1978 Ferrari 308GTB

Words Richard Opie | Photos Richard Opie

We’ve all got ‘the one.’ the car of our dreams, often the one first pinned to our bedroom walls. But how does the dream measure up three decades later?

I’ve never had to start a story with a disclaimer before. However, the moment that little Facebook Messenger window popped up on the desktop the intro to this yarn was set in stone. “Hey, we’ve got this 308 here we’d like a few shots of,” read the little blue speech bubble from Aidan Barrett. “Oh, and you can take it for a drive.” I suppose some context is necessary. Barret is the custodian of a pretty special RX-7 racer ex-Japan, and our acquaintance came about through mutual attendance at an event were he was turning demo laps at the helm of the rotary rocket.

At some point our conversation turned to Ferrari’s 308, and my reverence for the Pininfarina-penned silhouette. While the Countach and Porsche’s 930 often dominated discussions among my peers during formative years, I only had eyes for the 308 GTB. That was the dream car that adorned my bedroom wall. A huge cutaway poster clung stubbornly to the gib courtesy of four brass tacks. To be exact, it was the 308 QV, and I practised the pronunciation of ‘Quattrovalvole’ repeatedly. It’s probably something I never quite mastered. That poster of the 308 GTB QV, with all of the interesting mechanical bits on display, lasted until the UV streaming through the windows stole its vibrance and detail.

So yes, the 308 is my hero car, and there’s that cliché about staying away from them. There’s something about the inevitable disappointment but over 30 years on – thirty – here I was with the opportunity to experience just that. But first, a little bit of history on how the 308 GTB and its roof-optional stablemate, the 308 GTS came to be. The 308 story really begins with the development of the Dino 206 GT. Born of a Pininfarina-penned 1965 prototype and rolling out of showrooms in 1968, the Dino marked a distinct evolution for Ferrari road cars.

For one, the engine was mounted transversely behind the driver, at odds with Ferrari’s then front-engined, rear-wheel drive convention. Secondly, the 2.0-litre engine comprised just six cylinders, another first for a Ferrari road car. And third, the Dino did away with Ferrari badging altogether, instead forging its own path as a cheaper sub-brand aimed at poaching the popular Porsche 911’s market share. Although the Dino 206 GT and the later, more powerful 246 GT weren’t bad cars by any stretch, they met with their share of derision. The break from tradition under a new branding prompted some “not a real Ferrari” sentiment, which by now is long overturned.

Ultimately, the Dino morphed into the 308, although those three digits initially came attached to the rear panel of a 2+2, the 308 GT4. In 1973 the 308 GT4 again introduced deviation from the norm. The swoopy sixties styling gave way to the angular lines of the Bertone design which attempted to cash in on the wedge trend kick-started by Giorgetto Giugiario. The Dino badge remained, but the 308 GT4 added a pair of cylinders with a 3.0-litre Type F106 V8 resting at ear level behind the rear seat occupants.

All alloy, with a flat-plane crank and double overhead cams, the F106 announced Ferrari’s foray into eight-cylinder cars, in essence providing the genesis for a lineage that continues to this day. While the GT4 attained ‘proper’ Ferrari status in May 1976, casting aside the Dino badging, it’s oblique lines never gained true favour, and in 1975 Pininfarina was back as the chosen styling house for Ferrari’s newest entry-level two-seater.

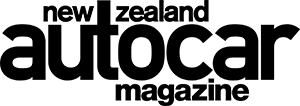

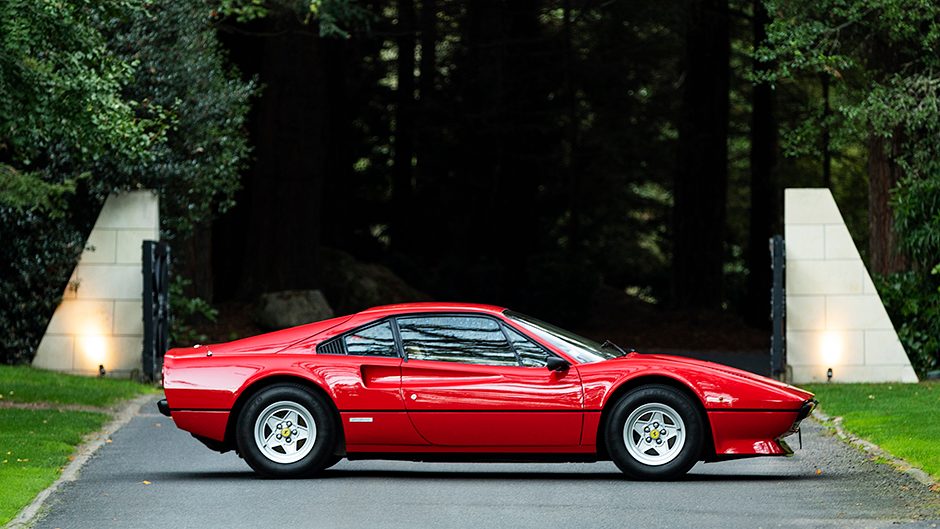

First shown off at the 1975 Paris Motor Show, the early 308 GTB displayed the beautifully flowing proportions so characteristic of the Dino 206/246 GT, but sharpened for the seventies. From a chopped off Kamm tail rear, the flowing waistline kicked over the wheel arches and terminated in a shark-nosed front profile. The cabin is set low between the arches, the driver peering over a sloping bonnet from which headlights pop up on demand, and deep side air intakes draw much more in common with the high-end 512 BB stablemate than the GT4. What mattered was the perception that the 308 GTB was every inch a Ferrari.

