1970 Renault R8 Gordini

Words Richard Opie | Photos Richard Opie

For South African motorsport fans, the Renault R8 Gordini holds a special place. Arguably a forebear of the modern factory performance saloon, the pair of stove-hot R8’s owned by ex-pat Frans Cronje pay tribute to the beginnings of an entire motoring genre.

Skunkworks. Factory hot rods. Special vehicles. However they’re painted, modified, pumped-up variants of a pedestrian model with a new-car warranty are readily available now. There are AMGs capable of leaving black marks stretching to the horizon, similarly capable high capacity HSVs, while BMW’s M-division offer micron-precise dynamics.

Thanks to the modern media, these showroom rocketships enjoy hero status. Countless Youtube channels draw in the brand faithful, and wheelmen with surnames such as Clarkson and Harris apply handfuls of opposite lock while bellowing “poweerrrr” at the top of their lungs. We’re in a golden age of performance. The hot-up phenomenon isn’t new. Wreathed in glamour and possessed of a certain cachet today, the beginnings of the factory hot-rod were much more modest, created by passionate, innovative engineers in pursuit of the performance edge. These operators personified the engineering of speed.

Comparatively small “backyard” set-ups, their expertise was in extracting every last drop of pace from their chosen marque. As well as being synonyms for performance, they were synonyms for success. The English were epitomised by John Cooper, and his tinkerings with the venerable Mini. In Italy, Carlo Abarth’s wizardry with Fiats came to the fore. In France, Amédée Gordini became indelibly linked to the Renault brand.

While his surname became synonymous with Renault performance, to the point of becoming a wholly-owned subsidiary of the manufacturer in 1977, the Italian-born tuner forged his early reputation before World War II. Displaying an ability to eke eleven-tenths from basic Fiat engines, an association with Simca (then the French assembler of Fiat vehicles) saw Gordini engineering the brand’s motorsport efforts through to the mid-1940s. The 1950’s beckoned, as did a new relationship with Renault. Gordini’s expertise in performance engineering, honed through considerable success in Formula Two, earned him the opportunity to work with Renault in a motorsports capacity.

Renault-Gordini sportscars saw track time at Le Mans, but in 1957 the transformation of the humble Dauphine sedan presaged the future. Available from a Renault dealer, Gordini’s Dauphine packed an 845cc pushrod engine in the back, pumping out around 30 per cent more power than the garden-variety example. Success achieved on the stages and the circuits translated to cars moving from showroom floors. For June 1962 the somewhat bulbous styling of the Dauphine yielded to the boxy Renault 8.

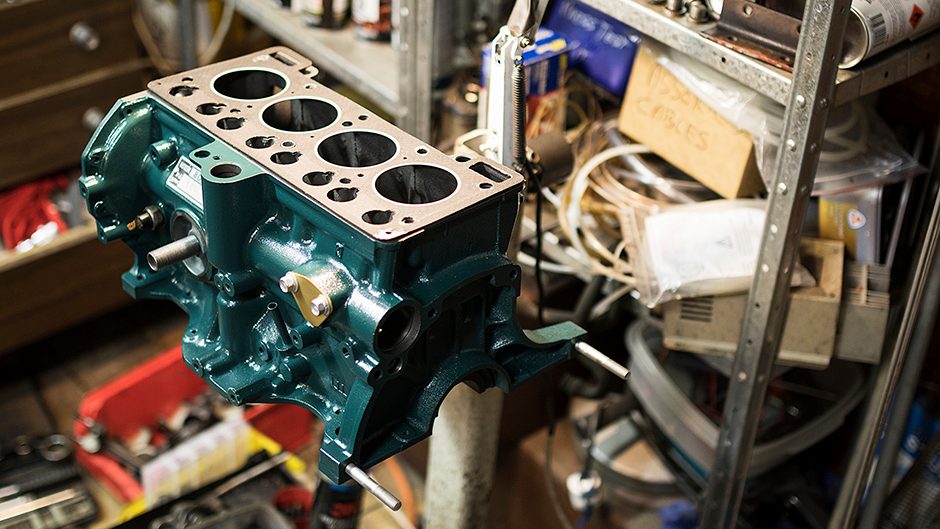

Again flaunting a rear engine, rear wheel drive layout, the compact R8 initially ran a 956cc pushrod “Cléon-Fonte” four-cylinder, upgraded two years later to an 1108cc unit. The upgrade coincided with the development of a Gordini-enhanced version – the latest iteration of Renault’s showroom-available motorsports warrior. As a base, the R8 was equipped with relatively advanced suspension, in the form of a double wishbone front arrangement and swing-axle independent rear end. Road holding was tenacious, and unusually for a car of its size the R8 sported disc brakes on all four corners.

