1982 Lancia 037 Stradale & 1986 Delta S4 Stradale

Words/Photos: Richard Opie

Group B conjures up images of flame-spitting monsters, chaotic soundtracks and hordes of rallying faithful risking it all for a glimpse of the pandemonium. Lancia was at the forefront of the battle with its 037 and Delta S4 weaponry.

If ever there was an adjective to wholly summarise arguably the wildest years of world rally competition, it would be superlative. We’re speaking, of course, of the Group B era. Almost mythical in status, it spanned only five seasons from 1982 until its demise at the end of 1986, but it’s a period that’s destined to hold reverence among fans forever. Not only was it responsible for a collection of machinery pushing (and exceeding) the limits of outright performance with seemingly physics-defying pace, but the involvement beyond the drivers and manufacturers themselves was something to behold. Spectators clamoured en masse to witness their heroes dancing from peak to peak of Finland’s swooping topography or skating across the ice of Sweden’s winter wonderland. And Kiwis got a share of the action, with the rifle-crack bangs echoing across Aotearoa’s valleys as the world’s best chucked gravel over number-eight wire fences with deft application of the right foot.

All of this was down to the Group B regulations. These essentially removed many of the cost implications for manufacturers to homologate rally weaponry that only a year prior had seemed the stuff of dreams. Manufacturers only needed to produce 200 examples of their chosen machine – far fewer than the 5000 required for Group A – and although the original Audi Quattro was homologated under the previous Group 4 rules, it’s evolution as a Group B car was, without doubt, responsible for the arms race that was to follow.

Lancia wanted a piece of the action. By this stage, the marque was pretty much synonymous with rallying homologation specials and, in particular, engineering winners. The Stratos, famously the first car designed specifically for rallying, won three consecutive championships from 1974 to ‘76. Not only that, but it did it in characteristically Italian style, with a Bertone-designed ‘wedge’ bodyshell enveloping a Ferrari-derived 2.4 V6. It was an exercise in dominance, and despite a brief sabbatical, when Group B dawned Lancia decided it wanted more of the limelight.

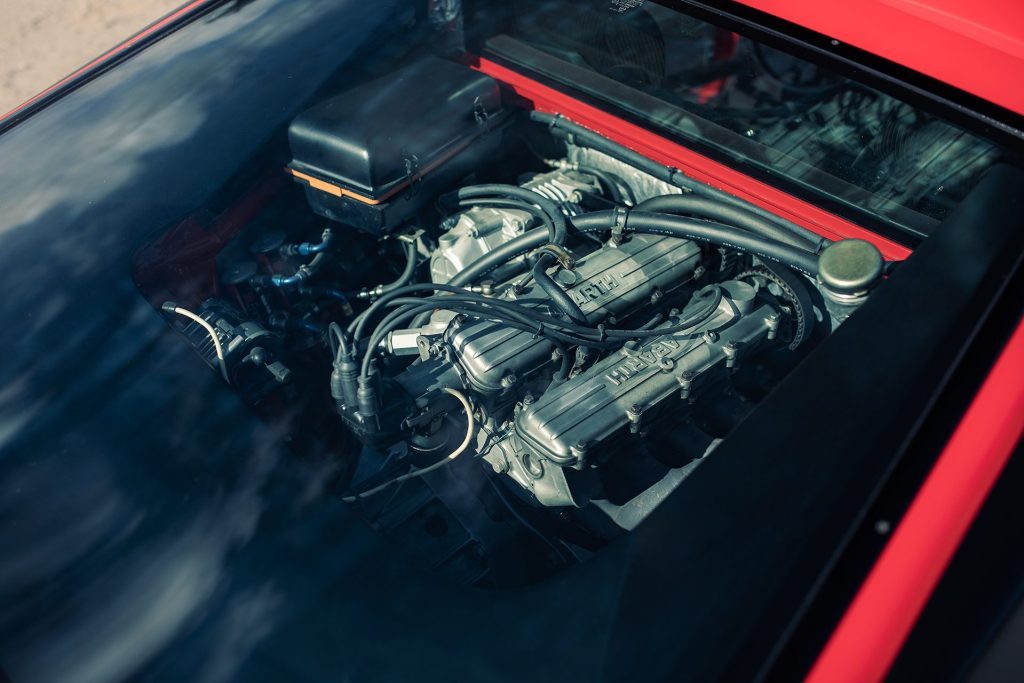

Being part of the Fiat group, the development of Lancia’s initial Group B challenger would be handled by Abarth. When the FIA’s rules were announced in 1981, the Group B project was assigned the number ‘SE037,’ a moniker that in part would remain with the final product, bearing the traditional Lancia badge alongside the simple ‘037’ model name.

