Battle of the bulge – no, it’s not the historic last-gasp offensive of the german army in WWIIi. Nor the perennial fight against middle-age spread. It’s the fight of the new GT from Ford Performance Vehicles for V8 sports-sedan supremacy after entering the fray with a truck engine nestled beneath its bulging bonnet.

The prominent protuberance poking through the bonnet dominates the car from inside and out. The size of a bull elephant’s scrotum, the engine cover bulge of the new FPV GT is the automotive sheet-metal equivalent of Mount Everest. While not really quite as imposing as Sir Ed’s hill, it does tend to raise some questions in the mind of a long-distance road tester as he peers over it:

Mental memo No.1: Is this a Pro Stock drag-racer I’m driving today? Because if it is, it’s a little slow off the mark.

Mental memo No.2: It goes around corners like no drag car, and has plenty of mid-range power – so that bulge must cover some form of forced induction system, right?

Wrong. The bonnet bulge the GT shares with its lesser Falcon XR8 brethren is a design feature deemed necessary to clear one Incredible Hulk of a truck engine. The long-stroke, cast-iron V8 cylinder block was originally designed for the gargantuan Ford Expedition, an XXL-sized SUV that makes an Explorer appear as petite as Kylie. Engine bay space isn’t an issue for an Expedition – it’s quite possibly big enough to swallow two of these 5.4 litre mills. However, a BA Falcon is a different kind of animal. Although a large car by Australasian standards, it’s a little short of accommodation when squeezing in any V8, let alone one primarily designed as a truck engine with piston stroke dimensions roughly 18 per cent larger than the bore diameters (bore: 90.2 mm, stroke: 105.8 mm). There’s just three millimetres of clearance between either side of the undersquare motor and the suspension towers under the GT’s bonnet, and the car is in clear breach of a Ford standard requiring 20 mm of clearance all around the engine.

The red tape also got gas-axed for the GT’s newly developed dual-overhead-cam alloy cylinder heads, which make their world debut in the latest XR8/FPV GT sports-sedans. Dubbed U231, these four-valve-per-cylinder heads were fast-tracked from engine development dyno cells in Detroit to propel Ford Australia’s latest V8 offensives against Holden and HSV down under. Cams and compression are what separate the XR8 version of the engine from the GT. They’re responsible for a difference of 30 kW and 20 Nm between the two Falcon-based sports-sedans. The XR8 develops 260 kW and 500 Nm: the GT 290 kW and 520 Nm. They’re impressive figures for either car, the XR possessing more power and torque than the most popular 250 kW HSVs (let alone the real target: the 235 kW Commodore SS), and while the range-leading 300 kW HSV models have 10 more kW than a GT, they have 10 Nm fewer at their disposal, and cost $30,000 more in their state of origin. Never have Capt’n Crennan and the HSV crew been under such a sustained V8 attack from the bearers of the blue flag.

The GT develops the extra through the use of heavier (by 47 g) cast pistons, which raise the compression ratio from the XR8’s 9.5:1 to 10.5:1, plus lumpier Mustang Cobra R camshafts that increase inlet valve lift from 10 mm to 13, and exhaust valve lift from 10 to 12mm. Both the XR and GT share the same straight-shooting induction system – 75 mm throttle bodies with electronic operation – and consequently, the same bulging bonnet. Ford points out that this allows optimal mounting within the tight engine-bay space, improved cooling, and adequate sump clearance on dusty dirt roads down under. They also hail the new Boss V8s as the first 32-valve quad-cam V8 engines ever offered in Australian sports-sedans.

