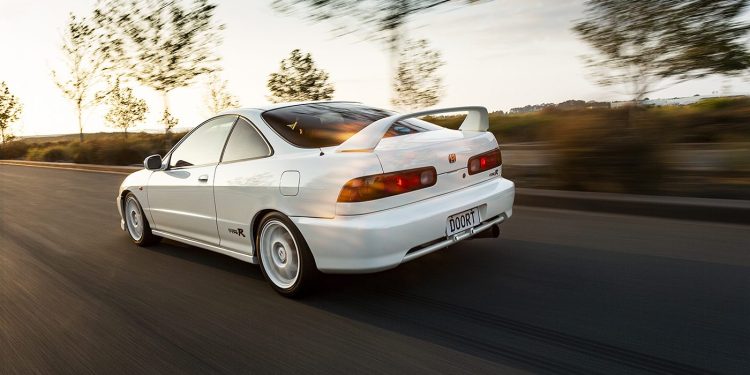

2000 Honda Integra Type R

Words Richard Opie | Photos Richard Opie

In the car sphere, the letter ‘R’ brings with it a certain expectation. R is for race. We delve into one of the most celebrated Hondas of all time, the knife-edged Integra Type R.

Imagine your favourite back road blast. The route you take early on a Sunday morning, when the ‘normal’ people are only just beginning to consider starting their day with a single origin Fair Trade brew. You’re snug between the bolsters of a seat that’s designed for purpose. The tacho needle leaps for the ‘9’ on the gauge face. Just forward of the firewall, the mechanical crescendo is transcending from a howl, to a shriek. The next gear is selected with a deft flick of the wrist. Hard on the brakes, down a cog, clip the apex, and power out as the needle again rockets clockwise towards the red. This is grin-inducing stuff. This is how to experience the first-gen Honda Integra Type R.

Notable Japanese cars from the 1980s and 90s are now very much reaching maturity as bona fide “collector” vehicles. They are coming to prominence as a generation of ‘maturing boy racers’ are now clamouring to get their petrol-head mitts on some of the icons of their formative years. They represent a special time in Kiwi car history, the golden era for the ‘import’ scene (itself a term borrowed from the USA).

Cheap and ready access to a swathe of performance cast-offs ex-Japan defined a generation of Kiwi car nuts. Names like Skyline, WRX, Evolution and Familia would come to epitomise the street scene of the time. For those with a penchant for highly strung, naturally aspirated performance, the brand with the “H” on the nose became the default choice.

Honda had become synonymous with small-capacity, high-revving engines that punched well above their cubic capacity. Early on, Honda incorporated motorcycle engineering techniques into their tiny S-series sports cars and sporty saloons. DOHC heads, quad-carburettors and high redlines characterised these cars in the early 1960’s, and as the sun set over the 1980s, a new innovation gave Honda the edge in small engine performance.

Four simple letters debuted along the flanks of the second-generation Honda Integra in 1989. The DA6-chassis Integra XSi would be the first to employ Honda’s “creatively” monikered Variable Valve Timing and Electronic Lift Control, known as VTEC.

Marketed as “two engines in one,” VTEC worked by incorporating two separate cam profiles, a less-aggressive “mild” one aimed at maximising low RPM response and tractability, while a second cam profile with increased lift and duration was targeted at top end performance. At a defined RPM value, VTEC would hydraulically switch from the low to the high cam profile, transforming (in the case of the performance engine variants) a proverbial kitten into something of a howling tiger.

That 1.6-litre ‘B16A’ pumped out an impressive 119kW, and lived through to the early 2000s, reaching it’s 136kW development zenith with the EK9 Civic Type R. Honda wasn’t about to draw the line at 1600cc however. In 1993, the 4th generation Integra was launched in Japan. Carrying the prefix DC (3 door coupe) or DB (sedan), the hero model of the range was known as the ‘B18C’. With extra capacity, the 1.8-litre variant blessed the new Integra with 131kw out of the box, not to mention a dollop of useful torque over and above its B16A cousin. That’s the tedious stuff out of the way.

