David Dicker – an extraordinary man, an extraordinary vision

Words: Mark Petch | Photos: Dylan Petch

What brings an extremely wealthy Australian tech guru to the backblocks of the south island? Granted, there is a small stream on the western boundary of his 550 hectare north Canterbury farm that might harbour brown trout but there’s certainly no lake, no private golf course, no hint of equestrian activity, no magnificent country estate, rather just a random collection of innocuous sheds of varying sizes and shapes.

On closer inspection there are, however, extensive tar-sealed roads, one in particular running for nearly a kilometre alongside a narrow public access road that forms the inland route between Waiau and Kaikoura. It’s along this road that gobsmacked tourists sometimes get to experience the cacophony of sound as a speeding ‘Formula 1-like’ race car blasts past their vehicles at what must seem like insane speeds on the other side of the farm fence. It’s all that separates the 2.8 kilometre long race track from a normally quiet public road, just 50 metres away.

David Dicker, head of Dicker Data Australia, which recently turned over A$1billion in sales revenue, is certainly not the only rich man to build himself a private race track here, and probably won’t be the last. Such a man could therefore be expected to have a collection of fast toys, and he has them in spades; Ferraris (his favourites), Lamborghinis, and Porsches but few such enthusiasts own a Lotus 125 “F1 customer experience” race car, complete with a screaming 650bhp Cosworth V8 engine. Even fewer have their own 2.8km race track on which to unleash the beast whenever they please. There are actually two tracks at the complex, the original narrow circuit that snakes around and down the river valley, and the full-blown 12-metre wide version which runs in part alongside the long flat paddock that borders the public road.

It would be easy to write David Dicker off as simply another wealthy guy who’s given to excessive behaviour but about that you would be wrong. For everything you see at his property is there for an express purpose, save for his collection of toys, which are mere trappings of his wealth and his love of fast cars.

To even begin to comprehend David Dicker, you first have to understand and appreciate his vision, not easy given the sheer enormity of what he is creating right here in the South Island of New Zealand. Not content with designing and building his Rodin FZERO, which he envisions will be the world’s fastest road racing car, he recently purchased all of the components and commercial rights to the 2011 Lotus 125 project. These were intended to be F1-style customer race cars quite unlike anything else commercially available in the world. Sadly the project never really got off the ground, but five were eventually sold. However, under Dicker’s ownership, Rodin Cars are busy redeveloping these race cars, which will henceforth be known as Rodin FZEDs.

“There is method in my madness,” Dicker explains. “We need a culture of working with F1 technology and the experience my small team of young Kiwi engineers, all ex-Canterbury University graduates, gain from building and maintaining these former Lotus customer ‘F1 cars’ is invaluable.”

They are already getting a ‘hands-on experience’ with the R&D mule and they will develop that car into what it really should have been when it was first envisaged.

“We have had to completely redesign the exhaust system and also the electronics to be able to deliver a reliable F1 experience that our owners will not only be able to enjoy but more importantly be immensely proud to own.”

These Rodin FZED customer race cars will form the vanguard of the Rodin customer experience and will no doubt lead some of these same clients to purchase the ultimate road race car, which Dicker says; “will be faster than anything else in the world, including the latest F1 car.”

While we were not permitted to take any photos of Rodin’s first prototype FZERO car, we did get up close and personal with it, and got to pose some questions for the two engineers who are primarily responsible for constructing the car.

In the flesh, it looks like nothing else we have seen or read about, with enclosed wheels encased in aerodynamic fairings which turn with the front wheels. These blend into soaring fairings for the rear wheels, which are bridged by an enormous rear wing, while there is an equally huge wing up front. With no racing regulations to adhere to, the calculated downforce of the car as a whole is mind-blowing, and without its active suspension, it would be near impossible to drive on the road. Never mind the practicality of this Star Wars-looking vehicle, for it is designed with one thing in mind and that’s to be the fastest road car in the world, bar none.

The driver sits in an enclosed air-conditioned cockpit, equipped with electronically controlled foot pedals, adjustable for both height and reach, while the clutch and shift paddles are operated from the steering wheel. This is made from a combination of sintered titanium and carbon fibre. So far the team has made five different prototypes for the steering wheel in search of absolute perfection. They utilise their state of the art 3D laser printer to manufacture a solid model in a high strength, machinable plastic. The day that we visited, the composite team was putting the finishing touches to the sixth and hopefully final iteration of David’s steering wheel design, which forms the centrepiece of the cockpit and understandably it must be something very special.

So just how can a total engineering staff of 10 people, including Dicker, who does most of the cars concept CAD design himself, design and build this entire car “in house” in the southern foothills of the Kaikoura ranges, some 90 minutes drive north of Christchurch? The short answer is two-fold; a massive investment in cutting-edge technology, plus the dedication of a small group of extraordinarily talented young Kiwi engineers with a “can-do attitude”

An estimated $20million worth of equipment fills the various sheds. In the machine shop proper, there is a trio of CNC machining centres, a CNC wire cutting machine, and a large extremely expensive-looking powdered metal sintering furnace, which can produce complex hollow Titanium components completely unattended. The main building houses David’s upstairs design studio, as well as the engineering department on the ground floor with its neat array of work stations down each side of the room.

Next door to the engineering office are two large, spotlessly clean rooms. One features a ‘Darth Vader-like’ Vapour Deposition chamber, which sits glowing ominously like a giant Dalek that can coat any metal components with pretty much any compound, pure gold if so desired. However, its use at Rodin is to apply a protective coating such as titanium nitride to the surface of the myriad titanium fasteners which are all manufactured in-house from titanium bar stock. From a tiny little 2mm shank, socket head countersunk screw, to suspension bolts, rods, dowel pins, you name it, it’s all made here in a “just in time” W. Edwards Deming philosophy.