Rather than starting with a totally blank sheet, Lancia instead focused their efforts around an existing road car, and in the 037’s case, this was the Lancia Beta Montecarlo.

The Beta Montecarlo was no world-beater, however, despite typically-Italian sporting aesthetics. Behind the drivers head was a raucous 2.0 Lampredi twin-cam, pumping out at best around 120hp, with MacPherson strut suspension and little in the way of serious performance accoutrements.

And so Abarth’s team of engineers, headed up by Sergio Limone who mastered the Fiat 131 Group 4 rally car, took to the Montecarlo. Only the middle was retained, with Limone and his team effectively lopping off the front and rear sections and grafting newly-fabricated tubular ends onto the Montecarlo ‘capsule’. This was then all tied together with integrated roll protection, visible even when peering into the interior of the homologated ‘Stradale’ road car, of which 217 examples were eventually screwed together at Abarth and let loose.

Mac-strut suspension was hardly likely to cut it, so a double A-arm arrangement was bolted up, with an intriguing double-shock layout in the rear, coping with the bulk of the 037’s mid-mounted engine and transaxle. The shapely composite body was designed by Pininfarina, itself capable of low-drag, high-downforce performance – even more so when the later ‘Evolution’ variants hit the stages.

Forced induction was a must for Group B and Lancia chose supercharging for the 037, with a Roots-type blower slung off the 2.0 Lampredi twin-cam, which itself was mounted longitudinally rather than the transverse arrangement of the Montecarlo. With a handy 205hp, the Stradale’s kerb weight of a shade over 1000kg made it a formidable road car but in amped-up Group B competition form, the 037 would peak at 325hp and 960kg in 1984-85 2.1-litre, 16-valve ‘Evolution’ guise.

However, the 037’s rallying life wasn’t a strictly beer and lamingtons affair. Although well intentioned, the lithe, pretty little rallying machine’s Achilles heel was the simple fact that only two of its wheels were driven. The Quattro had become the dominant force, and while the 037 snatched five victories, and the last ever constructors’ championship for a two-wheel drive car in the 1983 season, 1984 saw the 037 yield only one victory in Corsica – on asphalt.

The following season was even worse, with the new Peugeot 205 T16 elevating the game further, and Lancias misery compounded by the tragic death of Attilio Bettega in Corsica, causing Lancia’s withdrawal from the event. A brighter note however was the clinching of its third European championship in a row, but by now Lancia was deep into the development of its four-wheel drive beast.

To succeed the 037 and compete with the dominant forces of world rallying, Lancia was going to need something special up their sleeve. And lordy, did they come up with a contraption.

