BMW M3 Sport Evolution vs Mercedes-Benz 190e Evolution II

Words/Photos: Richard Opie

What’s motorsport without its fierce rivalries? In Germany the brand tribalism centred around Mercedes-Benz and BMW. This pair of 1990s superstars epitomises the DTM landscape of the era.

As any Kiwi motorsport fanatic knows, tribalism plays its part when rooting for your preferred podium-fillers. Locally, the touring car rivalry is typified by the true-blue Ford nuts and the red-blooded Holden lunatics. Or at least it has been.

With the demise of Holden, it’s about to shift from those fair dinkum Aussie marques to being an exclusively American affair with Ford’s Mustang squaring up against GM’s Chevrolet Camaro – and so the red and blue war will continue.

To the casual observer, it could be viewed as something exclusive to the Australasian motorsport sphere. After all, those weirdo Europeans race just about anything, right? So loyalties surely are splashed all over the joint akin to a Jackson Pollock piece.

As touring car racing headed into the twilight years of the Group A era, many German benzin kopfs would have argued their local Deutsche Tourenwagen Meisterschaft (that’s German Touring Car Championship, or DTM for short) represented one hell of a marque vs marque rivalry, thanks to BMW and Mercedes-Benz.

True, Audi made waves with a pair of victories in 1990 and 1991 thanks to its monster V8 Quattro. However, the brand from Ingolstadt still lacked the longer-lived credentials of its Stuttgart and Munich counterparts.

The “elbows out” nature of DTM competition of the 90s helped elevate this BMW vs Mercedes-Benz rivalry to the world, and cemented the DTM battlegrounds as some of the greatest touring car racing of all time.

The Three-Pointed Star Strikes

Given BMW’s previous endeavours in touring car racing prior, you would have expected them to roll out their ultimate Group A contender first but Mercedes beat them to the punch with the W201 chassis 190E, which would eventually morph into the flamboyant Evolution II.

Initially, the 190E 2.3-16 came about through a desire to go rallying. Mercedes figured their brand spankers W210 190E sedan had the stones to take it to the established two-wheel drive contenders, so enlisted Cosworth to develop a hot version of their cast iron M102 four pot.

They would develop an alloy twin-cam head, fueled by Bosch KE Jetronic injection, with 10.5:1 compression to deliver a handy 185hp. Getrag provided a dog-leg five-speed manual, with bigger brakes lurking beneath 15×7-inch Fuchs Gullideckel wheels.

Mercedes also lowered and stiffened the MacPherson strut front and multilink rear independent suspension (with hydraulic self-levelling rear shocks) and fitted an appropriate aero kit to distinguish the hot 190E from its pedestrian counterparts, as well as provide the edge in competition.

By the time the 190E 2.3-16 debuted at the Frankfurt Motor Show in 1983, and production subsequently commenced 12-months later, the rallying mandate had all but disappeared. That ‘other’ German marque, Audi, was wiping the floor with their all-wheel drive turbocharged Quattro. As such, Mercedes chose instead to forgo the dirt, and head to the tarmac.

Group A was the hot ticket in touring car racing. Mercedes needed to build 5000 examples to homologate the car, and then they could hit the circuit. Which is exactly what happened in 1986, when the first Group A 190E rolled onto the DTM grid.

With a machine prepared by AMG, Volker Weilder would win at both the Nurburgring and AVUS circuits, on his way to second in the championship. It was a stellar showing against more established, larger engined opposition and cemented the 190E’s place in the German series.

