Driving a Ferrari 612 Scaglietti across China

Words: Mark Petch | Photos: Supplied

We fly to China and journey to Tibet and back in the most unlikely of mud-pluggers, the new 612 Scaglietti from Ferrari

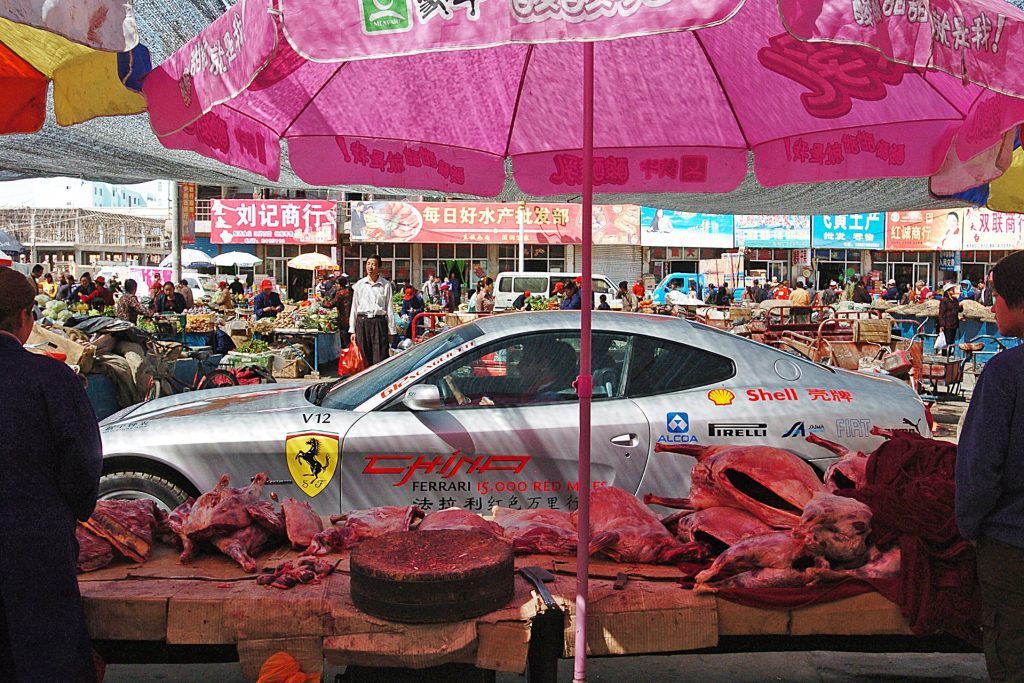

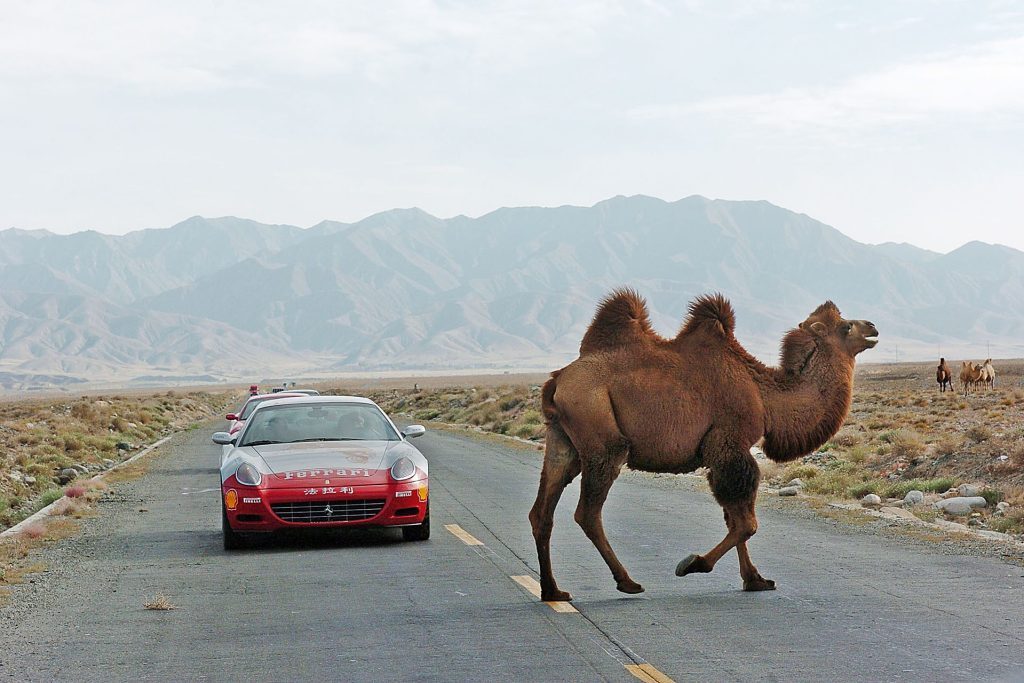

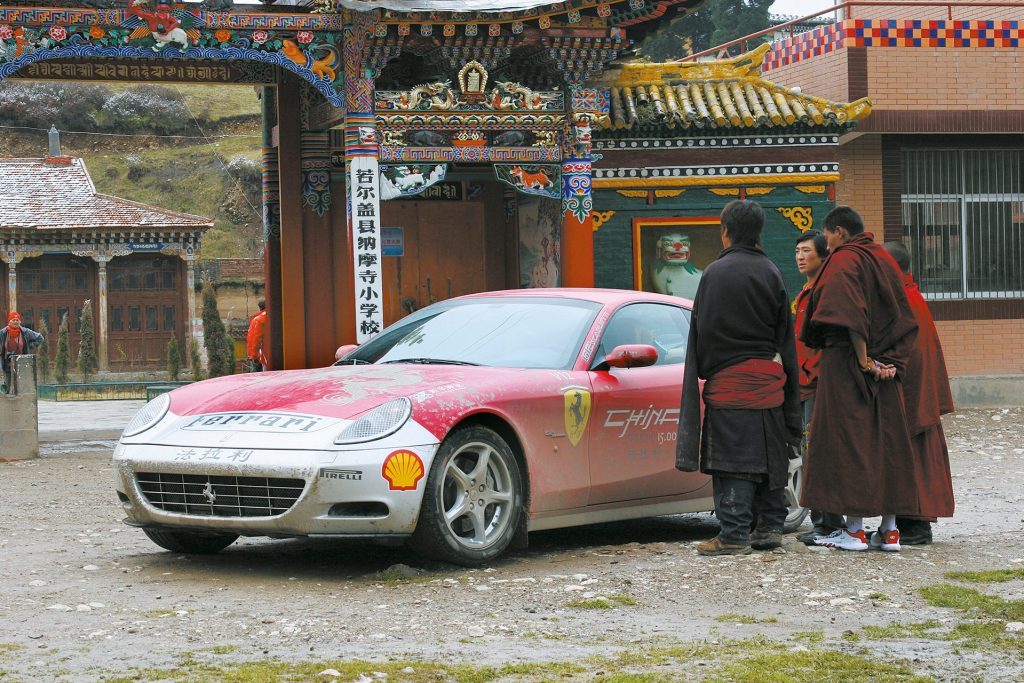

Brickbats or bouquets? If the idea of taking a pair of half-million-dollar 550-horsepower V12 supercars to explore China seems absurd to you, then think how bizarre it must have looked to the inhabitants of one of the world’s oldest civilizations.

Marco Polo journeyed east through vast and dangerous lands to reopen the trade route to China in AD 1271, and along the Silk Road nothing much has changed in the hinterland of China since his mule train passed that way more than 700 years ago. Inspired by history, Ferrari decided to emulate the feats of the audacious explorer, and extended invitations to 15 international motoring writers, myself included, to join them in a ‘mission impossible’ lasting 45 days, with each of the journos participating for up to seven days at a time. My colleague for our planned seven-day segment of the 15,000 Red Mile Ferrari tour was fortunately a fellow Antipodean scribbler, Bob Jennings, from the Sydney Morning Herald. I say ‘fortunately’ because not only is Bob an old colleague of mine, he also makes a great travelling companion. And ‘fortunately’ because, at various times, it was bloody hard work accompanying a group of Chinese and Italians who, apart from the PR manager for Ferrari, spoke very little English.