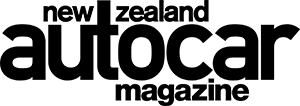

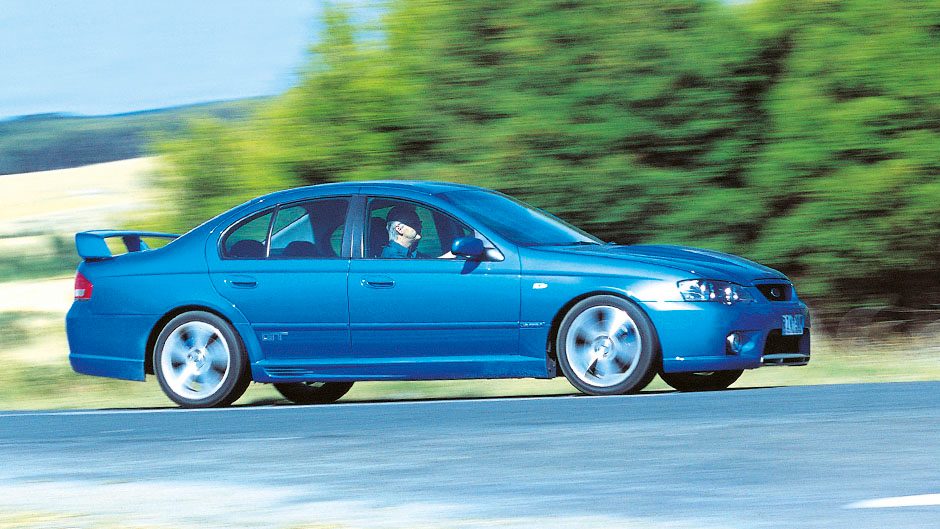

However, those raised on a diet of high-performance V8 engines from Europe, as well as those championing Holden’s Corvette-sourced all-alloy unit, will query whether the truck-blocked motor of the GT/XR8 really suits sports-sedan applications. The power peak arrives at sub-6000 rpm engine speeds, and from the first glance at the tachometer the lack of a red no-go zone is immediately apparent. Why is FPV being so coy about maximum engine speed? Let’s head out on Australia’s finest road – the aptly named Great Ocean Road between Melbourne and Adelaide – to find out…

Here, on this sinuous, cliff-hugging highway with little opportunity for overtaking, Volvo-man is obviously having a Rickard Rydell fantasy. Ever since the bright-blue Ford V8 appeared in his mirrors, he’s been pitching his S40 into the turns so hard we can hear the tyres protest from the FPV GT’s cabin. The Swedish car would push wide with understeer, running across the centre line on left-handers on occasion, and threatening to morph with unforgiving roadside rock formations when turning right. Volvo-man, like so many the safety-first Swedish cars attract, must think his comprehensive airbag armoury has made him Mr Invincible. Yet no car resulting from 50 years of dedicated safety research stands a chance of protecting its occupants fully when colliding with 500,000-year-old rocks that have endured the ravages of time since before dinosaurs became fossil fuel. Now to file this S40 into the GT’s mirrors at the earliest opportunity…

A small straight beckons. A quick double-clutched downshift into the second ratio of the Tremec TR3650 five-speed gearbox locks the engine on to the 4250 rpm torque peak target, and we move into the lane of the oncoming traffic, and pull the trigger of the drive-by-wire throttle. The V8 slingshots the GT forward with a lusty bellow and a wicked turn of speed – then just as abruptly, dies. We’ve hit the 6000-rpm rev-limiter. A quick upshift into third gets us past the Volvo with room to spare, but it would be nice if the GT’s staunch refusal to rev past six arrived with a little more warning. A programmable shift-light perhaps, given that they’re all the current rage in sports machines.

That way, Ford would still be able to disguise the rev limitations of the Boss V8’s long-stroke architecture, rather than advertising them with a red zone printed on the tachometer fascia. One can understand why the 6000-rpm limit is strictly adhered to, given that higher engine speeds would see those heavy pistons travelling at more than 5000 feet per second in the cylinder bores. Look no further than the lumpy idle and rocking motions of the GT when waiting at the lights for the best illustration of the mechanical Wagnerian opera taking place under the bonnet. You feel every stop of the pistons at top-dead-centre before their plummet back towards the crankcase, and can easily imagine the expensive explosions that might occur at 7000 rpm. Ford says it opted for the long-stroke Triton-series block because its research says the Aussie V8 buyer is looking for strong bottom-end and mid-range performance, and alternatives such as supercharging the rev-friendly 4.6 litre V8 of the current Mustang wouldn’t meet this criteria.

Yet the Boss 290 of the GT is compromised by over-zealous gearing when it comes to top-gear overtaking. Although the 0.675:1 fifth ratio is shorter than the 0.625:1 chosen for the last 5.6 litre T-series Falcons, a downshift – or two – is still mandatory to keep overtaking safely swift. There is also a noticeable lift in engine performance above 4000 rpm, courtesy of the Cobra R cams, and getting the best out of the GT requires chasing the upper 2000-rpm fast-and-furious zone with the five-ratio Tremec (a four-speed Aussie-made BTR automatic will come on line in a few months). This is no chore, thanks to careful attention to clutch action and pedal layout, but it will be interesting whether the softer cams of the Boss 260 fitted to the XR8 result in a more even power delivery, not to mention a more even idle.

