Rod Tempero motor body builders- traditionally Tempero

Words Richard Opie | Photos Richard Opie

Tempero motor body builders, this country’s most lauded proponents of doing things the traditional way, is a homage to family and an era where beauty and function co-existed in harmony from workshop to tarmac.

Stepping out of the sunlight and into bright, airy environment of Rod Tempero’s Oamaru workshop seems a far cry from your run of the mill “chicken shed”, as it has been colloquially termed. In fact, the vast expanse instead strikes a middle ground between the past and the present. Modern steel beams and corrugated cladding juxtapose with ranks of shapely motoring hardware spanning the 1950s and 1960s, an era of vehicle with which Tempero has doubtlessly aligned himself and his craft.

Immediately, there’s a sensation of stepping amongst something special. An aura of the past hangs thickly among the still workshop air, not only by virtue of the exquisite form recalling a sports car golden age, but the time honoured techniques used within. It’s a fitting vibe for Rod’s workshop, formerly known as Rod Tempero Motor Body Builder, which assumed its contemporary form around ten years prior. The South Island coach building dynasty was formed way back in 1946 at the skilled hands of Tempero’s grandfather, Alan.

Even before the outbreak of the second world war, Alan Tempero had honed his craft before departing to serve in both the Pacific and desert conflicts. In 1946, once global turmoil had settled and the nation was again humming to the sound of industrial prosperity, Alan set up the original Tempero workshop in Tee Street, Oamaru. Construction of commercial vehicles proved the initial focus. Workmanlike nameplates of Bradford and Fordson (among others) drove in naked, exiting wearing specialist coachwork befitting their intended purpose, soon to be joined by production of his own line of caravans.

In 1953, Alan’s son Errol came on board continuing the caravan trade, but also assisting with the development of Government specified work, which would become a Tempero staple; even today, International A-series and Holden 1-ton ambulances survive to tell the story of the Tempero motor body legacy. In 1978, the third generation of Tempero coach builder joined the fold. Having been a regular school-holiday fixture in the workshop during his younger years – usually on the end of a broom – Rod explained that at that stage he “really wanted to be a motor body builder.”

While the commercial focus of the business was still reliant on the utilitarian rather than the elegant, Rod did mention that throughout the years each of the senior Temperos did dabble in the sports car spectrum.

Coach work for vintage cars, as well as local racers, briefly interspersed the bread-and-butter work. Errol built his own Ford “Easy Roll” based sports car, as well as the AV Special for a colourful local, which was based unusually around French Avions Voisin running gear. But in 1980 a build rolled from the Tempero workshop, by then located in Wansbeck Street, that would alter the destiny of the family business. Rod describes it almost casually. “I was a member of the local Sports Car Club, so dad suggested we build a car. After scouring his books, I decided I liked the D-Type Jaguar. So we built one.”

The D-Type was wheeled from the workshop for Rod, then still a teenager, to drive as a road car. Owing to decades of expertise hand-shaping the exterior panelwork, the D-Type’s inch-perfect bodywork proved an unquestionable attention grabber. Both local and international automotive media picked up on the creation. This resulted in sufficient interest that the scratch-building of faithful replications of period sports and GT thoroughbreds grew to be a viable business. Throughout the 1990s, the ‘Wansbeck Workshop’ saw Errol and Rod produce vehicles to order – almost constant was the 1950s through ‘60s period focus – including no less than 46 D-Type Jaguars of varying specification, all built on the reputation earned by that very first car.

A quintet of XJ1 sports prototypes also left the workshop. Lister Jaguars, one-off HWM Jaguar specials, Italian-inspired racers and even Aston Martin DBR2 recreations all rolled from the Wansbeck Street workshop doors, each one building mystique behind the Tempero legend. In 2003, following a shift to a new Dee Street location, Errol had made the call to sell the business. While Rod stayed on for a few years working for the new owners he inevitably went out on his own to create the form Tempero Motor Body Builders has assumed today. It was 2007 and the ‘chicken shed’ urban myth was born, just South of Oamaru on State Highway 1.

The Tempero badge, hanging unobtrusively from a roadside sign is the only giveaway of the craftsmanship within, and from the front shed Rod kick-started his own spin on the family legacy with the build of a 1952 Maserati A6GCS Berlinetta. With all Pininfarina-penned lines present and accounted for, the Maserati set Rod in good stead for future endeavours and attracted its own share of media attention.

Coined by an Otago Daily Times writer, the ‘chicken shed’ moniker, while technically correct probably paints a mental image more ramshackle than the actual reality. The original sheds, while used commercially for poultry purposes, present a scene more aligned with a traditional country workshop. Along the north facing wall in the original shed, a line of wheeling machines (Rod explains that only Americans call these “English wheels,” possibly too many reality TV shows are to blame) stand resilient, a stoic reminder of the way things used to be done.

It was with a single wheeling machine, a folder and guillotine that Rod commenced his own enterprise. Workshop machinery he explains is the basis of any motor body building workshop. As the business grew, more work was taken in-house. Where machining work was once farmed out locally, lathes and mills have been added to the Tempero arsenal over time, taking up residence down the end of the new shed, added only three years ago to accommodate growing demand.

