1981 Mazda RX-7 Group C Tribute

Stephen Armstrong’s Group C RX-7 tribute harks back to an era where politics spoke louder than it’s straight through pipe – a tale of prevailing and succeeding.

Looking back through the annals of automotive history, be it manufacturer showroom offerings or circuit-honed competition thoroughbreds, it’s tricky to bear fruit more controversial than the trials and tribulations associated with the rotary powerplant.

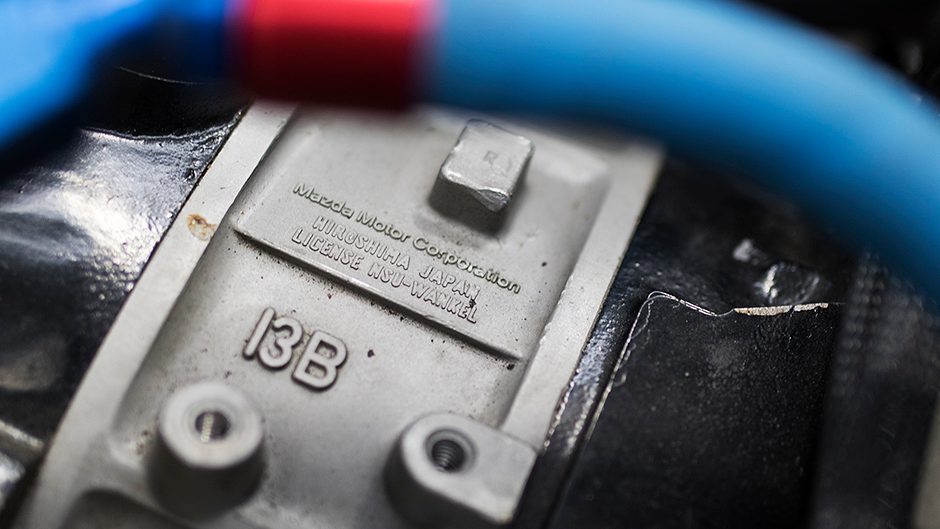

Conceived by Germany but refined by Japan, Felix Wankel’s creation did away with established thinking and challenged the reciprocating convention. Traditional cylinders gave way to epitrochoid-shaped chambers while pistons relented in favour of roughly-triangular rotors, resulting in an assembly promising silky smooth running with the benefit of substantial power from a comparatively small swept volume, not to mention the compact dimensions.

Of course as history has proven, the rotary hasn’t been without its problems – a reputation for somewhat questionable reliability, longevity below that of its reciprocating cousins and of course the innate ability to churn through copious quantities of refined crude oil. The niche pathway the rotary engine carved merely fuelled the rivalry between up-and-down versus round-and-round.

As far as Australasia is concerned, the fever-pitched controversy associated with Mazda Australia, Allan Moffat and the RX-7 Group C programme for the Australian Touring Car Championship between 1981 to 1984 best exemplifies the polarising nature of the rotary engine in competition. As an improved production class, the Group C era was itself marred with off-track battles disputing legality. Mazda Australia’s application to CAMS to homologate their 12A-powered RX-7 for the over three-litre category raised eyebrows – and the ire – of more than a handful of would-be competitors, regardless of the fact that the chassis had already received the FIA tick to compete in Group 1 touring car races in Europe.

At the crux of the controversy was Mazda’s desire to campaign their 12A rotary engine with a modification known as peripheral porting. Simply put, the inlet ports were shifted from their original location on the end plates to the sides – the periphery – of the rotor housings themselves. This allowed the engine superior breathing over the stock arrangement, likened perhaps to installing a more aggressive cam profile, extensively porting the cylinder heads and popping a set of larger valves into a V8 – which of course was very much the norm, by the Ford and Holden teams that were very likely to be Mazda’s core competition.

In December of 1979 the approval was granted by Australia’s motorsport governing body, only to be revoked less than two weeks later following competitor protestations. Moffat and Mazda persisted, provoking a five-month period of deliberation which finally resulted in a positive decision allowing the RX-7 to race – only to be disallowed again, mere days later. Many mortals would have walked but Moffat stood firm, pleaded the RX-7’s case and finally a year later, CAMS gave definite approval that the song of the rotary engine would soon be heard among the pounding pistons of the Australian Touring Car Championship.