The XR8 will have trouble emulating the HSV-humbling performance of the GT, however. Our new VBOX data acquisition system identified a 0-100 time of 5.8 seconds, and the GT would have gone even quicker if the 6000-rpm rev-limiter hadn’t chimed in at 99 km/h in second gear. For the record, that’s still 0.1 of a second faster than the last 300 kW HSV GTS manual tested, despite the up-shift into third needed to reach 100 in the Ford. However, the 80-120 km/h performance was a tick slower, the FPV recording a 3.6-second kick versus the 3.2-s overtaking sprint of the GTS.

The latter illustrates that this is still quite a peaky engine when it comes to power delivery. Best overtaking times of both FPV and HSV were recorded using a combo of the second and third ratios, yet the same 0.4 of a second difference continued using just third: 4.5 seconds in the blue-badged car, 4.1 in the HSV. FPV turned the tables when it came to braking performance though. We hailed the GTS as the quickest-stopping Aussie V8 ever when we tested it, but the FPV emphatically stole that crown by halting from 100 km/h in 34.66 metres of road where the HSV took 36.20 metres. The optional Brembo brakes (standard on the GT-P model) made all the difference in stopping distance. These feature discs 30 mm larger, and four-piston calipers front and rear. Although the standard FPV brake package is beefier than that of a BA Falcon, the extra safety and resilience of the Brembo option made its presence felt on the winding roads of the drive programme. We can’t recommend them highly enough.

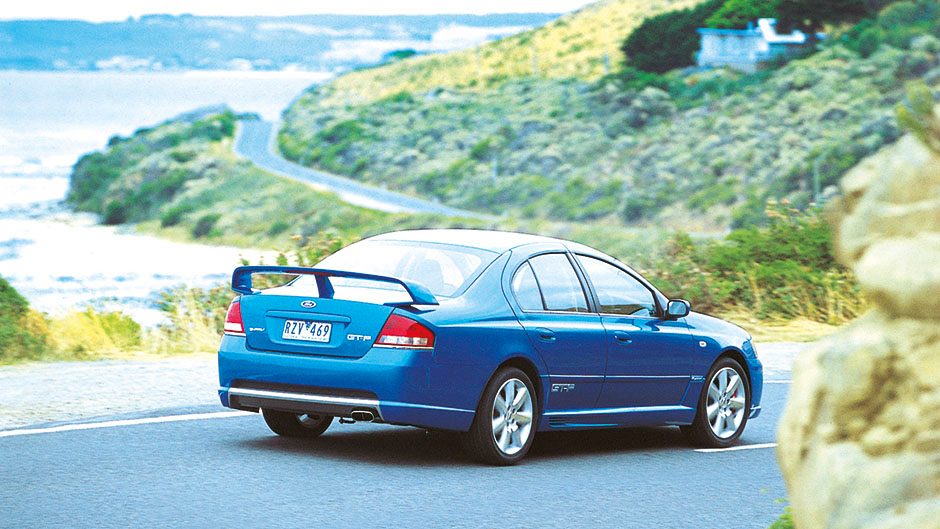

Also worthy of our vote of confidence is the handling of the FPV sedans. The agile steering of the cars quickly dispelled any fears that the huge, cast-iron block of the Boss V8 might have adverse affects on centre of gravity and balance. This is no hippopotamus wearing a pink ballet tutu, and it always feels a smaller car to chuck around. The weight distribution might be 56 per cent front-biased thanks to that mother lode of cast iron resting on the front axles, yet the GT handles like it’s achieved the lofty ideal of 50:50 distribution. With the standard-fit traction control turned off, the GT delays understeer until cornering speeds well above those of the average family sedan (well above a certain S40), and then gives the opportunity to set up a gentle four-wheel drift with the throttle. If the engine speed is above 4000, there’s also a game of ‘chasy’ with the tail of the car on offer at the throttle-on moment. Coupled to steering that lets the driver know exactly and clearly what’s happening at the front tyre/road interface, this mix of road-holding and throttle-adjustable handling puts the GT in the master class of driving dynamics.