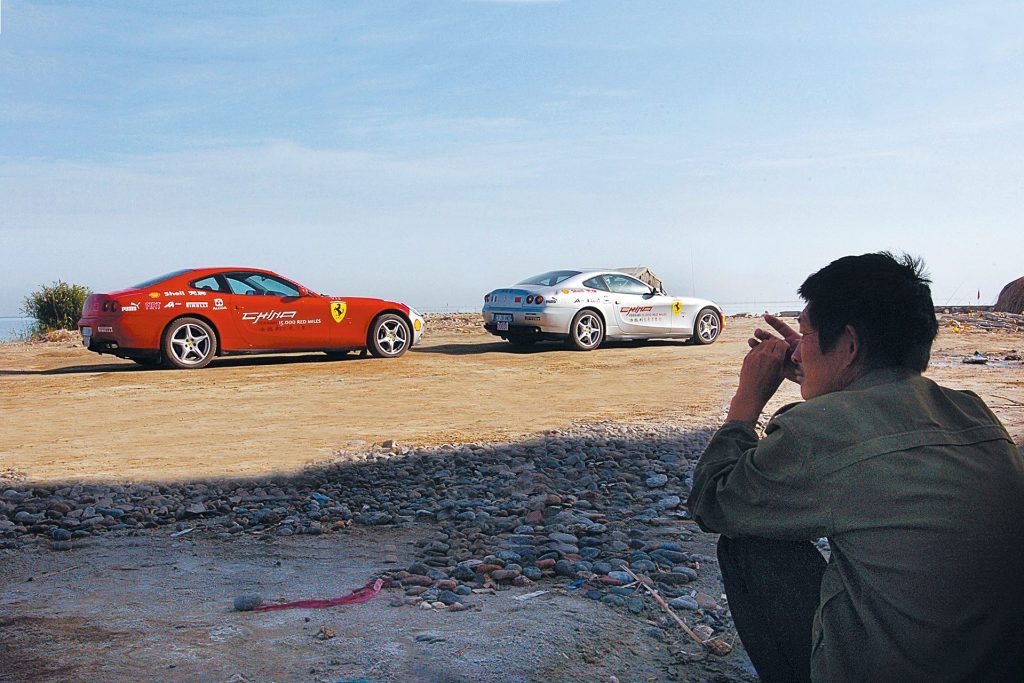

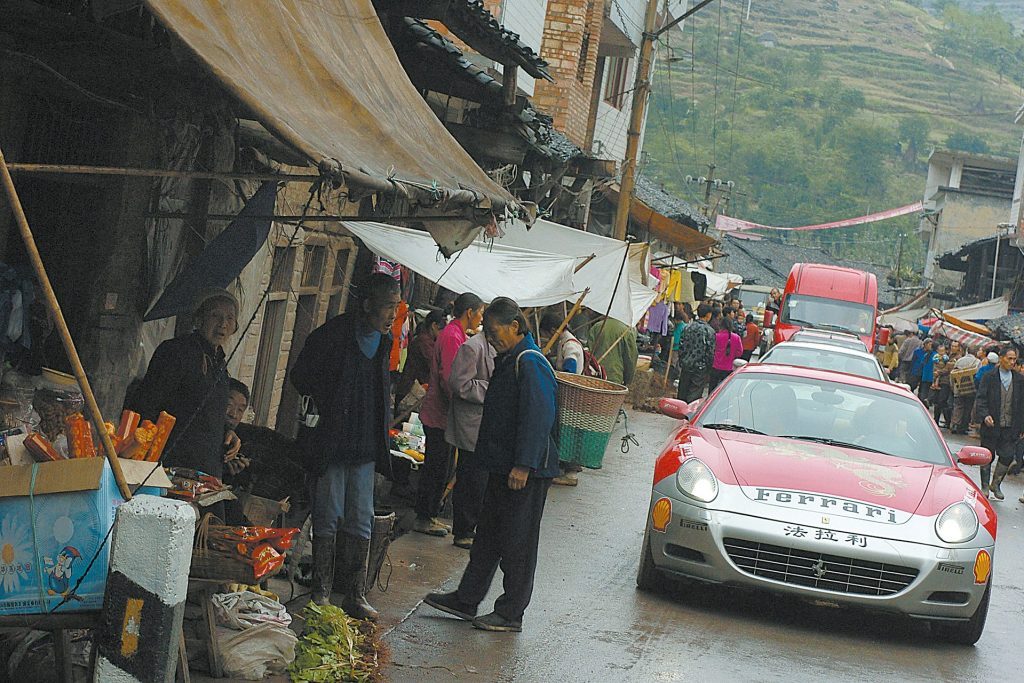

The 25,000-kilometre event was conceived by Ferrari’s PR team to showcase the brand to the rapidly growing wealthy sector in China, many of whom are still ignorant of the iconic status of the marque. With seven new dealerships opening in China, what better way to help establish a brand in such a vast country than to take two prestigious new 2+2 612 Scagliettis on a well publicised expedition criss-crossing China? Touted as an adventure, the tour was in fact more what I’d call an expedition; despite China’s vast population and its recent explosion in commerce and personal wealth, much of it is still remote. Particularly in the north, the mountainous terrain isolates vast regions, which are accessible only on foot and well beyond the reach of the motor car – or so you’d think. So if driving two high-powered, gas-guzzling, low-slung sports cars over such difficult topography at an average speed of less than 30km/h isn’t an expedition – or lunacy – then I don’t know what is. Add the hand of fate – even the best laid plans can go astray, and go astray they most certainly did on day two of our Chinese adventure – and it became an expedition of epic proportions.

