1987 BMW 325i Group A – The Rat and the BMW

Words Stu Owers | Photos Tom Gasnier

Stu Owers reunites Paul Radisich with one of his first touring car mounts, the ex-longhurst JPS BMW 325 Group A racer –

And also bags himself a drive.

It’s hard for me to reconcile the two sides of Paul Radisich. The one I’m talking to in the pits of Hampton Downs is softly spoken and modest. His whole demeanour reminds me of a relaxed and suavely charming diplomat. After each of my questions he hesitates momentarily, considering his reply. His answers have a weight to them. He has never been known to boast or shout about his talents, so if there is an inflated ego within, it’s well smoothed over. Like always, today he is immaculately dressed. He still looks racing fit and much younger than his 50 years.

I have to remind myself that this impeccably mannered and courteous guy became a world champion during the most aggressive and combative period in modern motorsport. Kiwis watching on TV back in the ’90s saw this driver shine during the era of push-and-shove sedan racing. Today, that rough-and-tumble environment has largely been diluted by officialdom, and now any pushing on the track has to be pretty subtle. But back then, the cars from the British Touring Car Championship rarely finished a race without significant panel damage, and several drivers would have been punted into the barrier. It was quite normal to flick or barge another competitor out of the way if you couldn’t complete a normal pass. Because of the television coverage, the style of racing also caught on here for a while, and it became a horribly expensive time for many local drivers before it was stamped out. That brutal type of competition was already established in Europe by the time Paul arrived, but he certainly didn’t shrink away from it, and gave out as much.

We were at Hampton Downs to get Paul’s impressions of the Group A car he drove in the Wellington Street race series back in 1987. I opened the door for Paul and asked him to climb in for some photos. ‘Hey, it’s exactly how I remembered it,’ he said. ‘Even the original door panels and the standard rubber pedal covers are still here. This was a great little car, so nimble and balanced.’

He moved the gear lever around. ‘I think we had to be careful with this gearbox. It was a little bit delicate, if I remember correctly. Huh, look at this: a very wide gate and long throw, just like a standard ’box.’

Of the roll cage and safety gear, Paul noted, ‘Nowadays the door intrusion bars would be much higher, and, of course, we would also have a window safety net.’ He reached up to the ceiling. ‘Look, it’s still got the original roof lining. You couldn’t do that now because of the fumes [in the case of a fire].’

It was time for Paul to get changed into his race gear for some laps so he could get the feel again for the car. As he headed out on the track, we could enjoy the six-cylinder exhaust note. Though certainly not the distinctive high-pitched scream of a four-pot M3, it’s melodious all the same. We watched Paul circulate for several laps and then heard the exhaust note changing back to an uneven popping burble as he eased back beside us in the pits. It was now my turn.

I’ve driven faster race cars, but the memories of the Group A era have a magic aura. It was all about intense racing by big international names in vehicles that seemed incredibly similar to what you could buy in the showroom. I’ve always wanted to know what a real Group A car would feel like, and this was a chance to step back in time.

Paul leaned in while I was getting strapped in and explained the gearbox. ‘It’s a dogleg first, down to the bottom left. The rest of it is a normal ‘H’ pattern. Take it slowly, though; don’t rush it.’ Garry then explained the starting procedure. The combination of an old-style fuel injection system and a race cam meant that the car didn’t like low revs, so I was to keep the revs up and slip the clutch to get it rolling. With the engine stuttering, I hobbled down pit lane and out on to the rolling Hampton Downs track.

The first thing that struck me was how close the gear ratios were; this was no standard gearbox. It kept the revs perfectly within the power band but it needed constant gear changes. The big surprise was how tall first gear was. Two of Hampton’s corners are normally taken in second gear, but in the BMW it was all the way down to first. While I missed more than a few apexes because of the heavy steering, the car felt light and surprisingly fast. The handling balance had a slight rear bias towards oversteer, so I imagine you could have some real fun drifting this car around. The all-round vision was superb, unlike the closed-in, claustrophobic feel of modern racing sedans.

It didn’t show any of its 26 years and remains a very driveable race car, even by today’s standards. The car came with the original Frank Gardner suspension setup notes, and it’s kept in the same trim as it was originally raced by Tony Longhurst. Back in the pits, Paul agreed with my verdict. ‘It still drives really well and feels very stable. Race cars of this era were great to drive. In the ’90s, they started moving the driver backwards and towards the centre of the car, and really stiffening up the suspension. They weren’t as nice as this car to drive.’

During his time in the BTCC, Paul introduced a kerb-hopping driving style, which was much imitated. I asked him how that came about.

‘This BMW was one of the first sedans I raced,’ he said, ‘and I started by driving it just like a single-seater, smoothly and neatly. But then I saw Peter Brock chucking his car around over the bumps and chicanes and started to realise that these sedans needed a different style. I could never cut corners in the single-seaters, but with these cars you could save a lot of time by riding over the kerbs.’

Other drivers in Europe soon found out about his left-foot braking technique and started trying it for themselves. ‘Yes, they saw my car up on two wheels with the brake lights on and wondered what was going on,’ he laughed. ‘I started doing it because I had to work out how to get the best out of our front-wheel-drive Mondeo. I found that keeping a little brake pressure on through the corner while accelerating hard helped keep the nose in. It seemed to work, so eventually some of the other drivers tried it as well.’