When you’re not in the mood for such fun and games, or the traffic on a tight and twisty road has brought an early halt to them, the FPV’s ability to pamper comes to the fore. According to head FPV product planner, Gordon Barfield, it was the BA Falcon’s increase in body rigidity that allowed the engineers to use suspension settings that target ride comfort as much as they encourage sporty driving. Although the spring rates are 50 per cent heftier than in a cooking Falcon sedan, damping isn’t delivered with the same harshness you’ll experience in the average HSV. This results in more compliance on bumpy bends, and less tendency for the undulations to influence the steering of the car.

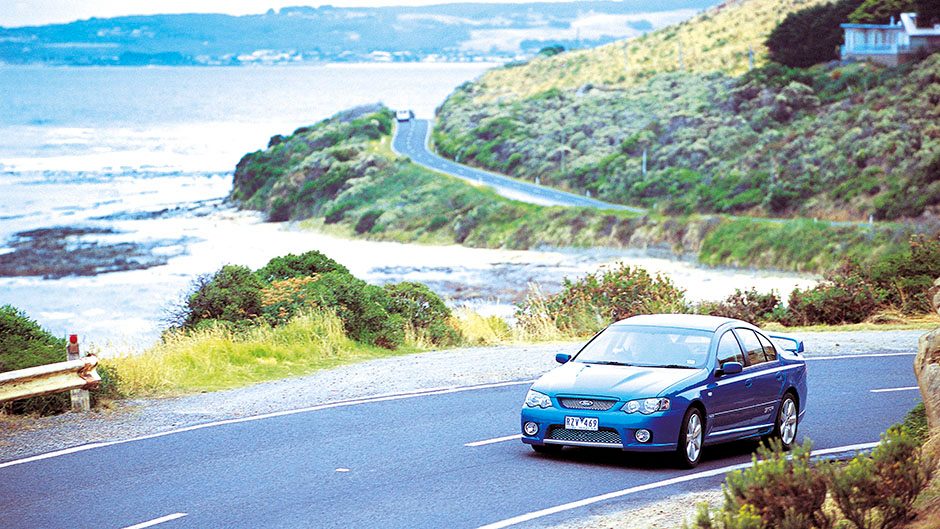

There’s a refreshing lack of tram-lining at the wheel of the FPV, especially when compared to the direct competition. So consider the FPV family, Pursuit ute aside, to be the equal of European sports-sedans when it comes to targeting a ride/handling compromise worthy of the ‘Grand Touring’ tag. It’s a comparison that pales a little when it moves to the interior, which has little to distinguish it from the BA brigade, despite the suede-covered sports seats, naff start/stop button and drilled alloy pedals. The two sedans, GT and GT-P, are distinguished by their origins: Falcon for the GT, and Fairmont for the GT-P. The latter shares Fairmont’s dual climate control, larger LCD information display, trip computer and six-disc in-dash CD player. The one without the P on the end comes minus the quick-stopping Brembos (the only engineering compromise), but enjoys a 100-watt single-CD audio, manual air con, cruise control, split-folding rear bench, Momo steering wheel and gear-lever knob, 18” alloys, ABS with EBD, and adjustable lumbar support for both front seats. Aussie pricing kicks off at $A59,850 for the GT – which strangely asks another $1150 for the automatic version – while the GT-P costs $69,850 for either transmission choice.

New Zealand’s price regime has yet to be finalised for the June arrival of the FPV GT family, but given an opportunity to revise the range, we’d make a few changes. Knowing the legend of the Falcon GT nameplate, we’d have a one model range so as not to dilute the heritage of the car, with the GT-P’s Brembos and higher-bolstered seats included as standard equipment. Then an options list á là Porsche would allow all manner of interior customising, such as carbon-fibre trim packages and 13-speaker audio upgrades. A FPV GT specced in this manner would still make a much more affordable alternative to a 300 kW HSV. However, there is one item we’d consider ditching: an 8000-rpm tachometer has no place on a car that gasps as soon as it reaches 6000.

| Model | 2003 FPV GT | Price | $75.000 |

| Engine | 5408cc, V8, EFI, 290kW/520Nm | Drivetrain | 5-speed manual, rear-wheel drive |

| Fuel Use | XL/100km | C02 Output | Xg/km |

| 0-100km/h | 5.8sec | Weight | XXXXkg |