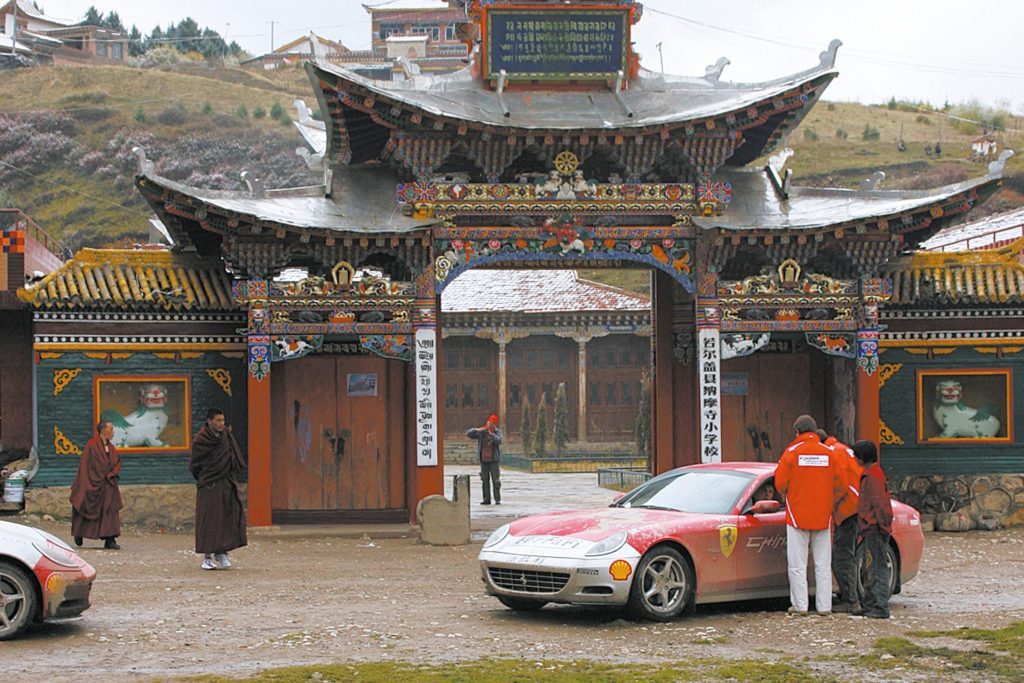

After an eye-opening (and bone-crunching) drive from the bustling city of Lanzhou, near the geographical centre of China, to the snow-covered highland township of Hezuo, it was decided to detour from the scheduled route to Ruoergai the following day because of unfinished bridge repairs en route. After much deliberation, our Chinese tour guide decided to head for Wenchuan, the planned third-day stopover. We pulled out of Hezuo on time at 8 a.m. and headed off for parts unknown, via the well-known Labrang Buddhist monastery on roads that quickly deteriorated into little more than rock-strewn dirt tracks. After four hours travel and some 90 kilometres, we stopped at crossroads, which doubled as a truck stop, Chinese-style, where our guide heard that yet another major bridge was down, a cause for great consternation. This would mean a significant backtrack, plus a huge loop of some 1000km, which would prove too time-consuming if our tight schedule was to be maintained.

