Packard Motor Museum tour

Words Paul Owen | Photos Tom Gasnier

How one man’s attempts to chronicle the technological march of the 20th century would lead to one of the world’s largest collections of Packards being located at Maungatapere.

Anawhata Trust Museum’s Fenton Craw can’t confirm whether the group has gathered together the largest collection of Packard cars in the world, housed in the former dairy company buildings at Maungatapere, west of Whangarei. But at 61 examples, it’s pretty close to being the biggest muster of cars bearing the brand’s logo.

“There is a collection of similar size in Warren, Ohio, and we’ve asked them to count their cars. “They haven’t got back to us with the number yet, but if they have more, then I’m prepared to buy a few more. “Until then, I can only confirm that this is the largest collection of Packards in Maungatapere,” he grins.

Research suggests that the Anawhata Trust has amassed a greater collection of Packards than the 50 cars on display at the award-winning American Packard Museum. That’s located in a restored art deco-style former Packard dealership in Dayton, Ohio. The other rival for the ‘largest collection of Packards’ title is also in Ohio, for Warren was the town where James and William Packard, and their partner, George Weiss, built the first 400 cars to wear the name from 1899 to 1902.

That start-up was similar in its inspiration to Lamborghini’s. James Packard, a pernickety engineer, was offended by the crudeness of the Winton cars that his mate, Weiss, had invested in, and complained to Alexander Winton while making suggestions on how to improve them. When Winton snubbed him, Packard then persuaded Weiss to invest in better cars – those of his own design.

Such was the reliability of the early single-cylinder Packards that they soon attracted the attention of a group of New York and Ohio Automobile Company investors led by Henry Joy and Russell Alger. The huge dollop of cash bought by these members of old Detroit families transformed the NY&O company into the Packard Motor Car Company, which moved to Detroit. The extra capital also allowed new President, James Packard, to realize his dreams and make luxury cars.

Where other fledgling Detroit car makers like Black, Ford, and Oldsmobile were making ware costing $400-$650 while using the more efficient assembly line manufacturing methods patented by Robert Oldsmobile, Packard aimed higher, producing cars with $2600 entry prices.

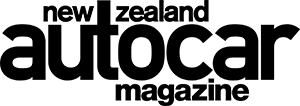

Packard’s innovations, like the world’s first steering wheel and the first production V12 automobile engine, soon attracted the rich and famous to the brand. Notable Packard customers in the lead up to World War One included the Russian and Japanese imperial families, and many stars of then-silent movies.

Along with Pierce-Arrow and Peerless, Packard became one of ‘the three Ps’ – brands starting with that letter – that were taking the luxury car sales fight to Cadillac. Packard got a big lift to its prestige when it hired former Hudson engineer, Jesse G. Vincent, a founding member of the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) in 1912.

Immortalized as “America’s Master Motor Builder”, Vincent would leave his mark on every engine produced by Packard until his retirement in 1946. He developed the first production V12 car engine in 1915 even before the format was known by that name, calling it the ‘twin-six’ instead. The 6.9-litre motor would serve Packard well, and Vincent’s expertise would be called upon by the US War Department in 1917, to lead the development of the famous Liberty V12 aero engine.

The most powerful engine of its type, the Liberty arrived too late to influence the war, but many of the 30,000 Liberty engines made by Packard became the boat racing motors of choice during the 1920s, ushering the ‘ask the man who owns one’ brand towards a mid-war peak in both fame and favour.