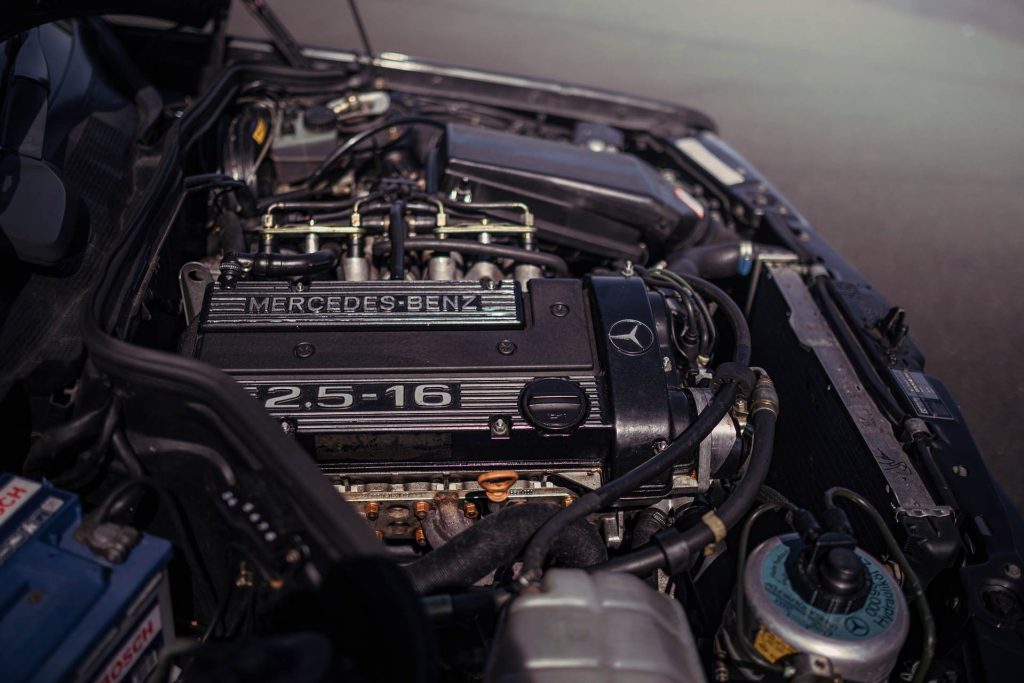

The 190E was updated in 1988 with the capacity increased to 2.5L yielding 204hp for the road car. The extra torque allowed fitment of a taller final drive and, in race trim, teams could extract in excess of 320hp thanks to the large bore, short stroke configuration. But it was the coinciding ‘Evolution’ model that would really begin pushing the 190E to extremes.

Lower, wider, stiffer and more aggressive was the recipe. The 190E 2.6-16 Evolution advanced the concept, with wheelarch flares, a deeper front air dam and skirts, and a larger rear wing in the name of homologation. Not only this but the switch to 16-inch wheels allowed larger brakes and the ability to run a larger wheel on the racer, upping the performance ante for the touring car teams.

In total, 502 examples were built, in line with Group A regulations for evolution versions, ensuring rarity of the roadgoing example.

The Evolution would begin racing part way through the 1989 season and late in 1991 the 190E 2.5-16 would sprout some properly outrageous appendages, heralding the arrival of the Evolution II variant – more of the same, just turned up to 11.

The basic underpinnings remained relatively unchanged, although the 2.5-litre 16-valve Cosworth engine got a power bump to 235hp – and subsequent race engines made in the vicinity of 350hp. Outwardly, the Evolution II felt leagues apart from those initial 2.3-16 models.

With aero designed in conjunction with the Stuttgart University of Technology, the wheelarch flares expanded again, enveloping 17-inch forged six-spoke wheels which allowed even bigger brakes.

The revised front splitter became adjustable, as did the rear wing, offering movable elements both at the top of the structure, and at bootlid level. It creates an imposing aesthetic, and with time has become an icon of the hectic early 90s DTM era.

All bar two of the 502 units built wore the same coat of glimmering Blauschwartz paint, and inside things weren’t too far removed from the original cars. Decked out in tasteful plaid and leather, the deep sports seats hug their occupants, the ideal pew in which to spend a fast run up the autobahn.

A signature Mercedes-Benz four-spoke wheel, albeit smaller diameter, provides the tactile link to the front wheels. While somewhat staid, the dash contains all the essentials, including a tacho featuring a 7700rpm redline.

The driving experience is said to be well rounded, with journalists of the day praising the Evolution II’s ride and roadholding. There was plenty of torque on offer from the 2.5-litre engine, and a willingness to pull to its redline.

The changes would convert to circuit silverware, too. While the Mercedes-Benz team was unable to take out the drivers championship in 1991, thanks to the rampaging Audi, the following year, the 190E would emerge victorious.

With 16 victories out of the 24 races falling to the 190E pilots, it’d be AMG driver Klaus Ludwig who would take the final honours of the years-long Mercedes versus BMW fight, as well as contributing to a hard fought manufacturers championship, and was testament to improvement via evolution. The 190E had really come full circle.

You Spin Me Right Roundel Baby

BMW came to the Group A era with a pile of touring car experience having raced the 3.0 CSL, 2002, and E21 3 Series in the 1970s. The firm hit the ground running with the 635CSi which became a potent force the world over. The dawn of a turbo era and the ageing underpinnings of the 635CSi prompted a rethink and BMW’s M-division needed to create a homologation car for racing.