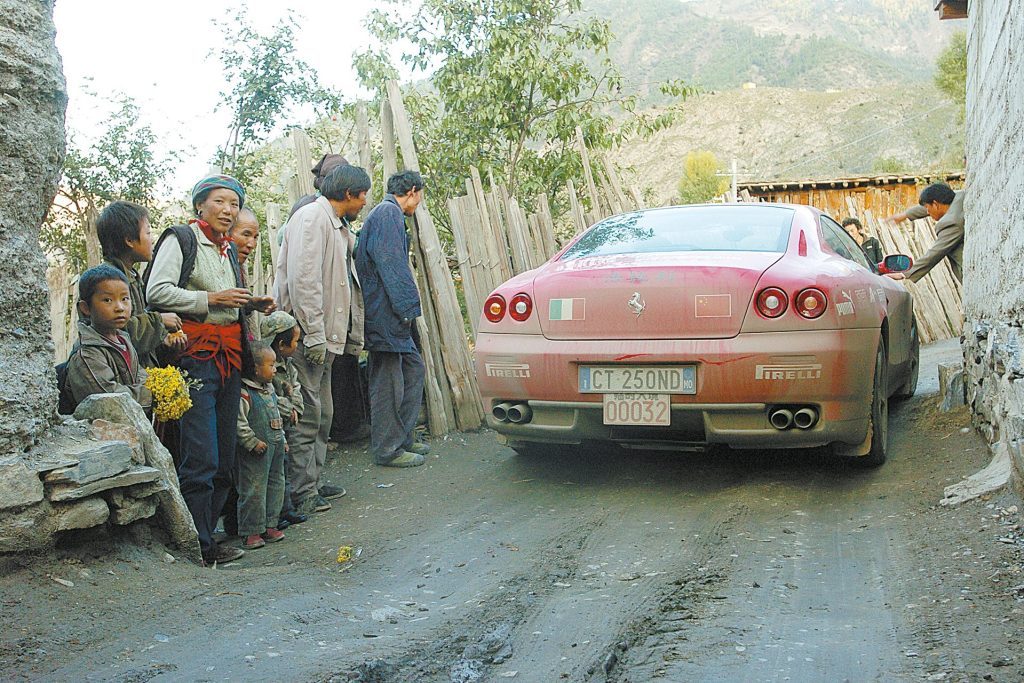

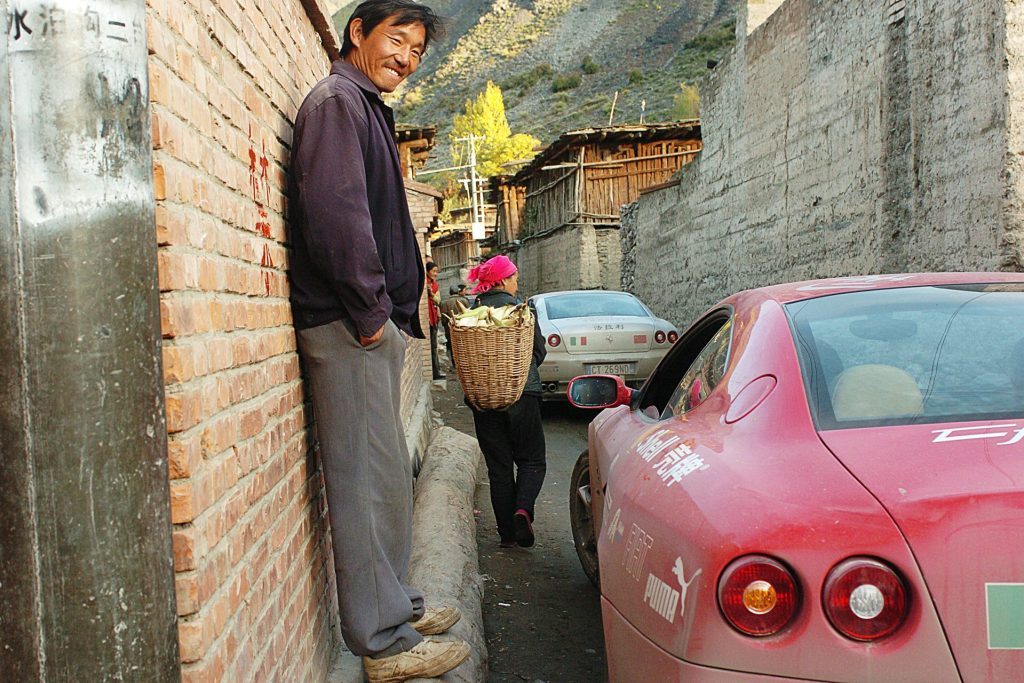

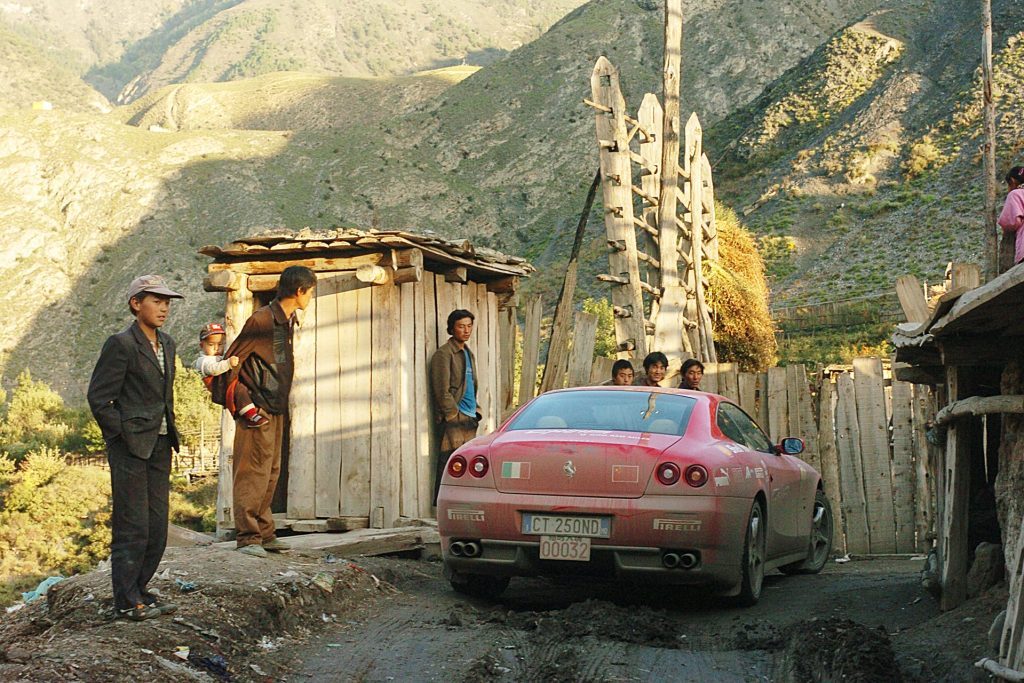

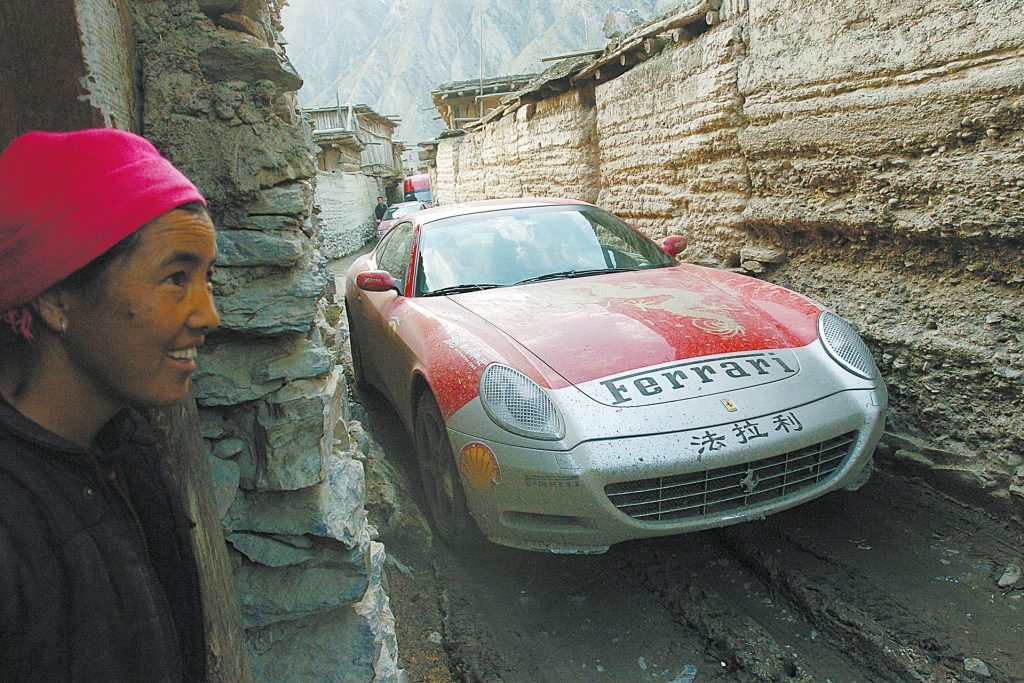

After much debate, mostly in excitable Italian, it was decided to check out the damage to the bridge first hand, so one of our two Iveco 10-seater support wagons was despatched down the torturous mud- and rock-strewn road to the nearest town 30km away. The relieved Chinese tour leader returned to say it might be possible to cross the river using a small village bridge further upstream and rejoin the main road again on the other side after a bit of backtracking. The risk we would have to take was, given they made it over the small bridge, that the generously proportioned Ferraris could squeeze down the narrow thoroughfares that separated the mud dwellings of the village. If we failed, we were to find consolation in the fact that we could overnight in the nearby township.

The local police chief, now sporting a new Ferrari jacket, personally escorted our convoy of seven vehicles to the alternative river crossing. It was less than confidence-inspiring. The bridge was squatting mere metres above a raging torrent that scythed its way through a ravine separating the road on one side and the village on the other. One of two locally built Fiat station wagons ventured gingerly down a steep, rocky track leading to the bridge and crossed up into the village to see if squeezing through the walkways of the village proper would be feasible. Twenty minutes later it returned, its occupants cautiously optimistic, but they informed us we would have to manhandle the rear of the Iveco vans around a particularly tight corner. The die cast, we cautiously picked our way down the track and, with some relief, crossed the bridge, then, inch by inch, manoeuvred along a precarious access path to the village high above, a near vertical drop beside us to the swollen waters below.

Both amazement and mirth greeted us as the villagers watched us painstakingly arrive, peering at our antics through the sun-bleached grey wooden staves that lined the entrance to their little community. We managed to negotiate the tight right-hand bend leading into the centre of the tiny village but had to make a three-point turn at a left-hander leading to its rear. The accompanying photos bear witness to the bare millimetres we had to spare between the mud-brick walls of the dwellings. But the damage was negligible, considering: a minor paint scratch on one of the Scaglettis.