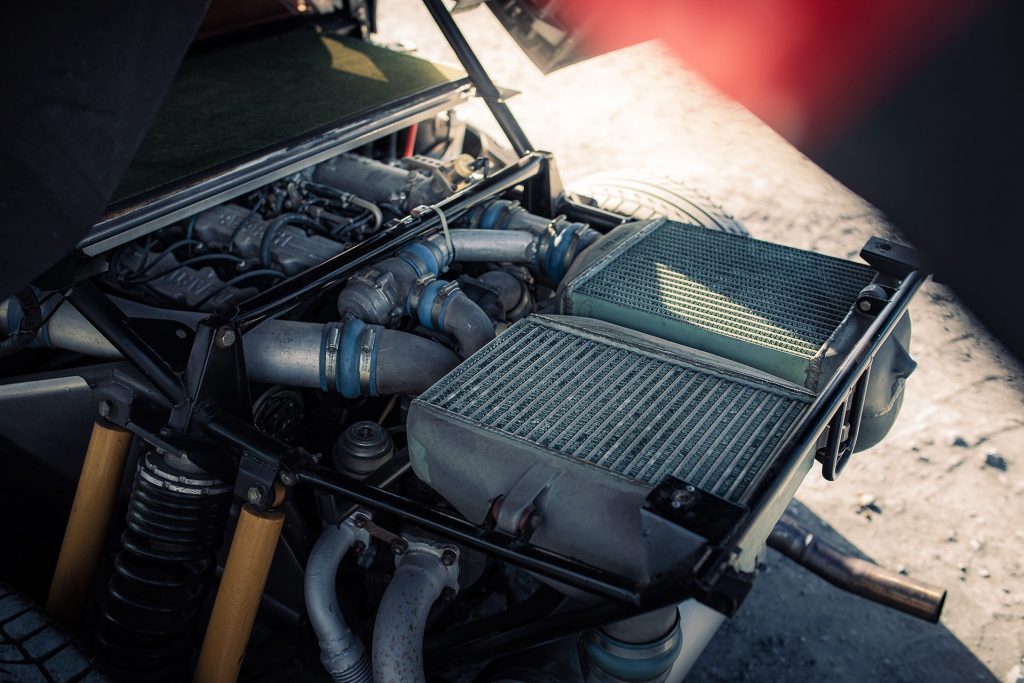

Logically, the project was given the moniker ‘SE038,’ and again Limone was involved, despite having zero prior experience with four-wheel drive. At its core, the SE038 project drew on some familiar territory. The car would again be built around tubular front and rear subframes with double-A arm suspension front and rear. While the project would eventually be named the Delta S4, and bear a passing resemblance to the Delta road car, there was absolutely nothing production based about Lancia’s new weapon.

The S4 would feature a complete tubular spaceframe, with its somewhat ungainly looking bodywork constructed from a carbon-fibre and kevlar composite. Even on the road-going Stradale version, the composite’s weave is visible through a thin coat of paint.

Aesthetically, the S4 couldn’t be considered beautiful, unless an onlooker finds beauty in absolute function prioritised over form. The bodywork bristles with vents and blisters, with the primary goal being ultimate performance. Abarth utilised extensive wind-tunnel assistance in finalising the appearance of the S4 which, for the day, was unprecedented in rallying.

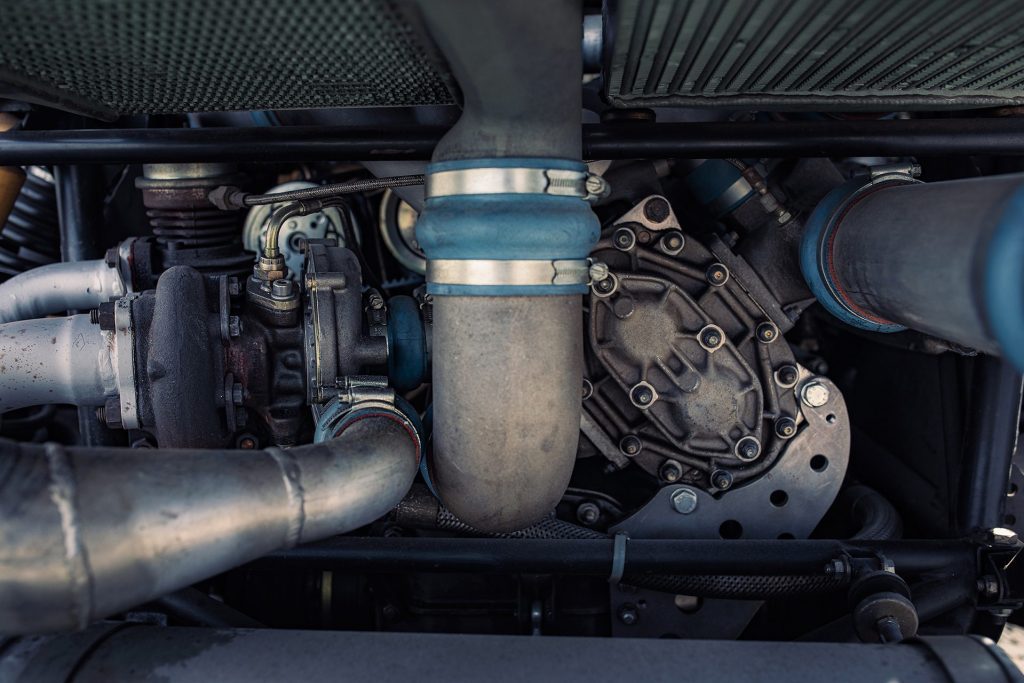

The mid-engined, four-wheel drive layout wasn’t, however, with the aforementioned Peugeot 105 T16 resetting the benchmark for Group B. Abarth again chose to lay out the Lampredi twin-cam in a longitudinal arrangement. Contrary to the engine used in the 037, the Delta S4 instead used a bespoke variant of the design, inspired by F1 tech.