In 1995 Honda dropped an instant classic. Symbolised with a bright red ‘R’ on the rear quarters, the Integra Type R brought all of Honda’s competition engineering nous to the masses, as an affordable, uncompromising package. Three years earlier, the Japan-only NSX Type R debuted. Intended to address some of the regular NSX’s foibles, the R shed around 120kg, featured aggressive suspension updates and topped the package off with a hand-built, blueprinted variant of the 3-litre V6. Likewise, the DC2 Integra Type received similar treatment. The already jewel-like B18C was given the hand-built treatment by Honda’s specialist team. In its JDM form, the B18CR’s (unofficial designation) output was a shade under 200hp, thanks to lighter conrods, revised inlet valves, molybdenum coated pistons, more aggressive cams and a larger throttle body. Spent gases exited via a tuned-length header, with a full-stainless exhaust running the length of the car.VTEC “kicked in” at 5800rpm if you had an earlier car, and 6000rpm for the later (98-spec onwards) cars. The pint-size powerhouse would rev all the way to 9000rpm, with a cacophony of intake roar and exhaust howl, unabated by sound deadening to save weight.

The Integra Type R tipped the scales at 1080kg, although later iterations with ABS and airbags were heavier. Chassis reinforcements, such as extra spot welds and thicker steel around critical areas stiffened things up while lower, firmer suspension and beefier antiroll bars honed the handling. Externally, the facelifted styling featured a subtle front splitter and mandatory-for-the-90s high rear wing, while inside a pair of Recaro SR3 seats in red or black Alcantara, a matching rear seat and Momo steering wheel set the R apart.

Accolades flowed from the press, and in retrospective reviews the hyperbole was even more prominent, regarding the DC2 “R” experience. So what about that?

Opening the driver’s door to a DC2 R sets an underwhelming scene. A flimsy door handle, a hollow clang as it closes, it’s all very “low rent.” Settled into the Recaros, there’s black plastic everywhere, punctuated by dashes of faux carbon trim and that very special 10,000rpm tacho. Everything you need, nothing you don’t. The chunky Momo sits at the ideal height while the seat is low enough that the driving position feels purposeful. Dawdling about at low speeds, you could be fooled into disbelieving the hype about the B18CR. Below that magic 6000rpm threshold, it’s standard hatchback stuff. But the moment the solenoid activates and sends the high-cam lobe into action, Mr. Hyde is unleashed. To quote Evo magazine, “its demeanour is manic, joyous.” The 6000rpm change point may sound high but thanks to that screaming redline and a sublime-shifting close-ratio five-speed, it’s relatively simple to maintain a head of steam.

It’s an overall frenetic, tactile experience. Booming road noise permeates the cabin while every stone ricocheting from the underside is a snare drum crack. The B18CR creates a mechanical clamour so addictive, the accelerator can’t be depressed hard enough. And then the corners loom.

The steering deserves initial mention. It’s immediate, communicative. But at the same time it’s smooth, with a little over two turns lock-to-lock ensuring hairpins are negotiated with ease. The front tyres share a direct line to that chunky grip, letting the driver know exactly what’s going on beneath them. On the topic of grip, there’s plenty of that. These cars had fairly small tyres by modern standards, but the revisions to the double wishbone suspension work them to their maximum. Ride is reasonably compliant, though can be a little crashy by virtue of the stripped-back character. But its purpose isn’t comfort.

Pitch the car into a corner a bit too hard and the back end will progressively begin to slide. It’s no cause for alarm. The antidote is a quick stab of the throttle and the helical LSD ensures the front wheels pull the R back on line with nary a hint of understeer or torque steer. In contrast to modern hot hatches, the Integra Type R is analogue to the core, almost rudimentary. It’s a car that offers very little compromise, a prescription that, with present-day concessions to comfort, emissions and safety, is lacking in most showroom offerings today. It’s the moment Honda let the world know they too could foot it on the back roads with the best Europe could offer.

As Dickie Meaden of Evo magazine surmised when the DC2 Integra Type R topped their list as the greatest FWD of all time, “it’s a car as sweet and all-consuming as I’ve experienced at any price, and as pure and focused in it’s own way as any Porsche RS. Forget the accolade of greatest front-wheel drive car. The Integra Type R ranks as one of the truly great drivers cars of any kind.”

Perhaps in a Kiwi context, it’s a sign the boy-racer is growing up. The 90’s icons are coming of age, and making their mark as automobiles of desire. A new era of classic cars is dawning, and among it is a swathe of NH0 Honda Championship White.