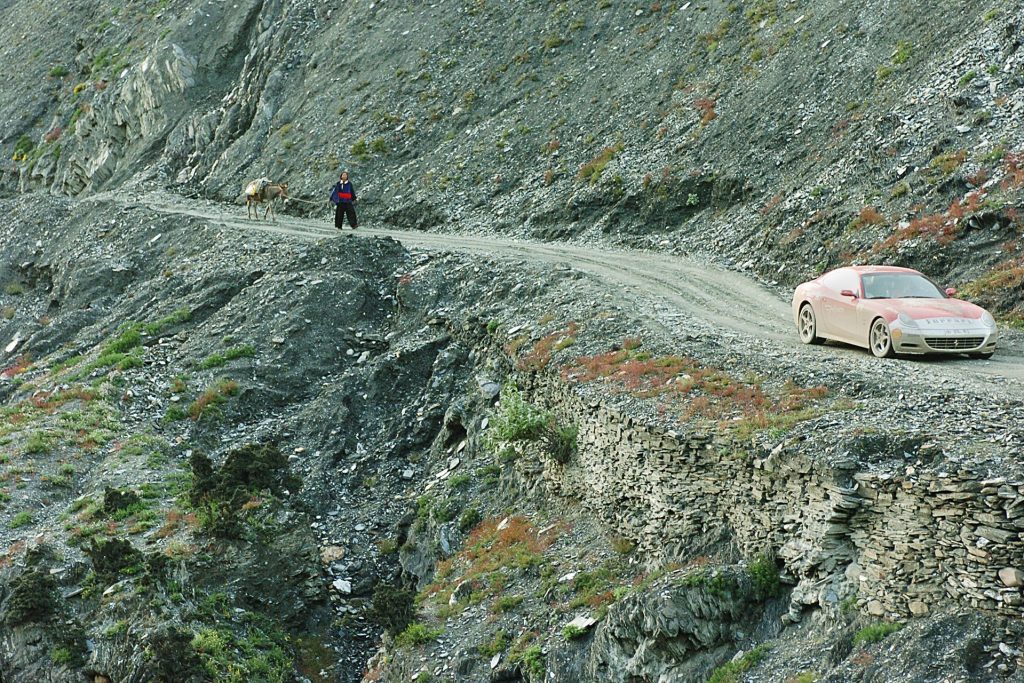

Any idea that the worse was over soon evaporated when we saw the track leading out of the village, which was cut across a steep face of shifting shale 200 metres above the swirling rapids far below. If you’ve ever negotiated Skipper’s Canyon above Queenstown and thought it pretty scary, well this was complete insanity. Our larger-than-life Italian tour leader, Luigino ‘Gigi’ Barb, was so concerned about the risk it posed to the big Iveco vans still threading their way through the village that he ordered them by two-way radio to turn around and go back to the township. Problem was, the Chinese support crew was literally stuck between a rock and a hard place: as it was impossible for them to turn around in the village, they’d have to back all the way down the road we’d already precariously travelled. So feigning a lack of understanding, they simply ignored Gigi’s broken English rantings and, much to our amazement, joined us half an hour later on the tar-sealed main road on the far side of the collapsed bridge that had thwarted us in the first place.

So eighteen hours after we had left Hezuo, we finally made it, not to Wenchuan but to Wienxian, a reasonably sized town located on the edge of the Tibetan plateau, boasting a three-star hotel to boot. I fell asleep, exhausted, on a bed as hard as a rock, its pillow made from dried beans. A scant five hours later after a fitful rest it was time to rise and hit the road once more. Fortunately, my room had the luxury of a weird but wonderful wall-mounted hot-water heater. Thank god for small mercies, as it was the first hot shower I’d had for three days, so the fact its rickety plastic base spewed water onto the bathroom floor and that it proceeded to rise at quite some rate because of a blocked drain worried me less than perhaps it should have. Reinvigorated and ready for breakfast, my appetite was quickly quelled by watching our Chinese support crew devouring the local fodder. Call me squeamish – looks like I’d have to survive a second day on dry biscuits and bottled water. Yep, this was an adventure all right!