With our track time finished we had another look over this beautifully preserved time machine. All the original heavy steel panels were in place as was the standard thick glass in the windows, just as the rules required. As Paul said, ‘These were real touring cars, unlike the ones we see today’. How true; this was very much a modified production road car.

As the years have gone on we have moved forward in lots of areas but at the same time lost the character and international flavour that this formula had. While I love new cars and new technology, the mechanical simplicity of this BMW requires more skill to get the best out of it than some of the modern race cars I’ve driven. I’m also reminded of the era when Paul made his name so famous – before in-car data logging was available. The truly talented, like Paul, had a big advantage over the mediocre drivers, as each had to rely on their own senses and gut instincts to get the most from the cars.

I left Hampton Downs feeling quite reflective. We lost a lot with the demise of Group A. Hopefully, at some point motorsport officials will look back and appreciate all the excitement that these cars brought us and bring back a brand-new series.

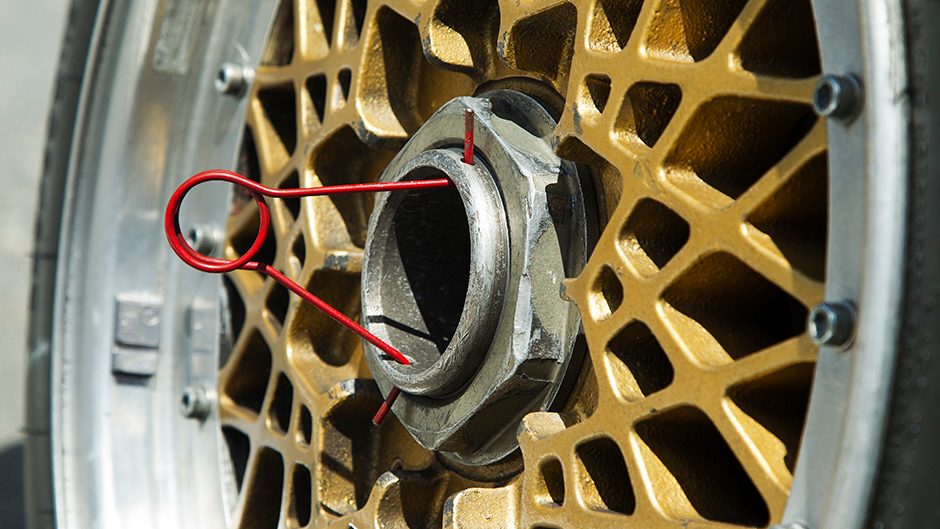

This car started as a bare shell shipped from the factory to Frank Gardner’s JPS racing team in Australia. It was built as a 325 model with a six-cylinder, 2.5-litre, 250bhp engine. Tony Longhurst drove the car in the up-to-2.5-litre class of the 1986 Australian Touring Car Championship, where it became a very successful package, and the talented Longhurst finished fifth overall. Clearly, the factory was watching developments in Australia, because it was during this period that it was engineering the M3 as a replacement for the 635 CSi. It would have a smaller and lighter, 300bhp, four-cylinder engine along with an increased track, but even so, such was the competence of the Gardner-developed 325 that the European factory engineers copied the suspension setup for their new M3s.

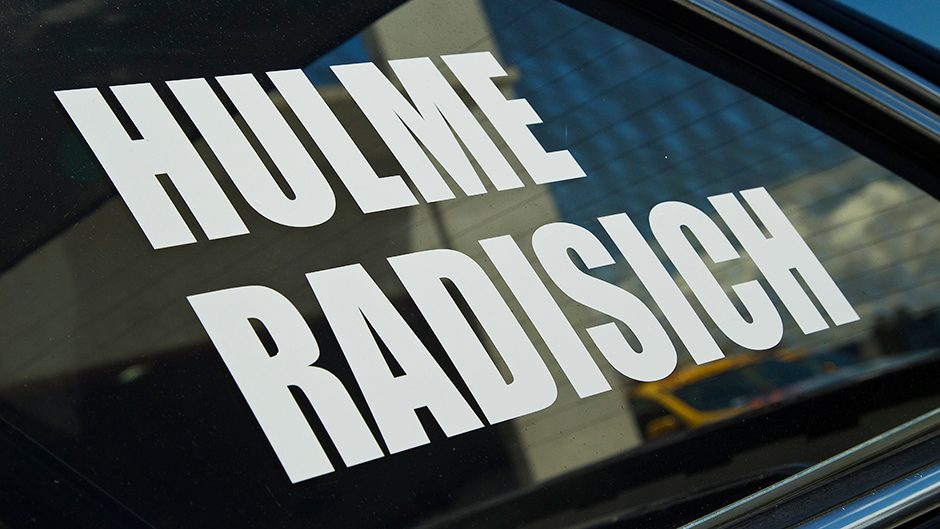

After its Aussie career was over, the 325 was purchased by Kiwi, Bill Bryce, who entered it in the Pukekohe three-hour race late in 1986, sharing the drive with Denny Hulme. Unfortunately, the car retired with a broken cam belt.

Bryce then entered the 325 in the ’87 Wellington street race but decided to put the young Paul Radisich in the car to co-drive alongside Patrick Finnauer. They finished 10th, outpaced by the newly developed M3s. In the next leg of the endurance series at Pukekohe, Paul was partnered with Denny Hulme. This time, the 325 finished a creditable sixth.

Bill Bryce then drove the car himself in the shorter B&H series races in 1988, but by that stage it was no longer competitive against the mighty M3s.