There are two large autoclaves on site. One can swallow a whole F1 tub with ease, and a smaller unit is used for less bulky parts. Nestling between these two submarine-like autoclaves is a large nitrogen generator that produces the gas in bulk, which is stored in a large chamber immediately behind the composites room.

At the other end of this long room sits a large enclosed 3D “immersion” printer that had just finished running a perfect solid model of the unique 13×18-inch carbon fibre wheel centre that will of course be made in-house.

Have the composite team made a carbon fibre wheel before, I ask? Answer, no. “But it won’t be a problem. We can model all the various lay-ups we will need to satisfy our strength requirements using our finite element modelling capabilities,” says the team leader.

As if to illustrate their technology and capability, he shows us a carbon fibre end plate for the car’s giant rear wing that incorporates titanium inserts to allow for the rear wing’s DRS (Drag Reduction System). It’s indeed impressive, beautifully made, and it’s no surprise that it fits like a glove into the side plate recess for which it was designed.

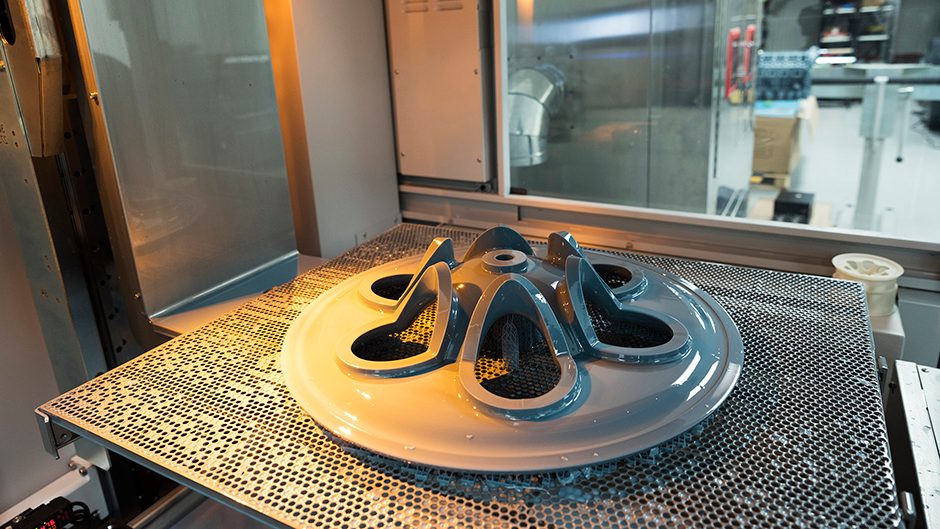

The pièce de résistance of this amazing 3D modelling facility is the full-size model of Rodin’s very own V10 engine which is currently being built in England by ex-Cosworth engineers who now work for Rodin Engines UK. The super compact 4.0-litre V10 engine features the very latest Mahle direct injection piston technology. This incorporates a pre-chamber that compresses a partially exploded charge into the main piston bowl, much like a diesel engine, producing more efficient combustion than a conventional Otto cycle engine.

The compact 72-degree vee engine layout allows for an almost perfect downdraft inlet port and a correspondingly excellent exhaust port design, all of which should produce 700bhp from a naturally aspirated engine. The ultimate FZed “Plus” car will feature a turbocharged variation of the same basic engine that will produce in excess of 1000bhp. And what about the transmission? The internals are being produced by Ricardo in Italy, and will be then fitted to the carbon fibre gearbox housing that forms the rear section of the main monocoque.

The car’s main monocoque and gearbox housing are the only parts of the prototype car that have been built by outside contractors. However, in future these comparatively large composite structures will be built in-house when production of the first five cars commences. It’s obvious that the workforce needed to produce the first five cars will have to grow. However Dicker is confident that when the time comes to build the first batch of cars in 2019 there will be enough skilled composite workers available here in New Zealand, given the extended date of the next America’s Cup challenge. The technology is no different in high tech America’s Cup yachts to a current F1 car, and Kiwis lead the world in that discipline Dicker says. “If we can attract the right people at that time we will do pretty much everything in-house which is, after all, my philosophy and objective for Rodin Cars.”

Why choose New Zealand as a base? “Well, when I started to think about about it, there are not many countries that I would be happy to live in, and that would also allow somebody like myself to set up such a facility as this.” As you have seen and experienced, we have built a 2.8km, 10-metre wide race track with no town planning and noise consent dramas. That includes trackside pits and service bays. Where else could you do this at anything like the cost? It would be near impossible in my native Australia, prohibitive in Europe. And then there is this pool of extraordinarily talented young Kiwi engineers graduating out of the Canterbury University that would be mostly lost to New Zealand and so the more I thought about it, the more New Zealand just made perfect sense.”

When all the trackside facilities and landscaping are finished by early 2018, it will be a magnificent facility for owners of the cars to fly into. “I want to create a facility much like Ferrari’s famous Fiorano test track, right here in the alpine valleys of the Kaikoura ranges. Aside from driving their very own race cars pretty much whenever they want to, there is also so much to see and do within less than an hour’s flying of our facility that will captivate our customers and make them want to return to New Zealand time and time again,” says Dicker. “I have houses in Australia, Dubai and Italy, and for the moment I am living in the old farm house until I design and build something more appropriate. It’s my choice, as I spend most of my time up here in my studio living, breathing and creating my dream, and need little more than a warm bed when I need to sleep.

Why the name Rodin I ask? Dicker smiles and poses like Auguste Rodin’s most famous statue “The Thinker”. How very appropriate. Early next year we will head back to check on the progress of Rodin Cars, so look for the next instalment in 2018.