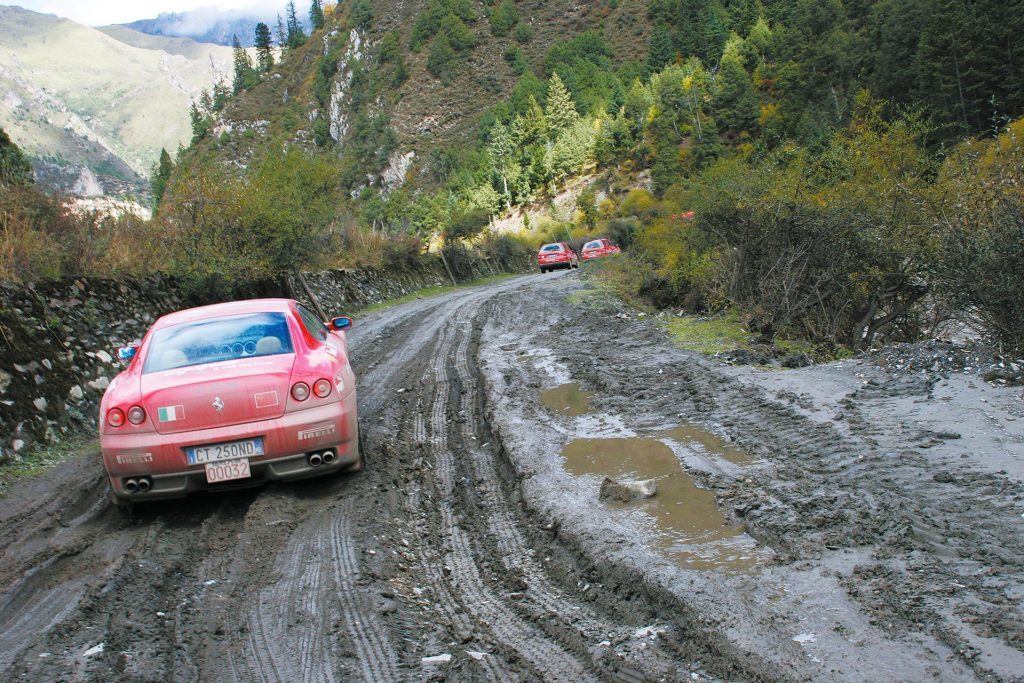

By day three, Gigi’s temper knew no bounds, and talk of “I’ll kill you, if you give me more shit roads today” were being shouted across the airwaves to our Chinese guide. Muphy’s law prevailed, naturally, and we were to encounter the worst road conditions imaginable, which necessitated creeping along mostly in first gear, constantly clutching in order to keep the wheels straddling the foot-deep wheel ruts. We soon learned that the trick was to put one wheel in the centre between the ruts and try to hold the offside wheels on the top of the ridge of mud and rocks forced up by the wheels of the omnipresent big trucks.

My luck eventually ran out in maintaining this precarious balancing technique and I embarrassingly bellied the beast. Rather than risk burning the clutch up trying to reverse back, I bailed out and invited Gigi to attempt to back it up and have another go – which he promptly did, much to my amazement. The electronic differential and traction control had to be experienced to be believed. Providing you crawled along in the mud and slush, the system refused to allow any wheel spin, Fotunately the rocky nature of the surface beneath the mud prevented us burying the cars in what was often a sea of mud. We never once had to tow either Ferrari out of the quagmire, and one time only did we have to resort to pushing the Scagiletti, much to my Australian colleague’s chagrin, when it corkscrewed itself across the wheel ruts.

Some eight hours later we finally hit the promised tollway that would take us into the prosperous city of Chengdu, 170km further on. Only then did we get the chance to wind the vehicles up, muddy debris flying from the two Ferraris as we burst through 200km/h, only to be forced by vibration from the mud-caked wheel rims to run at a more sedate pace along the sealed stretch of twin-lane ‘motorway’.

Our next challenge came as the sun fell below the horizon; the beams of our headlights severely restricted by chromed stone protectors, resulting in scant illumination of the road ahead. In the dusk, great potholes would suddenly loom out of the gloom, and they proved every bit as dangerous as the previous 1000km of mud and slush.

Fact is, the many Toyota Landcruisers we encountered were the uncrowned kings of this terrain; their ilk could sail serenely over roads that reduced our Ferraris to a crawl. Little wonder that their high-riding occupants stared down at us inching along, their faces a picture of disbelief and utter amazement.

All in all, it was an amazing experience. The ability of a near-supercar to survive 22,000km of snow, desert, sand, mud and rocks is a testament to the build quality and strength of a modern Ferrari. The Scagletti was raised a mere 15mm to fit a protective steel underbody tray, and each car carried an extra 45-litre alloy tank of fuel in the boot, which meant the rear passenger space was filled with soft luggage bags. The engine ECU coped brilliantly with all manner of low-quality fuel, from 89 to 91 octane.

Impressive? Yes. Foolhardy? Very. Do it again? No. Not that any owner of any supercar would wittingly set out to tackle such a landscape. So it’s more a moot than comforting point to know that, carefully driven and with the assistance of the electronic differential and traction control, you can traverse slippery surfaces as extreme as those that China threw at our Scaglettis.

This article first appeared in the December 2005 issue of NZ Autocar Magazine.