The Citroën conservatoire- Citroën’s sanctuary

Words Peter Louisson | Photos PL

Not far from Paris, in Aulnay-Sous-Bois, is the world’s most comprehensive Citroën collection, with over 400 vehicles on site, the earliest dating back to 1919.

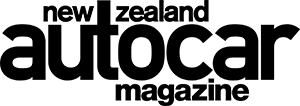

The vehicles in Conservatoire Citroën, which opened in 2001, are arranged in various groupings, including those dedicated to sport and adventure. The first area upon entering the museum proper hosts the earliest offerings from the brand. Concept cars and prototypes are scattered about the place. Also on show are some LCVs and unusual offerings, like presidential cars, half tracks, helicopters and other oddities.

A bust of André-Gustave Citroën, the founder of the firm, takes pride of place at the museum entrance, as does a huge fishbone-like gear device called the chevron, long the symbol of the brand. Citroën studied engineering in Paris and in 1900 bought a patent in Poland for the chevron gearset. This was considered a more efficient and reliable way of turning wheels in textile plants than belt drive, and was able to transmit far greater forces. However, the machinery for making them did not exist in Europe at the time so in 1912 Citroën travelled to America to buy the necessary tooling. There he met Henry Ford and was introduced to the concept of scientific management as espoused by Taylor, ideas that Henry Ford incorporated in the mass production of cars. In 1914 Citroën became embroiled in WWI and his nascent factory was converted to producing artillery shells.

After the war he decided to produce an affordable everyday car that would compete head-on with Peugeots and Renaults of the time. His first vehicle, imaginatively known as the Type A Citroën, launched in 1919. Most cars of the day were sold as a rolling chassis with the body work added later. Citroën produced his first car fully built up and charged less than the opposition. Successive new models would always include technological innovations.

The Type A was manufactured for two years and succeeded by the type B in 1921, of which there were 25 different versions. The B2 built on the B1 with electrical headlights and self-starter, and the steering wheel on the left. It was intended primarily for farm work, and also for leisure. The B2 proved both robust and reliable. This version, the B2 Landaulet was the one to be seen in for it was chauffeur driven with the driver outside the cabin. It became a medic’s favourite and was nicknamed the “doctor’s coupe” because it had a high roof so physicians didn’t have to remove their hats during travel.

The B10 was a fully metal car, with no parts constructed of wood, its manufacture incorporating a new welding technique that’s still in use today. This was the first car in the world to have cable- operated brakes, employing a patent from Westinghouse. It also had power steering. Early French cars had rear brakes only.

When the B12 arrived, underpinned by this chassis, it had front brakes installed, with the foot brake on the right and the accelerator in the middle. Note also the ingenious location of the gas tank sited above the pedals. After Type B came the Type C in 1928, depicted here as a 1929 luxury model with running boards and wider tracks, required because it had a six cylinder engine with more power. Called the AC6, short for Andre Citroën six cylinder, this coupe version was owned by a famous author, Sasha Guitry. It had a sliding window separating the driver from the passengers.

The 1933 Rosalie introduced the floating engine, by virtue of rubber engine mounts, the patent bought from Chrysler. It was also a luxury car that didn’t rock around, gliding like the swan and hence the hood ornament. In 1934, Citroën kind of outdid itself with technological breakthroughs, introducing the Traction Avant. This pioneering vehicle was the first mass-produced front-wheel drive car, with almost three-quarters of a million made between 1934 and 1957. It also featured a hydraulic braking system and unitary body.

The Traction Avant had a notably low centre of gravity for enhanced stability and managed 90km/h, quick for the time. However, the expensive development process brought the company to its knees in 1935, and it was subsequently purchased by Michelin who managed Citroën until 1974. Peugeot then bought it from Michelin. On 2 July 1935 Andre Citroën died from stomach cancer during the downfall of the company. Evidently he had been hit hard by the death of his explorer friend, Georges-Marie Haart in 1932.

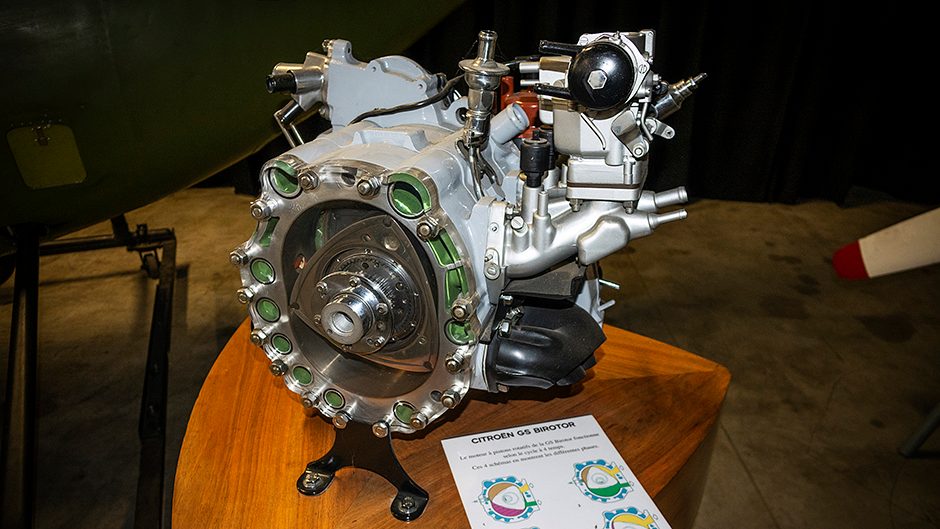

At the beginning of WWII, the 2CV was conceived, described as, a “tres petit voiture” or very small car. After just 258 units had been produced the state ordered all of these units to be destroyed since German spies were taking an unhealthy interest in this model. Four units were hidden in an attic (J) and were only discovered 10 years ago. They are now on display in as-found condition.