There’s now a modern spray booth squeezed down the back. British Racing greens and Rosso Corsa reds can be applied to freshly beaten panels, further enhancing the Tempero ability to turn out a product meeting precise customer demand. For all the addition of slightly more modern equipment, the overarching feel to the Tempero workshop remains wistful. It’s not the clinical, sterilised environment of the modern dealer workshop.

It would almost be a shame to find polished floors and gleaming, modern equipment all categorically stacked away in place. Instead, the Tempero workshop is a welcome, dare I say homely place for the vintage-curious to explore. As well as traditional tools placed haphazardly among the workshop, every corner reveals a nostalgic revelation. Be it a stack of reference material weighed down by a battered panel beating dolly, or signage reminiscent of the older Tempero workshop quietly gathering dust, it all feels so right.

It’s not only time-worn gear lying around that lends to the traditional aesthetic. Names like Weber and Borrani scatter the various surfaces of the workshop. Brand new, but period correct parts (and associated packaging) used on several Tempero builds, like the recently completed Maserati 250F GP racer and perhaps one of the best recognized recent projects, the 250 GTO Berlinetta. For the weekend tinkerer, the process involved in creating a Tempero recreation appears daunting.

Rod explains the process like any of us might consider doing a basic service. Commissioning a build is as simple as making contact, and like the craftsmanship, many clients prefer the traditional approach of walking right in the front door. Rod reckons around two and a half years later a finished car sees daylight.

Initially, research is conducted. Reference material takes many forms, from long out-of-print books to obscure internet images, all typically period photos to ensure authenticity. Rod scales from these images using known dimensions, creating a drawing which is then offered up, 1:1 scale, to the blackboard. The build table is then offered up to the blackboard, which is where the physical build begins to morph.

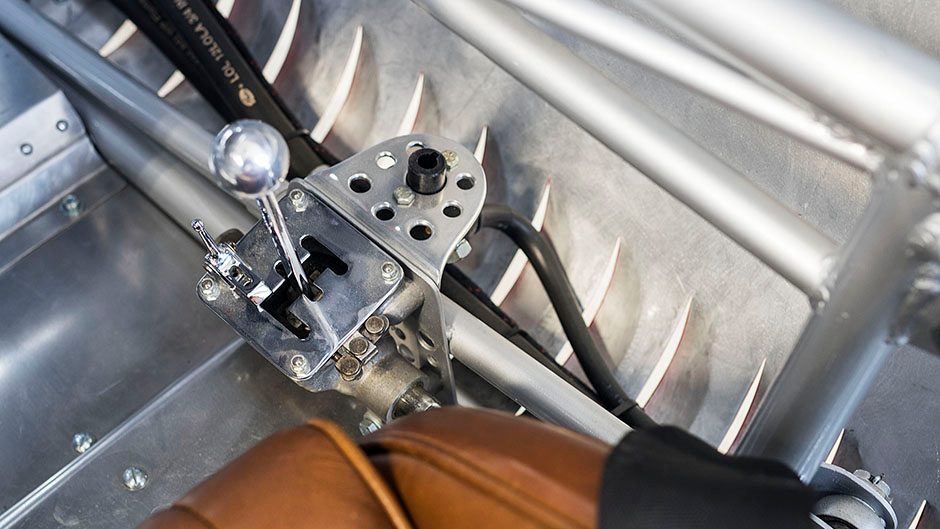

Beginning with basic chassis construction (such as a D-Type monocoque, a spaceframe like an Aston Martin DBR2 or a Berlinetta oval tube chassis) mechanicals are added to the mix, typically sourced from donor vehicles or acquired independently as reproductions or restored original components. Wheels and tyres are placed in their correct position, maybe the best indicator of final proportion. With the visual of the full-size drawing matched to the location of the vital mechanicals, wooden bucks are then created to fit over the vehicle’s inner workings.

Hand cut from plywood, from this point Rod mentions the rest sort of follows suit. Reliant on the center line of the drawing as well as the wheel arch curves, predominantly aluminium panels are hand rolled, tweaked by eye and finally applied to the buck, cut back to weld lines and gas welded together. Of course, final finishing can take place off the car, while the mechanicals are pieced together and finished, which also feature chiefly period techniques and components to tie the package together.

Items like steering wheels are manufactured to suit, with watercut centers polished in-house and sent away for installation of wood rims. Peeking into the cockpit of the 250F, even instrumentation is kept consistent; in that instance, even down to the bespoke mechanical tachometer. It seems set to continue. On our visit, there were no less than five cars in the build process. A couple of D-Types, a rebuild of one of his father’s early builds damaged while competing on the Targa, a Dino 246 GP car and another special roadster sporting an oval-tube chassis on the build table.

Now with five staff on hand to help (including apprentices), I posed a question possibly difficult to quantify given the pursuit so firmly rooted in recreating the past. What does the future hold for Rod Tempero and the ‘chicken shed?’ He pauses; it’s a difficult one indeed. “The selling point of a Tempero recreation is the build process,” Rod explains with a wry smile. After nearly 40 years in the business it’s clear the master craftsman enjoys creating. Expect more masterpieces from the unassuming North Otago workshop, helping to keep alive the mechanical symphony of both period mechanicals and the hammering echoes of a craft still practised by a dedicated few.