So began the development of the E30 3 Series. Initially, BMW hastily developed both 323i and 325i versions of the 2-door E30, achieving moderate success. But waiting in the wings, BMW had one of the true icons ready to make a huge splash on the touring car landscape.

BMW’s M-division unveiled its newest offering at the Frankfurt show in 1985, to the approval of the assembled throng. Aptly named the M3, BMW’s new challenger announced its intent loudly. The boxed arches squared up the stance, enabling a wider track and the use of 15×7-inch BBS mesh alloys, critical in permitting bigger wheels on the homologation racers.

Like Mercedes, BMW developed a bespoke aero solution for the M3, epitomised by a deep front air dam and decklid wing, but less noticeable at a glance was the significantly changed bodyshell utilised for the M3. BMW massaged the C-pillar somewhat, creating a shallower angle, which flowed onto a raised bootlid. This reduced the coefficient of drag from 0.38 to 0.33, and the slipperier shape would help considering the M3’s power plant.

BMW made use of its extensive experience with the four-cylinder M10 engine, which was the basis for BMW’s Formula 1 mills. For the M3, the M10 was punched out to 2.3-litres, equipped with a DOHC 16-valve head and christened the S14.

Where it differed from the 190E was the use of individual throttle bodies and electronic injection, offering snappy throttle response and helping the S14 pull cleanly to its 7250rpm redline.

With a peaky 197hp on tap, the M3 utilised a solid-shifting dogleg five-speed Getrag ‘box, with uprated and revised suspension geometry ensuring the car was light on its feet. Brakes were initially lifted from the bigger 5-series and bolted to five-stud hubs. The car was an instant hit, selling considerably more than the planned 5000 production run within six months.

Before the car had even made its racing debut, BMW had ‘evolved’ the M3, with a revised cylinder head, a handful of aerodynamic tweaks and even 16×7.5-inch wheels all combining to create the initial evolution of 505 homologated cars.

When the car hit the track in 1987, it all just clicked. The lithe M3 would edge out the turbocharged Ford opposition, with the Zakspeed entered car of Eric van de Poele taking out top honours. BMW began a landslide of manufacturer championships, the beginning of a reign of dominance that would force the opposition to evolve in order to beat the M3.

BMW was aware of its rivals and in 1988 rolled out the Evolution 2. A bump in compression to 11:1, a more efficient intake and other minor changes improved output to 220hp. A more aggressive splitter hung from the front bumper, and weight savings through thinner glass as well as lighter bumpers and bootlid were achieved.

The ‘88 DTM season proved tougher, with the turbo RS500 Sierras really coming on song, not to mention the ever-improving Mercedes-Benz threat, and the best finishing BMW would be in fourth by season’s end, despite taking the makers gong. In 1989 however, the M3s would come roaring back, perhaps in part to some restriction of the boosted Fords. Roberto Ravaglia would stand atop the podium, despite BMW’s seven race wins to Ford’s eight.

It was during that same year, that the ultimate E30 M3 was being concocted. Named the Sport Evolution, BMW saw fit to punch the S14 engine out to 2.5 litres, fit more aggressive cams and larger valves endowing the road car with a handy 238hp at 7000rpm. With the 2.5-litre at their disposal, BMWs racing partners were extracting over 350hp from the new S14B25 mill, without a turbo in sight.

The chassis came in for some changes, too. The Sport Evo sat 10mm lower, featured sharpened spring and damper rates, as well as geometry changes, all aimed at assisting the race programme. The boxed arches were tweaked in order to accommodate larger 18-inch race wheels.

Production wheels remained at 16×7.5-inches however but, like the 190E Evo II, the M3 Sport Evo sported adjustable front and rear aero, a tangible link to the fire-breathing, spark-throwing racer.

The interior was also special. A suede steering wheel sat front and centre, with a fuss-free, legible cluster offering just the need-to-know info. In the case of our featured car, the Sport Evo also offered a rare Nappa leather option with an M-motif.

BMW would sell 600 units for the three months the car was in production, and while they’d take a manufacturers title in the 1990 DTM season, another driver’s title would prove elusive, with the M3’s touring car racing career ending in 1992 but not before the chassis had become the definitive car of the Group A era, and a darling of the motoring press, revered for its on-road character.

Typically named as the most successful road racing car in history, we’ll leave it to you to decide on your allegiances. The BMW M3, which came in hot and ran consistently, or the Mercedes-Benz 190E Evolution II, an example of persistent development and ultimately the final winner of the Group A era on German soil.