Beginning with a carburetted 12A pumping out around 270bhp at an ear-splitting 8500rpm, the Moffat cars hit the track with the now iconic Peter Stuyvesant livery wrapped around the RX-7’s lithe silhouette, muscled up with the addition of Group C-specific flares and aerodynamic aids. Throughout their competition career, Moffat and the SA22C chassis RX-7 ran competitively, notching up a considerable tally of race wins and the 1983 championship despite a swathe of angry criticism, although the ultimate – a Bathurst victory – eluded the team.

It was around this time that the rotary spark was ignited for Stephen Armstrong, owner and builder of this immaculate and accurate tribute to the Allan Moffat RX-7. The purchase of an RX-3 coupe by a work colleague sometime in 1980 sowed the seeds – “It looked like a mini Mustang, was faster than anything I’d driven and I knew I had to have one.” Acquisition of his own RX-3 led to immediate involvement in the Mazda Rotary Enthusiasts Club (MREC) and a swift introduction to a variety of motorsport disciplines.

With such immersion in the culture of all things rotary, Armstrong has also been privileged to indulge in his passion alongside a few of the greats of the Kiwi rotary tuning scene. Among them, Bill Shiells, founder of Rotorsport and revered highly enough that even Mazda themselves enlisted his know-how on rotary tuning, and Pete Smith, handy with building rapid rotary street engines. Armstrong acknowledges a “lifelong friendship” with Smith who no doubt provided expertise and inspiration for a swag of Mazda rotary weapons that have littered the former’s automotive past.

These include an RX-2 Capella coupe, nicknamed ‘Casper’, that went on to win a GT championship in the hands of Alec Bell, and a ’75 RX-3 Savanna Coupe which packed the first 13B motor in the country. Close association with both influential members of the rotary scene, as well as MREC, led to Armstrong’s involvement in the founding committee of the Pro 7 championship for which he wrote the technical regulations. The infatuation with Mazda’s unconventional approach to propulsion is clear, and some years down the track there was only going to be one variant of engine powering Armstrong’s choice of race car, manifested here in the form of a 1982 SA22C Mazda RX-7.

While he vowed to own a Moffat car, when a genuine #43 RX-7 came up for sale in Australia, the $250,000 price tag didn’t quite align with his and wife Jalaine’s racecar budget. The decision was instead made to piece together a tribute build of their own, as close as practicable to the real deal.

Stephen’s RX-7 commenced life with appropriately humble origins. Bought as a basic road-cum-club car, he describes the RX-7 as being a “simple straight car, a good starting point with a few good bits already.” The call was made to give the car a quick refresh but with “one thing leading to another,” the project burgeoned into a full, period-correct Group C replica build.

Armstrong became adamant that the build of the RX-7 had to be kept in line with the methodology of the Group C cars of the period. As per the Moffat cars, this dictated the retention of the Series 3 RX-7 differential equipped with an adjustable Watts linkage. While it was the strongest of the first-generation RX-7 era, the diff was still no match for the 10-inch wide slicks the car runs on track and Armstrong recounted myriad axles and diff components that have fallen victim to the levels of grip offered by modern tyre technology.

All four corners of the RX-7 feature adjustable Koni race shocks, controlling carefully chosen King race coils, again a simple arrangement befitting of an era where cornering grip was seemingly improved by throwing more and more inches of rubber at the road. In the case of Armstrong’s car, locally produced three-piece Arrow mesh wheels – close facsimiles of the genuine BBS items used by the Australian cars – measuring 17 x 9 inch front and 17 x 10 inch rear employ 245 section front and 265 section rear slicks in order to keep the car shiny side up. Braking is kept simple and in the family, OEM issue FD3S RX-7 four-pot calipers and rotors provide the requisite friction at the front, while the rear again features FD3S items.