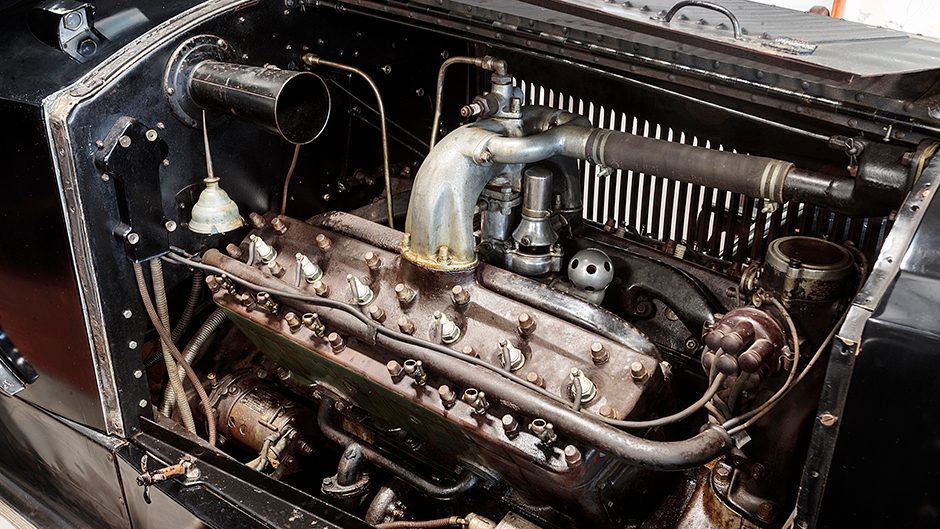

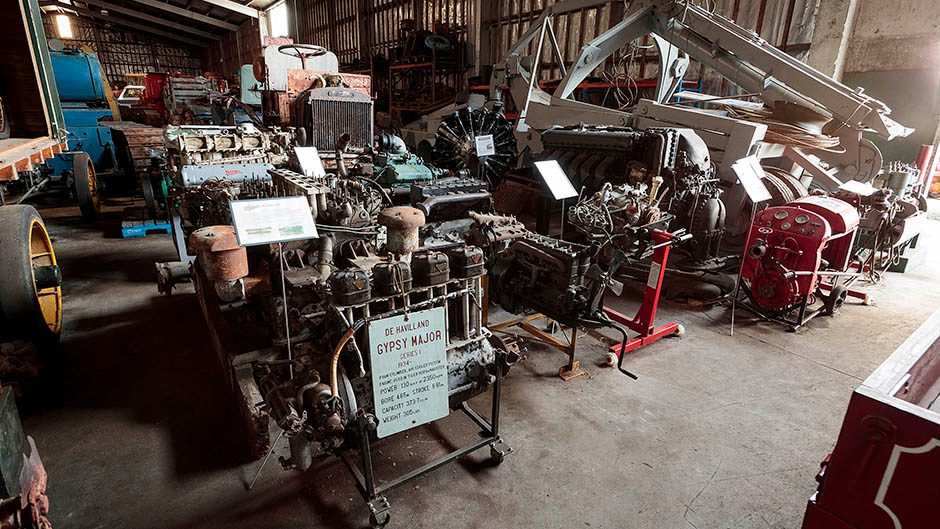

It’s this glamorous era of the brand that first greets you when you enter the four-building museum at Maungatapere. You also get introduced to the thoughts and images of the man who collected most of the Packards on display, Fenton’s late father, Graeme Craw. Graeme’s stated aim in collecting the cars was to map the progress of the 20th Century through the brand. He’d also attempt do the same thing with his large collections of potato mashers, radio equipment, anti-aircraft guns, and historic motorcycles.

As an earthmoving contractor, Graeme also had a soft spot for historic International and Dennis trucks, and Allis-Chalmers bulldozers. When it became known that his former habitats – the family farm at Anawhata and the original Montana winery site on Auckland’s Scenic Drive – had become resting places for rusty machinery, trucks started showing up unasked with many of the obsolete large machines now also on display at Maungatapere. Packards first got under Graeme’s skin during a trip to buy some stock back in 1947.

He spotted a 1923 Packard tourer for sale at the side of the road for fifty pounds. He returned to the farm at Anawhata in the car with 13 sheep in the back after beating the seller down to thirty-five pounds. Impressed by the engineering of that first straight-eight-powered Tourer, Graeme quickly snapped up another 40 Packards over the ensuing six years. For Graeme’s sons, Fenton and Malcolm, this meant that their first drives were Packards.

“Dad gave me a ’47 Clipper to drive first. It was a really rusty car with a six-cylinder engine but I loved it. “It was probably the worst car in the collection, but the only one that he would trust me with at that age.” Malcolm would drive a ’39 Packard to school. “It wasn’t like it was something special, as there were a lot of straight-8s around then, especially the Buicks. Other mates would have Mark 1 and Mark 2 Zephyrs.”

According to Fenton, his Dad was in collusion with an assistant bank manager who helped finance his passion for acquiring Packards. Graeme had sold his original 1924 Tourer in unrestored condition in 1955, and the opportunity came up to buy back the much-restored car, then located in New Plymouth, back in 1974. The asking price was $3500. “He didn’t have the money so he went to the ANZ to ask for a loan. The assistant manager said that his boss wouldn’t approve a loan for ‘an old car’ so they put ‘load of hay’ on the loan documents.

