Formula 5000: Some admire art – We race it.

Words Richard Opie | Photos Richard Opie

Formula 5000 racing has long enriched the fabric of top-level kiwi competition and it’s now the pinnacle of historic racing here. We take a look at the recent NZFMR field and profile a few of the best.

A celebration of all things quick and historic, the New Zealand Festival of Motor Racing (NZFMR) represents one of the most important nostalgic meets over the summer season. The festival has alternated between celebrating a marque or a personality and for 2017, Ken Smith’s lifelong race career was the focus.

Along with Ken Smith, there’s been another constant throughout the eight years of NZFMR. The SAS Autoparts MSC NZ F5000 Tasman Cup Revival series has captivated crowds with the apocalyptic thunder of a field of the best F5000 cars in the world. Since its inception in 2003/04, the presence of a full grid of 5.0-litre V8-powered, slick-shod monsters hitting the loud pedal has remained one of the jewels in the crown of Kiwi historic racing.

The premise behind Formula 5000 was simple. Near Formula One performance on a budget. All cars in period ran stock iron blocks (predominantly Chevrolet), with heads restricted to 23-degree valve angles. The category spread worldwide, with USA, UK, Australia and NZ among others embracing the class. Drivers flocked to the 5000s, with locals Graeme McRae, Graeme Lawrence and David Oxton making a name at the helm of the big bangers. Internationally, names like Redman, Scheckter, Posey and Pilette all found success in the F5000s. Kiwi manufacturers also came of age during the F5000 period. Alongside big names like Lola and March, Kiwi creations like the McRae and Begg found success on the tarmac.

The F5000 Association came about through an increasing number of cars running in what was then a Formula Libre class. In 2003, a subgroup of this organisation created the first F5000-only grid, with 12-15 cars fronting for the first season. Those days, most of the cars came from the US where F5000 was especially prevalent, but now several chassis from the original New Zealand series have been restored and take to the grids and now 40 cars are registered with the class.

The beauty of F5000 as a historic series lies in attainability. While not strictly cheap, cars of provenance are more affordable to not only buy than an equivalent era F1 or Indy car, but owing to their stock-block V8 rules, they’re cheaper to run. A small industry has emerged to support the racers, with the likes of John Crawford in Christchurch engineering hubs and suspension components, and Arrow Wheels making rolling stock.

Each car on the grid has real history, none are replicas and all run under a certificate of description (COD) to ensure period specification. Testament to this is the fact Ken Smith’s laptimes around Manfeild (the only track that remains as per period) are basically unchanged since 1976.

As long as the major historic events continue, the F5000 series should continue to prosper, leaving spectator jaws dropped and ears covered.

1975 Lola T332 – Alan Dunkley

The Lola T332 is viewed as one of the ultimate Formula 5000’s. Combining the formidable T332 monocoque with one of the F5000 Association’s youngest and fastest wheelmen was always going to prove a spectacle. At 27 years of age, Alan Dunkley may be half as old as many of the series’ regular drivers but with this comes a burgeoning natural talent and quite likely, the exuberance of youth.

With an upbringing amongst historic race cars and groundwork in karting from the age of six (alongside a certain Hartley and Bamber) the transition into a more serious car was inevitable. The T332 isn’t Alan’s first Formula 5000 rodeo however. In 2012, he took to the tracks in a high-winged 1968 Lola T140, one of the first iterations of a Formula 5000. The T140, as Alan puts it, was a pretty basic sort of a beast. Running a wet-sumped 5.0-litre Chevrolet, front radiator and rudimentary aero, the T140 was severely down on power on debut in 2012. The following season, the Dunkley team added alloy heads, boosted the power of the engine and added all important lightness to the chassis. The result? Alan took out the Class A (pre 1971) honours for the 2013 season.

This current car, adorned in the livery of Ted Field’s Interscope Racing began life in 1975. Supplied to Interscope as a bare tub, the T332’s intent was largely to supersede an upgraded but increasingly uncompetitive Lola T400. The mechanicals from a previously crashed Interscope T332 (chassis HU42) were applied to the new monocoque, and American Danny Ongais climbed aboard for what would be only three races. Following rounds at the Long Beach and Road Atlanta circuits, Ongais unfortunately damaged the car at Riverside, proving to be the T332’s final race.

