As the curtain fell on the 1986 Australian Touring Car Championship (ATCC), the thoughts racing through the mind of tin-top legend, Dick Johnson, must have been bittersweet. The Group A formula had replaced Australia’s homebrewed Group C rules a couple of years earlier, and Johnson was without a suitable steed in the wake of Ford Australia’s refusal to homologate the Falcon. Instead, his team struggled with the dependable but uncompetitive Zakspeed-built Mustang against the likes of the Volvo 240T, BMW 635CSi and Skyline RS Turbo.

But Tricky Dicky was always up for a challenge. He was the hard-charging people’s champ who came back from near ruin following the 1980 ‘Rock’ incident to take a championship. His saviour was coming in the form of Ford’s four-pot turbocharged terror, the Sierra RS Cosworth. Poised to set the Group A world on fire, (literally, thanks to the trademark flaming side-exit exhaust) the Sierra would become the benchmark in Dick’s hands.

Because none would be more dominant than the Sierras DJR built, earning the tag of ‘world’s fastest,’ eclipsing even the efforts of Eggenberger and Rouse, the powerhouse teams of the European touring car circus, on their own turf. It’s a feat Dick himself is incredibly proud of and while the Sierra RS Cosworth legend is well known, the journey was anything but easy.

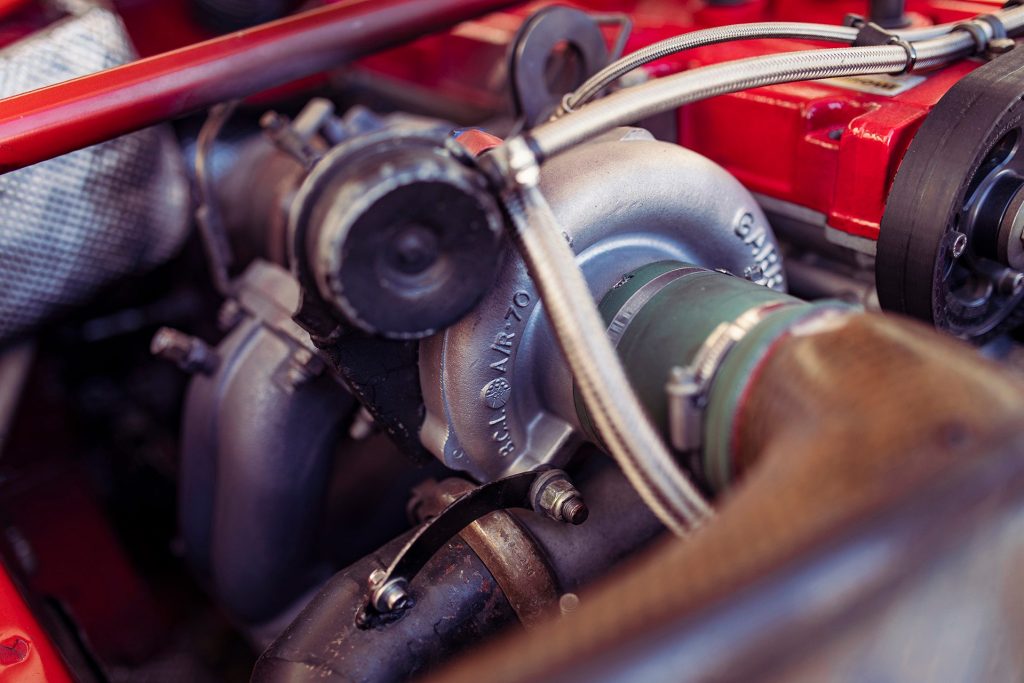

Launched at the Geneva show in 1985, and offered for sale from July 1986, the RS Cosworth was intended to make Ford competitive again in touring cars. Mandated by Ford Europe’s head of motorsport, Stuart Turner, a deal with Cosworth culminated in a twin-cam variant of the tried and tested 2.0-litre Pinto engine, with a comparatively small Garrett T03 turbocharger hanging off the side of the head. Allied to the aerodynamic, rear-wheel drive Sierra hatch platform, the sum of the parts had potential to be a winner.

European teams began development immediately with Ruedi Eggenberger and Andy Rouse spearheading the charge. With a fresh naming rights sponsor in the shape of Shell, Johnson also embarked on construction of a pair of Sierras in Australia, christened DJR1 and 2. With a shopping list of parts acquired from Rouse’s team, Johnson’s two-car team hit the Aussie tarmac at Calder Park. It immediately became apparent that the Sierra was a fragile and difficult-to-manage proposition, with just a solitary win in Adelaide. Also proving a problem was the support from Rouse in Europe.

Drivelines turned out to be weak, the Getrag gearbox regularly offering a selection of neutrals and the turbos were a consumable item. Johnson reckons the team blew through as many as 37 turbos in 1987 alone, but the real sticking point was the engine management.

Rouse held the trump cards when it came to

programming changes to the Cosworth engine’s Zytek computer. Johnson flew to the UK to ask Rouse if he could secure the equipment to do the same himself, to which

Rouse was vehemently opposed. That was the turning point, the pivotal moment when the DJR Sierras would begin their transformation into being the world’s quickest. Johnson himself admits he wasn’t sure which direction to go, after he “told Rouse what he could do with his stuff,” but with the advent of the RS500 evolution model of the Sierra Cosworth later in the 1987 season, it all began to click.

With the RS500 came more performance and also more reliability, at least where the engine was concerned. Ford produced the necessary 500 evolution models to homologate the larger turbocharger, bigger intercooler and stronger engine components while some subtle tweaks to the aero package kept the slippery Sierras planted. Add to this DJR’s locally-developed Bosch engine management packages and the team was on the way to getting a handle on the feisty hatchbacks.