While the hot-rodded options featured uprated springs and fitment of dual rear shocks, the Gordini touch revolved around engine improvements. The standard R8 pumped out a modest 49bhp. Gordini’s iteration of the 1108cc unit almost doubled that, with a relatively impressive 89bhp. Notably, the Gordini-tickled engines featured a bespoke head. These heads still made use of the pushrod-actuated valve system, but were of an improved crossflow design, utilising a hemispherical combustion chamber and a unique “twin-spark” arrangement.

Like any other hemi-head, from the top the spark plug appears dead in the center – but on flipping the head, all that can be seen are a pair of narrow apertures at the chamber’s apex. Cleverly, this innovation split the spark between each half of the chamber, ensuring a more complete combustion and reduced susceptibility to detonation. Naturally this enabled a bump in compression ratio, and with a pair of sidedraft carburettors handling induction and a bespoke set of headers expelling spent gases, the diminutive three-box sedan proved a motorsport force.

Like any other hemi-head, from the top the spark plug appears dead in the center – but on flipping the head, all that can be seen are a pair of narrow apertures at the chamber’s apex. Cleverly, this innovation split the spark between each half of the chamber, ensuring a more complete combustion and reduced susceptibility to detonation. Naturally this enabled a bump in compression ratio, and with a pair of sidedraft carburettors handling induction and a bespoke set of headers expelling spent gases, the diminutive three-box sedan proved a motorsport force.

Three years later, the final form of the Gordini was reached, with 1255cc at the driver’s disposal and an improved close ratio five-speed gearbox with 1:1 fifth. Developing around 110bhp produced at a screaming 6800rpm, the five-bearing steel crank would allegedly keep on spinning right to 8000rpm given enough right foot dedication. Distinguished by its extra pair of driving lights accompanying the bespoke seven-inch headlights set into a frowning frontal treatment, the upgraded Gordini also featured twin switchable fuel tanks and strengthening gussets throughout the monocoque. Colour? Anything you liked as long as it was Bleu de France, the national competition hue, with a pair of white stripes offset to the left from bonnet to bootlid. The story goes that the stripes acted as a visual aid, to provide a peripheral vision reference in the event of spirited, sideways action.

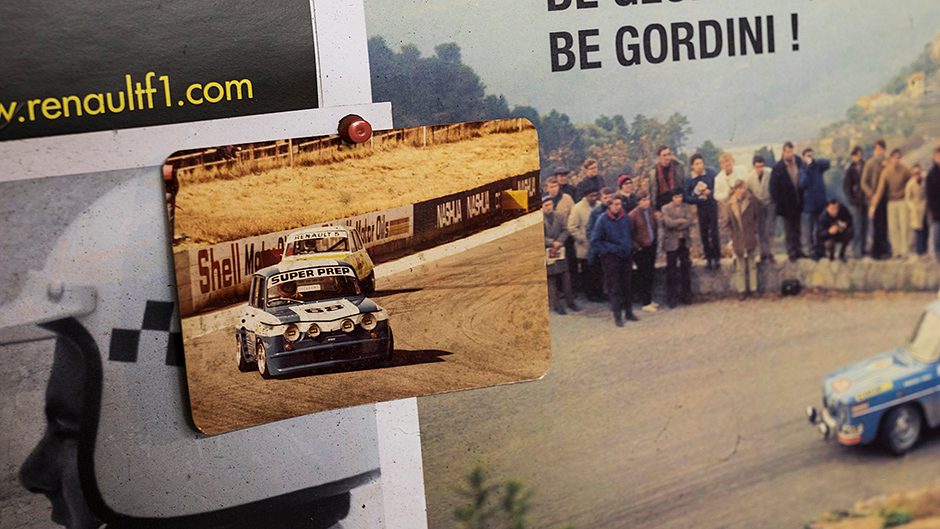

Like the Dauphine forebear, the R8 Gordini tasted competition success. In particular, the South African motorsport sphere saw the rise of the R8 to cult status. Local tinkerers were able to coax great things from the little saloons – among them much revered South African tuning wizard Scamp Porter – and the results told the story. Despite their comparatively small sub-1300cc capacity the R8’s nabbed South African production car titles throughout the late 1960s. In addition to the production races, the modified saloon classes also saw the Gordinis run rampant, claiming the chequered flag against the likes of Alfa Romeo GTVs and Twincam Escort RS opposition.

Like the Dauphine forebear, the R8 Gordini tasted competition success. In particular, the South African motorsport sphere saw the rise of the R8 to cult status. Local tinkerers were able to coax great things from the little saloons – among them much revered South African tuning wizard Scamp Porter – and the results told the story. Despite their comparatively small sub-1300cc capacity the R8’s nabbed South African production car titles throughout the late 1960s. In addition to the production races, the modified saloon classes also saw the Gordinis run rampant, claiming the chequered flag against the likes of Alfa Romeo GTVs and Twincam Escort RS opposition.