Sponsor and wreck collector Ed O’Brien subsequently held on to the tub until 2005 when it was spirited across to New Zealand shores by Shayne Windleburn. Eventually reskinned and built up to a complete car bearing the chassis number HU42/2, historic racing stalwart Roger Williams settled into the cockpit and competed extensively throughout New Zealand and abroad in F5000 races. Nowadays, under the ownership of Stuart Lush, the car is looking and performing better than ever thanks to further restoration and development.

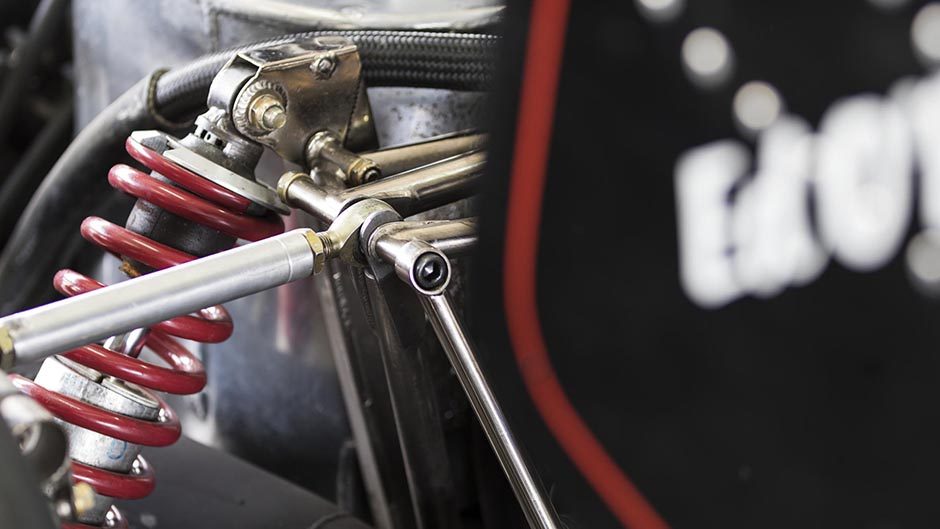

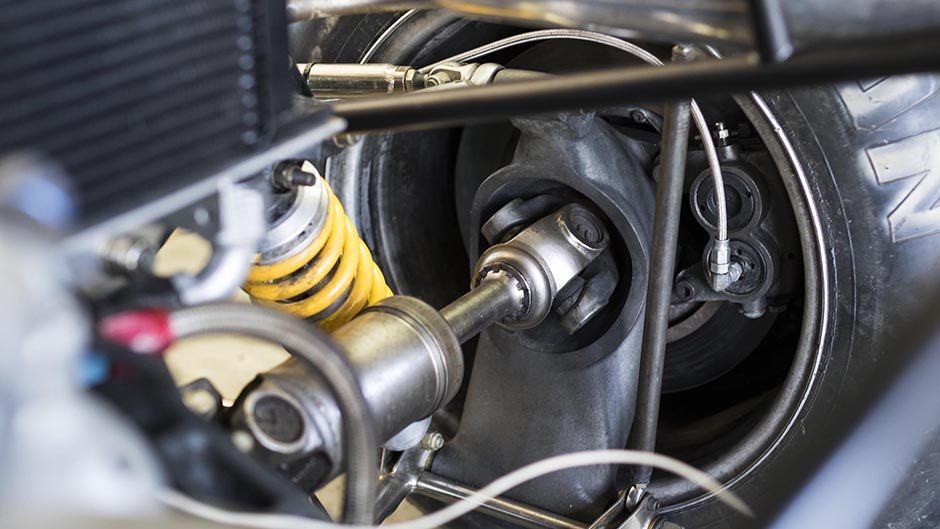

Alan describes the T332 as much more of a precision instrument when compared to his old T140. With far more developed aerodynamics, and lower mounted, dry-sumped Chevrolet, the handling in particular is more befitting of a ‘wings and slicks’ racer. Whereas the old T140 could be chucked sideways, sliding around corners, the T332 requires a deft touch – not an easy task with the heavy, analogue way these cars behave courtesy of their gargantuan slick tyres.