“We were stopped at the top of Mount Messenger on the way back, and a car towing a caravan suddenly came to a halt. It was the branch manager. “That’s a nice ‘load of hay’ you’ve got there he yelled out to Dad.” It’s said that Graeme Craw never liked to chuck anything away, and this has led to two classes of Packard exhibits at the museum.

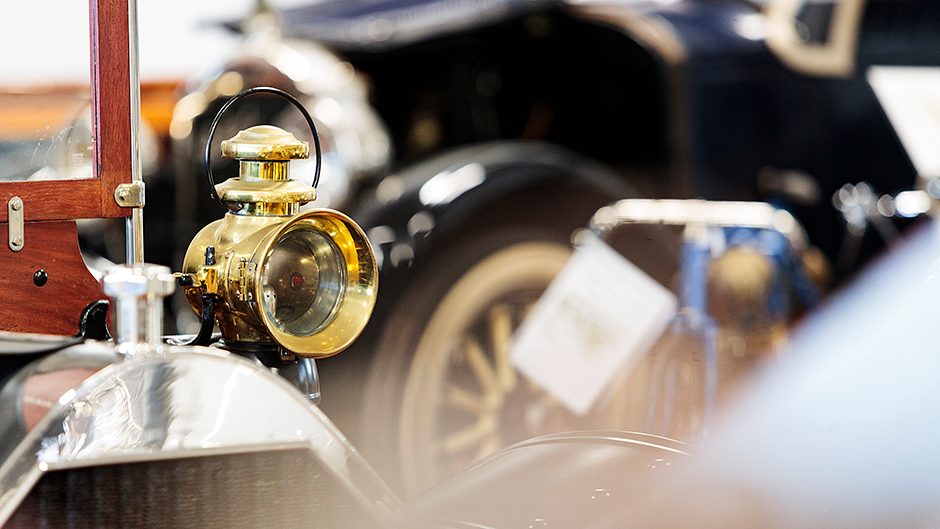

The entrance building has the best cars, including a 1919 V12-powered Opera Coupe that lived on both sides of the law, first as the ride of the governor of Massachusetts, then as a moonshine runner across the Canadian border for infamous bootlegger, William McCoy.