Displacing just 1759cc, the new engine was a considered choice. Thanks to the FIA’s 1.4-times multiplier for forced induction engines, the smaller mill would ensure the Delta S4 could run at a lighter weight, needing to meet a minimum of just 890kg. Abarth and Lancia would go on to not only supercharge the twin-cam 16-valve engine, but would also add a turbocharger. The theory behind ‘twin charging’ as the concept became known, was the supercharger would provide critical low-end oomph, while the turbocharger would take over the reins at a pre-determined rev point. It relied on a complex valve system on the intake side to shut off the supercharger and vent any unneeded boost as the engine screamed to the top of its 10,000rpm rev range.

Even the Stradale road car is an angry little box. At idle, the twin-charged lump whirs away with a mechanical cacophony that amplifies exponentially with each prod of the loud pedal. While the Stradale version would develop a comparatively modest 250hp, the race version proved a potent competitor. Epitomised by the howl of its supercharger and violent crackles ensured by the turbocharger and wastegate, the full-fat Delta S4 would produce a shade under 500hp, although in stress testing Abarth engineers claimed over 1000hp out of the unit when fed five bar of boost.

Homologated in time for the final round of the 1985 championship, the Delta S4 hit the stages in Britain for the RAC Rally and promptly won. Lancia’s young prodigy, Henri Toivonen, claimed the top step of the podium, leading home Markku Alen for a Lancia 1-2 sweep.

For 1986, things kicked off at the Monte Carlo rally, and again, Toivonen and the S4 proved unbeatable. The Delta looked to be a genuine contender, breaking over a year of dominance by their Peugeot adversaries.

But while the S4 was blisteringly quick, it was fragile and the lightweight tube-frame required frequent attention following each rally. The composite bodywork (including the floor) was prone to cracking, and the highly strung 1.8-litre with forward-facing transmission meant the cabin was a hot, inhospitable place for a driver.

Ultimately, it was the pursuit of lightness that would tragically blight the S4’s career, and contribute to the demise of Group B on the whole. For Corsica, the Lancia team had put the cars on a diet, aiming to maximise performance on what had become the defacto home for Lancia’s rally contenders.

Toivonen and co-driver Sergio Cresto flipped over a stone wall, rolled down a rocky slope into the trees and their S4 ignited. Both drivers would not survive the explosive impact, believed to be due to tree branches puncturing the already-infamous underseat fuel tanks of the Delta S4. As part of the weight saving regime, Lancia had removed the skid plates protecting these fuel tanks, leaving them exposed to damage, with the extreme weight-saving philosophy ultimately costing the life of one of rallying’s brightest stars.

The incident proved one of the final nails in Group B’s coffin, with spectator and driver deaths and injuries peppering the final two seasons. The Group B spectacle had become unmanageable, but nonetheless the championship pressed on for the remainder of the 1986 season and the S4 continued a successful run. Podiums at the Acropolis and in New Zealand would follow, and another 1-2 in Argentina. Third in Finland, then a 1-2-3 sweep in San Remo at the expense of Peugeot being disqualified for illegal skirts, a controversy that would result in all points being cancelled from the event.

The S4 would perform well again at the RAC, with Alen taking second, before a win on the final round of the 1986 calendar on the Olympus rally. Markku Alen would be provisionally crowned 1986 champion, a title wrested from his grasp after the San Remo points debacle, narrowly missing out to Juha Kankkunen aboard the 205 T16. Lancia would also go on to miss out on the manufacturer’s title, although many surmise that if it wasn’t for the loss of Toivonen, the Finnish ace would have likely gone on to be driver’s champ, and Lancia king of the constructors.

The sun would set on the 1986 season, taking with it the heady heights of Group B competition and the Delta S4’s promising career. With Group A on the horizon, it merely heralded the dawn of Lancia’s most dominant period yet with the Delta Integrale, but the spectacle of Group B will remain forever etched in the psyche of rallying faithful and casuals alike, with the legend of the S4.