But not before an “embarrassing” Bathurst in 1987 (also a round of the 1987 WTCC). Both cars fell by the wayside within four laps, with the European heavyweights steaming ahead.

Johnson enlisted the expertise of Aussie firms to develop and homologate (with the assistance of Ford UK’s John Griffiths) driveline components like a new diff (Harrop) and six-speed gearbox (Holinger). Despite Johnson’s frosty outlook on the European teams, Ford still wanted to see the Sierra winning, regardless of where it raced. And Johnson freely acknowledged Ford UK’s assistance in pushing through changes with the FIA.

In 1988, the success came in spades. The bright red Shell Sierras took 1-2 in the ATCC that year, winning every round bar one, with Johnson behind the wheel of a new car, DJR3 and freshly minted team-mate, John Bowe, seated in the original DJR1. So confident in the performance of the Sierras was Johnson that he made the call to challenge Europe’s best, on their home turf.

The “world’s fastest Sierras” legend was born at Silverstone in September of 1988. DJR3 made the 15,000km journey to the penultimate round of the European Touring Car Championship (ETCC). The ‘redback’ Sierra proved its mettle, besting the field by over four tenths of a second in qualifying, and disappeared from the Rouse, Eggenberger and other favoured opponents during the first stint of the race. Bowe strapped in after the first stop and was cutting a swift swathe through traffic before cooling system woes forced the car to pit, ultimately relegating the DJR duo to a 21st place finish. Nonetheless the point was proven.

The 1989 ATCC was a case of déjà vu, with Johnson and Bowe again taking out the first two positions on the table. The elusive Bathurst win also came to the pairing, leading every single lap on the way to a victory over a grid dripping with quality, at the wheel of the fifth Sierra chassis developed by DJR. It was arguably the high point of the DJR Sierra, three seasons deep into developing a world-class contender.

By 1990 things got a bit trickier for the Shell Sierras, not helped by the arrival of the Skyline GT-R. In 1992 the rulebook had squeezed the turbo-powered cars even further, increasing the minimum weight and restricting the available engine speeds. In 1991, the team went winless, and in 1992, the final year of Group A competition in Australia, the Sierra bowed out in somewhat controversial style. The Bathurst 1000 was shortened due to horrific conditions, and the Sierra was awarded second place while many of the fans (who Gentleman Jim called ‘arseholes’) believed the car ought to have won.

These Sierras occupy a special place for motorsport fans down under and in recent years many have returned to prominence both in collections and on track, subject to restoration back to their Group A glory.

For Cantabrian, Lance Coupland, who is the current custodian of DJR6 (the final chassis to come out of the Dick Johnson Racing stable), acquisition of the Sierra is the culmination of a decades-long fascination with the cars. The fact that his pride and joy is able to get out and run with the Historic Touring Car (HTC) group is an added bonus, enabling fans to get up close and personal with a fair-dinkum example of DJR’s handiwork.

Lance is the first to admit that the prospect of steering a firecracker like an RS500 is somewhat daunting. “I dabbled a little bit in the early 90s in my Laser TX3,” Lance recounts. “I went out to a driver training day, had a go, and found myself in a bit of a race at the end! It was exhilarating to say the least!” The TX3 remained the extent of his racing endeavours, until a chance visit to Skope Classic in 2020 re-ignited the flame.

“I’ve always loved the Sierras,” Lance explains, “and after seeing the HTC group, I figured if I was going to do this, I wanted to do it with an RS500. It’s the one and only dream car, really.”

The fascination goes right back to the 1990s, and even as specific as the DJR cars. Lance was present that gloomy afternoon in 1992 when Group A came to an end at Bathurst, and with it the culmination of DJR’s six-year Sierra campaign. But the mystique of the potent small Fords stuck with him.

“They’re 1993cc, and pump out something like 680 horses with the boost turned up. How the hell can they do that?” smiles Lance.

Lance contacted the Bowden family, a prominent name in classic race cars over in Australia, asking if they could help him source an RS500. Three options came back, and one of those was DJR6, a car Lance had last come across while hunkering down in torrential rain at Mount Panorama in ‘92.

The car was ready to run, with a recent restoration and an Australian Heritage Touring Car championship under its belt, perfect for a debut at the 2021 edition of Skope Classic. But Lance wasn’t quite ready to strap himself into the hot seat, instead recruiting the capable hands of Greg Murphy to display DJR6’s credentials to the crowd. It’s theatre, with undeniable appeal. Loads of corner exit opposite lock, screaming, popping and flaming from the side-exhaust and DJR6 danced to four out of four race wins over the weekend, setting pole and engaging in some enthralling early lap battles with Stu Rogers’ GT-R. Murph reckoned the car was knocking on 260km/h coming to the end of the main straight, testament to the straight line pace of the boosted Cosworth mill.

As for Lance himself having a steer? “Well, I’m tentatively easing into it,” he says, after explaining the quickest thing he’s driven in recent years is a Ranger ute. He likens the Sierra’s temperament to a well mannered but wild animal. Under braking, and through the corners the car has plenty of grip, but conversely Lance mentions, “it’s got so much grunt, you really have to respect that throttle!”

“It’s another level from any other racing I’ve done, so I’m doing a bit of driver training to get my head around it. I’ve had a couple of moments, a bit of a tank-slapper, but I managed to untangle it,” Lance laughs.

“It’s great to have a pro driver like Greg behind the wheel, to really take it to its limits and show what it can do,” he says, “but I won’t be doing that when I’m driving it. It puts a smile on your face though. I enjoy it but I have a healthy respect for it!”

While the DJR Sierras may have enjoyed a mere six-year tenure at their competitive peak, their star isn’t extinguished. Coupland’s enthusiasm to run the car among the HTC group means a part of the legend will live on.