Even the Kyalami nine-hour endurance race saw the R8 emerge as the perennial over-achiever. Seven straight years from ’64 through to ’69, the R8 managed top-ten overall placings among rivals including Ferrari P2, Lola T70 and Ford GT40 sportscars.

Growing up as mechanically-minded in late-1960s South Africa, it all becomes strikingly clear why Frans Cronje has something of an obsession for the small Renault, as well as making it go even faster. Having mucked around with cars from a comparatively young age – he was rebuilding engines from his dad’s shed at age 13 for pocket money – Cronje explains his R8 passion succinctly. “It was a giant killer. Who doesn’t love an underdog?”

During the late 1960s and early ‘70s period however, his dream of owning an R8 proved unattainable. The cars were still expensive and Frans had an apprenticeship to complete. His first car was a Mk1 Cortina, and it was here he developed his tuning skills. A Volvo B18 engine swap kicked off a car modifying affliction which he reckons “has never really stopped.” A string of Renaults followed – a 16TS and a modified 4CV, and Cronje’s wife can back up claims that it saw off 3.0-litre Ford Capris between traffic lights with its hot 1100cc, helped by some bespoke-engineered parts.

The Gordini dream persisted, and after a string of garden-variety R8’s and even a turbocharged Renault Caravelle, Cronje finally realised the ambition in 1980, forking out some of his salary as a qualified instrument tech on the factory special. Around 230 of these R8 Gordinis were built in South Africa from CKD kits for the speed crazy market. Cronje’s example rolled into his shed a bent, weathered car showing extensive signs of a hard driven life. Nonetheless it still performed – his wife pinged for speeding the first time she drove it – and for the first 10 years of ownership it had little done to it. In 1989, a three-year restoration process began, with no surface left untouched.

The 1255cc isn’t totally stock standard, yet provided over 40,000 miles of reliable motoring, despite being driven enthusiastically. Capable of a 16.1 second standing quarter, Cronje used the car regularly in South African speed events – “we were hoons, really, doing sprints and gymkhanas every month.” Gearboxes (now a rare commodity for a Gordini) and clutches were the usual victims, and Cronje describes the driving style as similar to an early Porsche 911.

“The nose is light, it changes direction easily. The rear however grips hard, until it breaks away. There are two rules to racing an R8. Number one; you don’t lift in a corner. Number two; you don’t lift in a corner.”

Trail braking is a no-no, the R8 rewards early braking and power out of the corner. Until shifting to New Zealand in the early 2000s, being driven hard was all the car knew. Shortly thereafter Cronje admits he became aware of the car’s value, as well as the amassed stock of spare Gordini heads and unobtanium five-speed gearboxes. Around 14 of the cars remain on the road in South Africa. But in a Kiwi context, Cronje owns the solitary example. Appeasing the need to race a classic Renault was always going to happen.

Forking out $80, Cronje bought a second example in 2007, currently undergoing repairs in his basement workshop. Complete with a spares car, the Petone-built example has seen a transformation into a Gordini-clone. Outwardly the replica sports the Gordini headlamps, small wheel arch flares and obligatory French blue paint. Drawing on experience gained while racing and engineering a particularly special R8 in South Africa (a faded photograph hangs over the lathe), Cronje set about improving performance to be competitive in the Auckland classic race scene.

Forking out $80, Cronje bought a second example in 2007, currently undergoing repairs in his basement workshop. Complete with a spares car, the Petone-built example has seen a transformation into a Gordini-clone. Outwardly the replica sports the Gordini headlamps, small wheel arch flares and obligatory French blue paint. Drawing on experience gained while racing and engineering a particularly special R8 in South Africa (a faded photograph hangs over the lathe), Cronje set about improving performance to be competitive in the Auckland classic race scene.

Uprated suspension and brakes, the latter a necessity due to the rarity of parts, enable the Renault to stop effectively and characteristically lift the inside front wheel exiting corners. A locked diff, with output splines machined on his own equipment transmits power to the fat semi-slicks. Engine wise, it’s all Gordini. The necessary head tops the cast-iron block, internally Cronje uses Venolia custom forged pistons modelled off a Fiat item, pocketed for valve clearance. Displacing 1450cc with a rev limit of around 7500rpm, Cronje estimates the shed-built pocket rocket produces around 130bhp breathing through 40mm Weber carbs. Specially built headers top off the mechanical package, and while the car is currently in the midst of repairs Cronje can still be found – often on 3 wheels – among the ERC (Euro Racing Classics) fields.

While Cronje’s pair of glorious Gordinis may seem light years from the latest AMG or BMW M hardware, buried beneath his home in a proper car-guy workshop they pay homage to the origins of the factory hot rod.