That a couple of Stradale examples of Lancia’s group B superstars even reached Kiwi shores seems almost unthinkable, given the relative rarity of these vehicles. Yet, thanks to a prominent Auckland Lancia collector and enthusiast, we’re lucky enough to see these examples out enjoying the Kiwi sunshine.

It’s the culmination of a Lancia habit beginning during university years, with the acquisition of a 1971 Fulvia Series 2 kick-starting the addiction. “It started in 1986, with a burnt-out insurance write-off,” our Lancia enthusiast explains. “I took it home and became absolutely passionate about it, to the point it cost me my BSc exam results!”

The Fulvia’s now completed over 120,000km of driving and is nearing the end of its third rebuild, as it’s “been thrashed, and enjoyed!”

“Now I’d always loved rallying, and I’d heard of Lancia because of rallying. The Lancia’s were my favourite, and when they brought the 037 to New Zealand I thought it was just such a beautiful thing, like, how can something so utilitarian look so beautiful?”

“Then along came the S4 and it was like listening to a chainsaw on steroids in the forest. These things were so fast you wondered how the drivers were hanging on!”

Nonetheless it planted the seed, and with a growing collection of Lancias (now featuring some 30 roadworthy examples), not to mention a financial position to really start looking for these special examples, the hunt began.

“I found the S4 in Japan in 2015, but didn’t have the means to buy it and got outbid by a guy in America,” he explains. The car had only 2000km on the clock at that stage and needed a thorough recommission, which the USA owner duly did. The extent to which the car had been brought up to spec wasn’t clear until it came up for sale again as Covid began to take hold.

“I asked for receipts for the work done, and it came with all of these hotel bills and flights,” laughs our intrepid collector. As it transpired, the owner had enlisted one of the Baldi brothers – the tuning forces of 1980s Abarth – to fly across and recommission the Delta. Nothing like the best to revitalise one of the most iconic.

“I ended up buying it and the trick then was getting it out of New York with all the Covid mess, so I basically enlisted this guy who used to be a Serbian commando. He specialises in getting cars out of weird locations, ready for export!”

“He picked it up on a 20-car transporter – it was all he could find – and drove it across the States to LA with just the one car sitting on the top deck of this massive transporter, out of the way of rocks and road debris!”

Shipped across in a container with a DeLorean and a Pantera, the Lancia arrived on Kiwi shores, ready to be complied and taken for a drive. “I was a bit nervous, there’s so much going on under the surface of this car, and it’s so angry you’re just waiting for an explosion at any time!”

The driving experience is described as “fearsome,” especially compared with the 037. “The supercharger gets you off the mark then the turbo kicks in and it’s like a jet fighter.

“It just assumes this whole new identity, this vibration. It feels like it’ll race around any corner, you pull on the wheel and it just goes.”

“The 037, then, is a bit more of a sedate animal. Where the S4 demands presence simply by virtue of its pure aggression, the lithe, delicate nature of the 037 is underlined by a comparatively gentle whir from its engine on idle. It wakes up with some revs, assuming the traditional Lampredi twin-cam snarl, augmented by the whizzing Volumex blower.

“They’re easier to find than an S4, but hard to find in decent nick,” the owner explains. “They’ve all been rallied or gymkhana’d and Lancia spent a bit less money on these compared to the S4 so they do deteriorate.”

Found in Japan, the 037 was claimed to have had a recent refresh, with the engine sent to Italy for a rebuild. On arrival, a few rust issues required rectification but in the owner’s eyes “it’s still one of the most beautiful Lancias, especially when you compare it to the brutalist S4.”

“When you drive it, it just wants to go places, it just wants to dance,” he mentions of the driving experience. The 037’s poise is evident in nostalgic rallying footage too, tip-toeing atop its chosen surface, darting from corner to corner in nimble fashion.

With two distinctly different road-going Group B experiences on hand (not to mention a Stratos and Delta Integrale) it’s astounding to have such iconic examples of one of motorsports most revered periods out on Kiwi roads.

It’s one thing to read about these machines but to experience the sight, smell and aural sensation in the metal, it simply cannot be understated. Group B may be gone but it will never be forgotten.