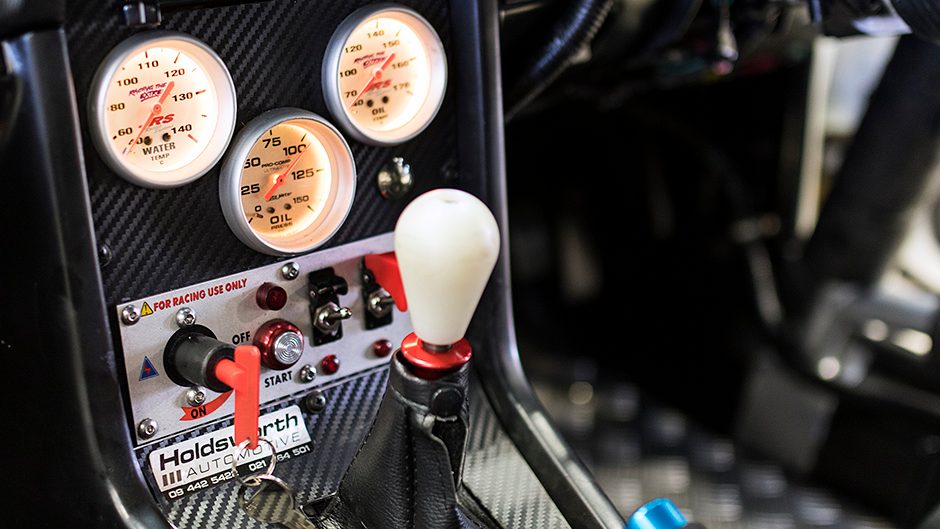

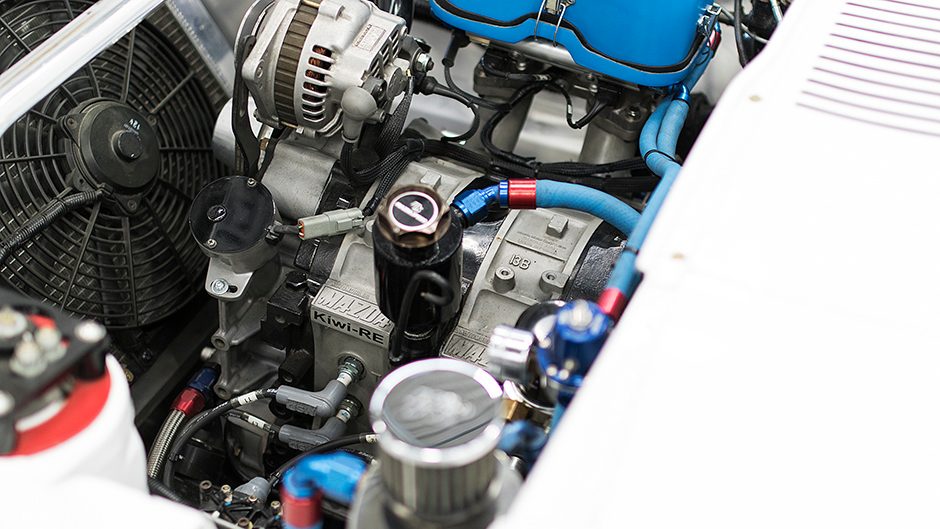

It’s beneath the bonnet where things get properly serious. As an improved production formula, the Group C rules allowed for a number of modifications to the engines in order to extract as much power as possible, hence the misty-eyed nostalgia of ‘the big bangers’ closely associated with the era. In 1984 the Moffat cars received dispensation to run the larger 13B engine. Stephen’s car packs a Kiwi RE-built 13B, put together by long-time rotary expert and Armstrong associate Alec Bell. It is complete with controversial peripheral porting to MFR specification as well as a lightened, balanced and clearanced rotating assembly so typical of a race-built rotary. High compression rotors aid in combusting the fuel and air mixture drawn in through an EFI Hardware 51mm IDA type throttle body, before expelling the spent gases via a free-flowing stainless steel exhaust. Peering into the engine bay the obvious feature is the large blue cold air inlet plenum, again a facsimile of the period factory-produced item. With 320bhp at the rear slicks and a powerband between 7000 and 9000rpm the car is no slouch. Inside the cabin it’s all business, with retention of the original dashboard juxtaposed with a stripped interior, single race seat, comprehensive roll protection and the sealed off fuel system located in the rear load area of the RX-7.

No proper tribute to a period is complete without the right livery, and the Peter Stuyvesant warpaint worn by Stephen’s RX-7 is absolutely on point. Hundreds of detailed photographs provided the blueprint to get it right, a factor many replica liveries miss when it comes to spacing, line thicknesses or proportion, but the RX-7 gets it right, showcasing a time when tobacco sponsorship ran rampant and muscle was defined by the size of your wheel arch flares – in this instance an exact replica of the Moffat aero.

One of the issues encountered with building a car to a period specification is that the driving characteristics don’t quite measure up to modern standards. As the RX-7 is still running an OEM steering box as per 1984, and with large sticky tyres, Armstrong admits the driving experience “is hard work.” The car debuted at the 2013 Leadfoot Festival, but the quest now is for more seat time. Both Armstrong and the RX-7 will return to Millen’s Mile for 2017, while also competing in the Rotary Racing Enthusiasts rounds this coming summer, with the goal also to run with the ever-growing Historic Touring Car grids. But the question has to be asked, will the return of an RX-7 to a classic touring car grid awaken the same controversy among competitors and rulemakers alike, as it did 35 years prior?