The interior was pretty basic, as was the tiny horizontally opposed twin-cylinder engine. This specially modified B2 was commissioned by Tsar Nicholas II from Russia. He hired a French mechanic, Kégresse, to design a vehicle that could be used during the Russian winter when the roads turned to mud. Kégresse invented an ingenious caterpillar system that could be mounted to any type of vehicle. It was affectionately known as the “Golden Beetle”.

The Frenchman later returned to Citroën and George-Marie Haarte asked to use the half track in one of his expeditions. In 1922, a P19 B2 type crossed the Sahara Desert in 21 days, a trip that would have taken six months with camels. This was the first motorised crossing of the Sahara. Another group, also including Haarte, crossed the Gobi, said to be the least friendly of all deserts. They arrived in Hong Kong where Haarte unexpectedly died from pneumonia.

This is a special 2CV model designed specifically for the armed forces and fire protection folk for driving in extreme terrain. It featured an engine at each end, both being 425cc twin-cylinder 13.5hp units. There are very few left intact and approximate cost today is 250,000 Euros. There were numerous 2CV one-offs made, this a Bond car with a GS 1100 engine. Roger Moore drove this car during the shoot of ‘For Your Eyes Only’. The ‘bullet holes’ are decorative add-ons. Also in the museum is the oldest DS, which debuted at the Paris Motor Show in October 1955.

A successor to the Traction Avant, it introduced aerodynamic styling and hydropneumatic suspension, not to mention the first implementation of disc brakes. Production continued until 1975. The DS was popular amongst Citroën employees because it was the car that delivered the pay to the workers, the cash carried in the trunk. Evidently on the DS options list at some point was a safe. Here I get behind the wheel of a breezy 1968 example DS. This is a pedal car that was part of the deal if the parents bought a Citroën.

It had an electric motor, forward and reverse gears and a headlight for night work. Nowadays they’re said to be worth 15,000 Euros. This particular example was modelled on the original C4 of the late 1920s. The Citroën DS21 won the Monte Carlo Rally twice, its superior engine power, stability and swivelling lights said to be contributing factors in its wins. The iconic Mehari (S), from 1969. The lightweight offroader was based on the 2CV, and produced for 20 years from 1968. A good condition example like this is worth around 15,000 Euros.

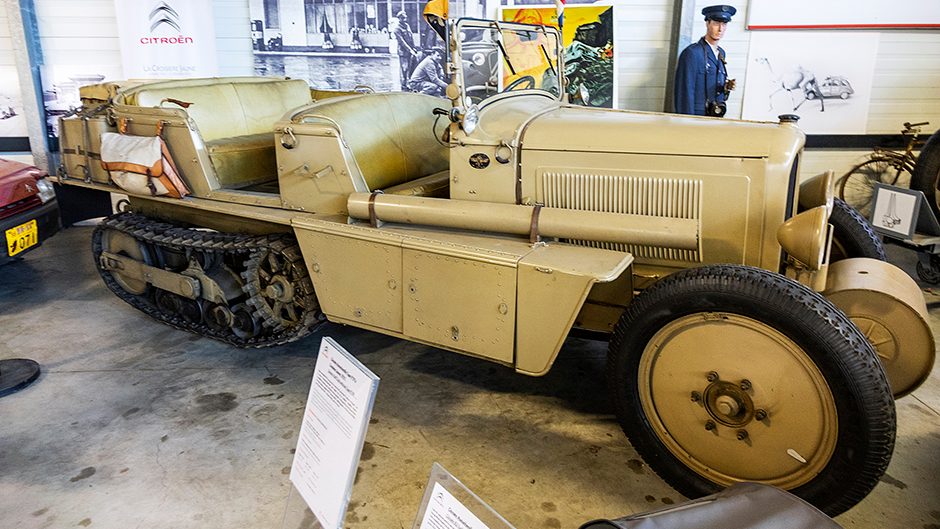

The original parts are still available because a Frenchman bought the tooling machines. In 1974 Citroën manufactured a rotary engine which pushed a GS to a top speed of 174km/h. Just 847 were built but the energy crisis put paid to its prospects because the rotary had a notable thirst for hydrocarbons. The twin-rotor engine was also used to power an RE2 helicopter but the project never got off the ground because production of the rotary ended before the chopper took flight. It flew 40 hours but never made it into production for political and industrial reasons.

Also in 1974 production began in a new plant of the CX which featured an unusual production step in which the car body was dropped over the top of the chassis and bolted in place. It too featured hydraulic suspension, and a transverse engine layout. Hallmarks of the CX were superior comfort and stability. Charles De Gaulle’s presidential car was essentially a modified and stretched DS21. De Gaulle is said not to have liked it much because he was isolated in the back and unable to converse with the driver, except by opening an oddments box. He preferred to drive his own black DS19. The latter wasn’t an armoured car though perhaps it should have been, given a narrow escape from an assassination attempt in 1962.

There were evidently 30 attempts on his life, all failing; he died from a heart attack while watching TV in 1970.

The first LCV from Citroën was the Tub (Y), a front-drive machine. It was aimed at farmers and the self employed and went into production in 1938, though manufacture stopped in 1941 during the war. It was used extensively by the army and hospitals as a medical transport vehicle. Notably, this was the first LCV with a sliding side door.

This Type H is an LCV with a 2CV engine and front-wheel drive, produced from 1948 to 1981. Its origins are obvious; note the 2CV headlights. It is very sought after by food and beverage merchants, even today, because of its retro styling.

Over 500,000 were produced in a range of body styles. One of the many concept vehicles on display, this six-wheeler was never put into production. It harked back to the half-track machines produced for all-year-round work in harsh Russian and Canadian environments.