Nonetheless Dunkley was on the pace, qualifying second to the old fox himself, Ken Smith and even managing to keep his nose in front of the veteran for a couple of laps in the opening F5000 race of the NZFMR.

1975 Lola T332 – Ken Smith

There aren’t too many drivers at an historic race meeting who can say they’re driving the same car they did in period. Even fewer continue to stand on the top step of the podium, amongst equally stiff competition now as they were 20, 30 or 40 years ago.

The NZFMR for 2017 celebrated Kiwi single-seater expert, Ken Smith. A man who even though he’s firmly in his mid-70’s still straps into the confines of his 1976 Lola T332’s tub. Then he proceeds, somehow, to go out onto the track and win with freakish regularity. If he’s not doing that, he’s running in the top three and pushing hard – a foray at last year’s Philip Island Classic featured Kenny running with the leading pack, and finishing second and third for the weekend’s races.

But he’s still in the same car; well, sort of. The T332 that Smith has campaigned in historic Formula 5000 racing may resemble his 1975/76 New Zealand Gold Star drivers’ championship winning car, but it is in fact a faithful reproduction. The original is stowed safely away in Australia.

Both Smith’s and Dunkley’s cars have origins with the USA-based Interscope Racing squad. Not only this, but both their cars were initially punted by Danny Ongais. Formula 5000 historians surmise that chassis HU54, the number borne by Smith’s current steed, was in fact purchased by Interscope to replace a previously damaged T332, which is coincidentally the car now piloted by Dunkley.

Whatever the specifics, what is known is that Ken’s car languished in the Justice Brothers Museum in California. Donated by Ed O’Brien to the collection some time during the late 1970’s, Lola T332 chassis HU54 sat on display for over 30 years. In 2010, Smith acquired the car.