Early cars featured fibreglass bodywork constructed over a tubular frame for a kerb weight of 1050kg. The dry-sumped, transversely-mounted 3.0-litre pumped out 255hp (190kW) in its European specification, breathing through a quartet of downdraft Webers. In standard Ferrari fashion the short block was of all-alloy construction, with belt driven cams carried over from the GT4.

This was seen as a maintenance friendly option when compared with a chain but the 90-degree V angle did make accessing the front facing bank a tricky prospect. However, for the owner of a then-new 308 GTB that was likely the dealer’s problem. The power level may have been modest (and even more so if you were unlucky enough to be a USA customer with some 15hp less), but it was enough to see the featherweight Ferrari sprint from a standstill to 100km/h in less than seven seconds. For 1977, the fibreglass shell yielded to steel bodywork and a weight increase, and a year later the 308 GTS joined the line-up.

Made famous by the fabulously-moustached Tom Selleck in Magnum P.I., the GTS offered open air motoring for the mid-engined Ferrari enthusiast without compromising the snappy handling introduced by the Dino 206 GT. In fact, in period the 308 was praised for its sure footedness, especially when compared with the tail-heavy Porsche competition. Predictable and safe were attributes commonly bestowed on the Ferrari by the motoring press, with a tendency to shift weight smoothly and not bite back when the pilot backed off mid-corner. Later generations saw the addition of fuel injection but also more emissions control and less power with the 308 GTBi rated at 211hp (157kW) in Europe.

In an effort to regain the lost horses, four-valve heads were added in 1982 bumping power back up to 240hp (179kW). It was never quite the performer of the early cars but production carried through until 1985 when it was replaced by the 328 GTB/GTS. It’s worth noting the 308 GTB provided the base for Ferrari’s first supercar, the twin-turbo 288 GTO introduced in 1984 as a pursuit of Group B race glory. But I digress.

On arrival to the Barrett family’s Taupo workshop, John Barrett Motors, the immediate greeting was the scarlet silhouette of their 1978 308 GTB. And it’s one of the good ones, a full-fat 240hp carb-fed UK-spec model that’s been a member of the family for some decades. It was originally owned by an uncle who worked offshore as an aircraft engineer, allowing him to indulge in a penchant for exotic machinery.

Before the Ferrari there was a Porsche 911 2.7, but in the late nineties, the Rosso Chiaro-coated example found itself on NZ shores, replacing the Porsche and serving as a very occasional driver during visits back home. The car has since seen little work on New Zealand roads, with about 1500 miles added to the Veglia odometer in the past 20 years.

Sadly, the original Kiwi owner passed on, leaving the car to his brother, John, who now cares for the immaculate V8 icon, with the occasional drive thrown in to keep the cogs oiled. Taking stock of the styling is a task for minutes, not seconds. The design purity of these early cars is undeniable, particularly in European spec, devoid of the USA’s gargantuan 5mph impact bumpers. A combination of crisp edges and radiused curves, punctuated by slatted vents aft of the headlamps, and atop the engine lid.

Appreciating style that’s endured through the decades with dignity is one thing, but did the driving experience echo Pininfarina’s pen strokes? In the past, a younger version of myself would have expected a performance sucker-punch and my opinion may have been negative. The 308 isn’t a fast car by today’s standards but as it gathers speed that flat-plane V8 sings a glorious, almost elegant induction tune. The overriding sensation is that of appreciating a complex musical composition.

The 308 offers a tangible experience; it’s less a flashy supercar and more a finely crafted driving tool. You dissect the experience, eliciting joy with each little discovery. The unassisted steering spoils the driver. Every pebble, corrugation and undulation is amplified through the Momo steering wheel with its wondrous patina. But you’re at the mercy of that uniquely Italian driving position, designed for short legged, long armed folk. The clutch is heavy, and a curbside departure requires a bit of a fumble into the dog-leg first gear, left and down on the gated shifter, now sadly lost to modern Prancing Horses.

For the enthusiastic newbie, the shifter is an awkward thing to come to grips with, especially when cold. As the oils warm, shifting becomes an experience of its own. It makes a satisfying click, as the shifter hits home at each notch. The revs drop, then build seamlessly again as the right pedal is buried, revving smoothly to a 7500rpm redline. Somehow the ergonomic nightmare of the cabin becomes irrelevant. Operating the ventilation controls on the move is distracting, fit for an instant $150 fine, the headlights are mighty confusing and headroom is at a premium for the lanky.

The way the Ferrari dances across the tarmac on the meaty 14-inch tyres distracts from all of that though. Cornering feels safe, surefooted. While I didn’t push the limits it felt like it could be hustled with composure and confidence. The brake pedal needs a dedicated shove, but nonetheless it’s rewardingly communicative.

It was an experience that I wanted to continue for hundreds more kilometres in search of the ultimate driving roads, while growing a bushy moustache. The kind of journey the 308 GTB was crafted for. Like the poster on the wall, the experience has passed. But unlike that raggedy old cutaway illustration, the details will remain pinpoint and crystal clear.

Thanks to Aidan, John and the wonders of modern communication, I was able to deduce that heroes should absolutely be met, and you should get to know them intimately, especially on a great stretch of tarmac.