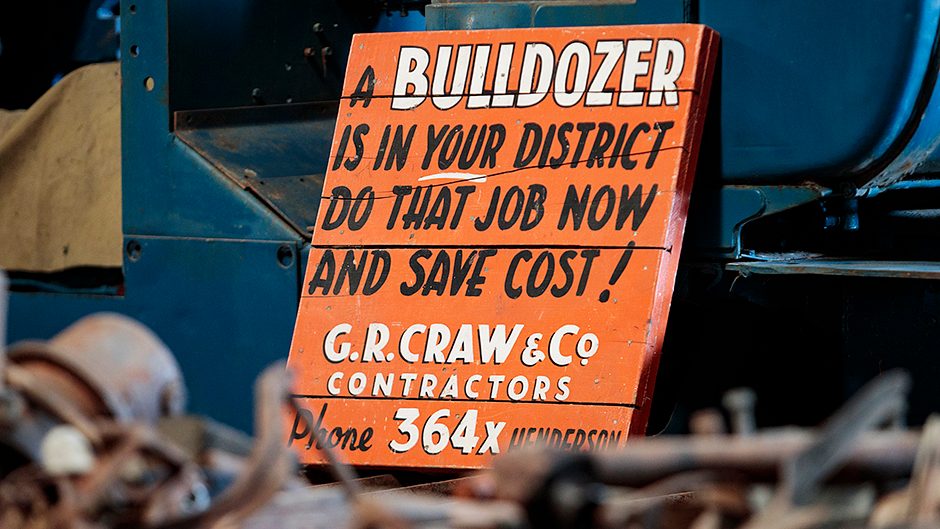

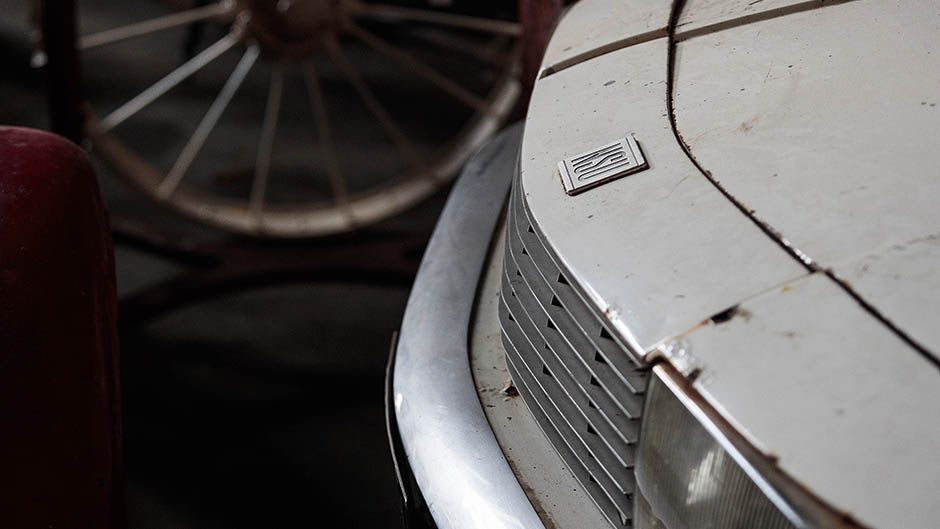

Of more local importance is the ‘single-six’ powered ‘Taurikura taxi’ which served residents of the Whangarei heads from the mid-1920s to the mid-1950s. Perhaps the most beautiful Packard of all located here is the straight-8-powered 1925 Sport Phaeton, complete with a second windscreen and weather protection for rear seat occupants.

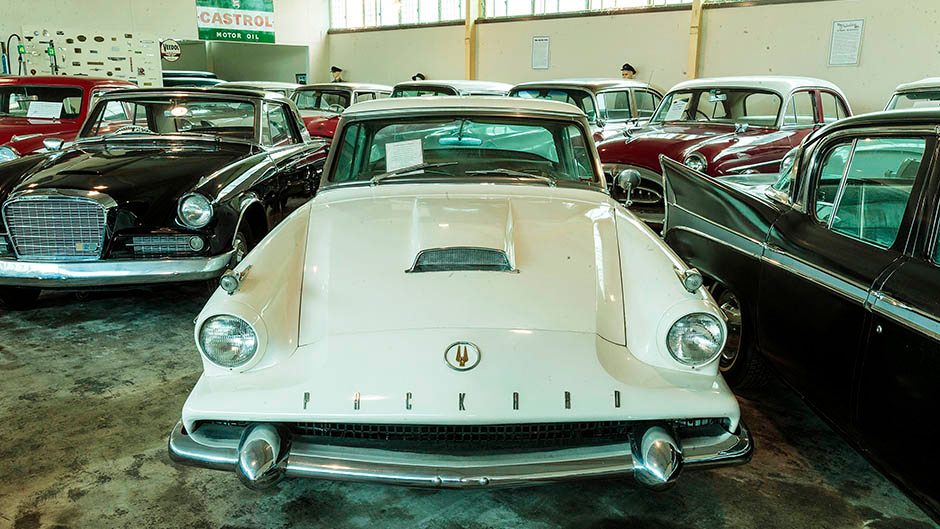

It’s probably fitting that the Packards located in another building aren’t in similar pristine condition, given that they result from the more troubled post-Vincent years for the brand. When Packard bought Studebaker in 1954, the merger was rushed through without full due diligence being paid. The Packard management hadn’t realized that they’d have to make an unlikely 250,000 Studebakers a year for their new acquisition to reach break-even point.

As you enter the second building packed to the gunwales with Packards, you’re greeted by a 1958 Packard Hawk, one of just 588 made. It’s probably the fastest Packard ever thanks to the 205kW developed by the supercharged 4.7-litre V8 engine, but suffers from being perceived as a Studebaker Golden Hawk with a few cheap plastic body parts added for brand management.

Better then to focus on more worthwhile achievements of Packard during the 1950s: the Ultramatic was the best automatic gearbox of its day, and Packard’s perfection of the world’s first limited-slip differential and self-levelling suspension were great steps forward. Unfortunately, the over-reliance on flathead straight-eight engines made the brand look old-school at a time when GM and Ford were producing a deluge of overhead-valve V8s for more affordable automobiles.

Studebaker-Packard axed the latter brand in 1959, and simply became Studebaker again in 1962 with the introduction of the futuristic Avanti, as the corporate association with Packard was considered damaging to the new image.

A visit to Maungatapere is a great way to remember the car maker that powered the air war-deciding P-51 Mustang fighter with its own versions of the Merlin V12 as you’ll find one of these if you search long enough. And it was Packard that gave us the steering wheel, perfected two-pedal driving, and added traction via limited-slip drivelines.

Visitor numbers are growing and opening hours are being extended. Go to www.packardmuseum.co.nz to find out more about the popular ‘start-up’ days.