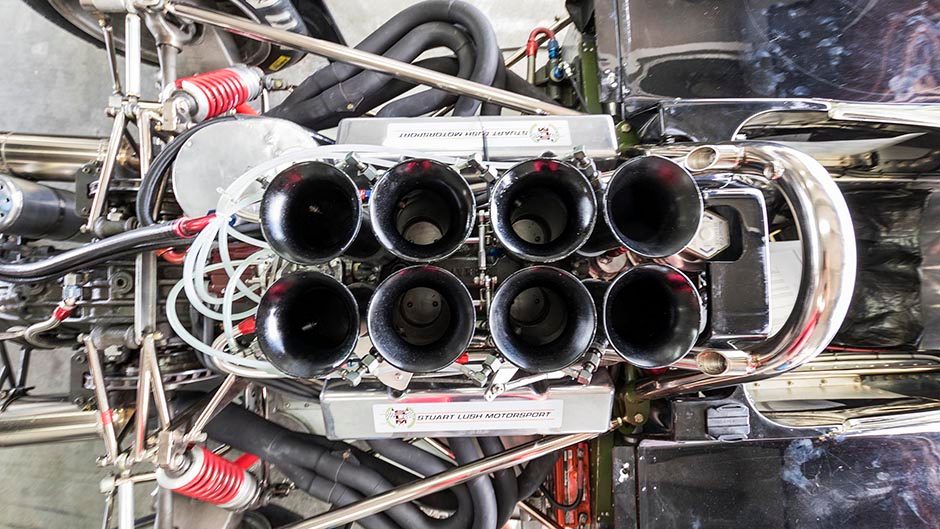

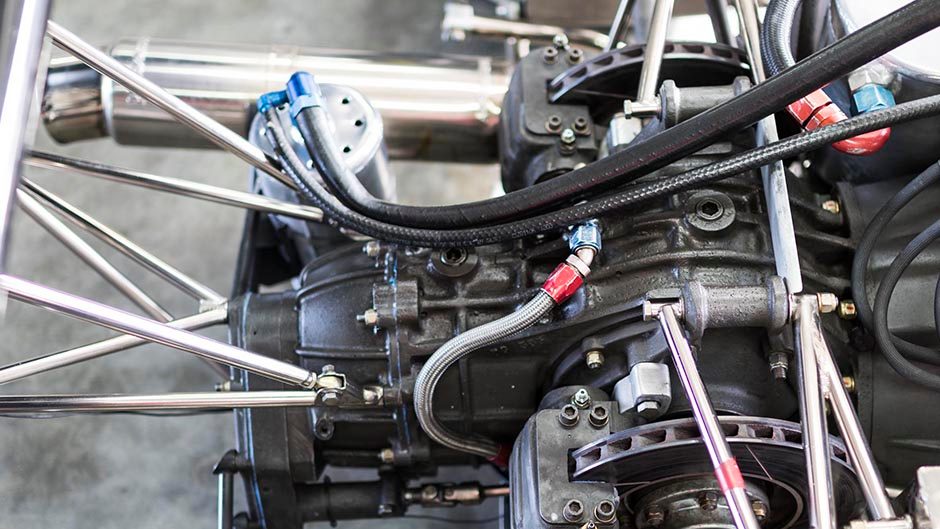

Smith and his team have upgraded the car to T332C specification, notable by the single-post rear wing. Eschewing the original black-with-orange livery that rendered the Interscope cars so distinctive, Ken’s car now sports the famous scarlet hue as seen for this successful 1975 season. Adorned with the familiar La Valise Travel signage and his trademark number 11, the Lola is among the most meticulously prepared with glistening nickel-plated suspension components framing the mechanically injected 5.0-litre Chevrolet engine.

With the Camaro V8 pumping out over 550bhp and a dry weight of just over 625kg, Ken demonstrates with remarkable effect just why the T332 was the most revered machine of this thundering period. With a 2017 NZFMR clean sweep to add to his trophy cabinet, you can’t help but wonder what it’s going to take to knock “King Kenny” off his local Formula 5000 throne.

1970 McLaren M10B – Frank Karl

Without mentioning a McLaren, would a story about Formula 5000 racing in a Kiwi context be complete? Frank Karl took the time to talk us through the history and restoration of his 1970 McLaren M10B.

As the oldest car on the grid, the M10B stands out by pure virtue of its “cigar body” aesthetic. More reminiscent of a 1960’s Formula One car, the M10B provides a stark and elegant contrast to the later “wedge” profiled cars such as the Talon and later model Lolas.

The M10B was an evolution of the initial McLaren F5000 contender, the M10A of 1969, which itself was a development of the M7 Formula One chassis, featuring a more rigid but larger and heavier monocoque section. With a 5.0-litre V8 slung behind the driver the M10A was identifiable by its towering rear wing. With the advent of the M10B, the tall rear wing disappeared in favour of a low mount set-up while the engine plate to the rear of the tub allowed a dry-sumped engine to sit lower for imp

Frank’s M10B, a car built by UK constructor Trojan, began its competition life in 1970. Purchased by British team owner Alan McKechnie, the car spent three seasons racing in the UK with Mike Walker. Following its British career, the M10B chassis 400-18S found itself destined for the heat of South Africa.

Race engineer and Formula 5000 extraordinaire, Duncan Fox purchased the tub in 2002, before current owner Karl made the call in 2004 to purchase the M10B and restoration began in earnest. He openly admits that much of the impetus to seat himself behind the wheel of the McLaren was somewhat emotive, that “Kiwi pride” of piloting the M10 is surely tough to beat.

Although one could argue the only colour for a period McLaren is ‘papaya,’ the McKechnie racing livery of green and gold plays out in period perfection along the svelte tub. Slung from the back is the requisite 5.0-litre Chevrolet, however this engine isn’t topped by towering injection stacks. Instead, Karl’s Chev breathes through a quartet of Weber IDA carbs, just like it did in 1970.

Only recently, Karl and the M10B survived a fire while racing at Barbagello, in Perth. A banjo bolt on the carbs vibrated loose, spraying fuel on the hot exhaust headers. Karl noted the flames and pulled to the side, but not before the flaming jet of fuel shot down one of his gloves and burned his hand. Otherwise okay, the attention turned to the M10. Extinguished before total loss, basically anything combustible behind the bulkhead required restoring to make the NZFMR grid. The M10’s paint still bears the scars of the flames, but as Frank explains the car is built for racing; battle scars are a mere indicator of the true purpose of Bruce McLaren’s 1970 creation.