1963 Ford Lotus Cortina

Words/Photos: Richard Opie

The Ford Consul Cortina developed by Lotus was one of the first homologation specials. Here is its tale of race track domination and brand-enhancing appeal.

These days we barely bat an eyelid at the concept of a sedan packing serious performance credentials. And many of these blistered and boosted variants are developed with an influence from outside the usual design and engineering sphere. Think the AMGs, HSVs, Cosworths and M-divisions of this world. These outfits focus squarely on extracting peak performance from vehicles otherwise destined for more pedestrian endeavours. Such factory hot rods have forged a spot in the hearts of enthusiasts. It’s the genuine manifestation of the ‘win on Sunday, sell on Monday’ ethos, even if those days are now long gone.

Harking back to the 1960s, Ford, particularly the English arm, was hardly a brand you’d describe as being overly sexy or exciting. In fact it suffered from the opposite. Ford’s MO revolved around a ‘what you see is what you get’ mentality. While not quite utilitarian, Ford products were defined by function, honesty and being dependable; a somewhat formulaic means of mass transit. Cars like the Popular, Anglia, Zephyr and Consul handled the travel of sales reps and day-to-day family duties with perfect adequacy, until the Mk1 Cortina came swinging in 1962.

If the stylish three-box sedan went some way to enhancing Ford’s reputation as a car to be seen in, especially among the cityscapes, it was the development of the Lotus Cortina that totally flipped the script on the perception of Ford England.

Arguably the world’s first ‘homologation special,’ the intent for the Lotus Cortina was to win on track. But it also performed what some described as “the impossible”, transforming the Blue Oval’s staid image into something the buying public could aspire to.

The GT40 hadn’t yet tasted victory at Le Mans by this point, and nor had the Cosworth-Ford DFV become the hottest property on the F1 grid. Ford had never dabbled in motorsport with any gumption; the handful of rally victories in the late 50s never really captured the full attention of Ford’s head office dwellers. But as the 1960s dawned, Ford’s global ‘Total Performance’ initiative took effect, driven by those in Dearborn who, naturally, had swathes of brawny bent-eight powered machines to pick from. In the UK, pickings were somewhat slimmer and although the Cortina GT had tasted brief success, something spicier was required.

Enter one Walter Hayes. As the recently inducted head of Ford’s PR department, Hayes was adamant that motorsport was the path to image transformation. Coming on board in January of 1962, Hayes pounced on a fledgling relationship with the notably innovative but notoriously cash-strapped Lotus. The seeds had already been sown with Lotus. The Elan sports car was developed by an ex-Ford engineer, Ron Hickman, and founder, Colin Chapman, had already proposed that Ford manufacture the car. While this never happened, Ford did support the Elan in some capacity, with powertrain supply and marketing assistance.

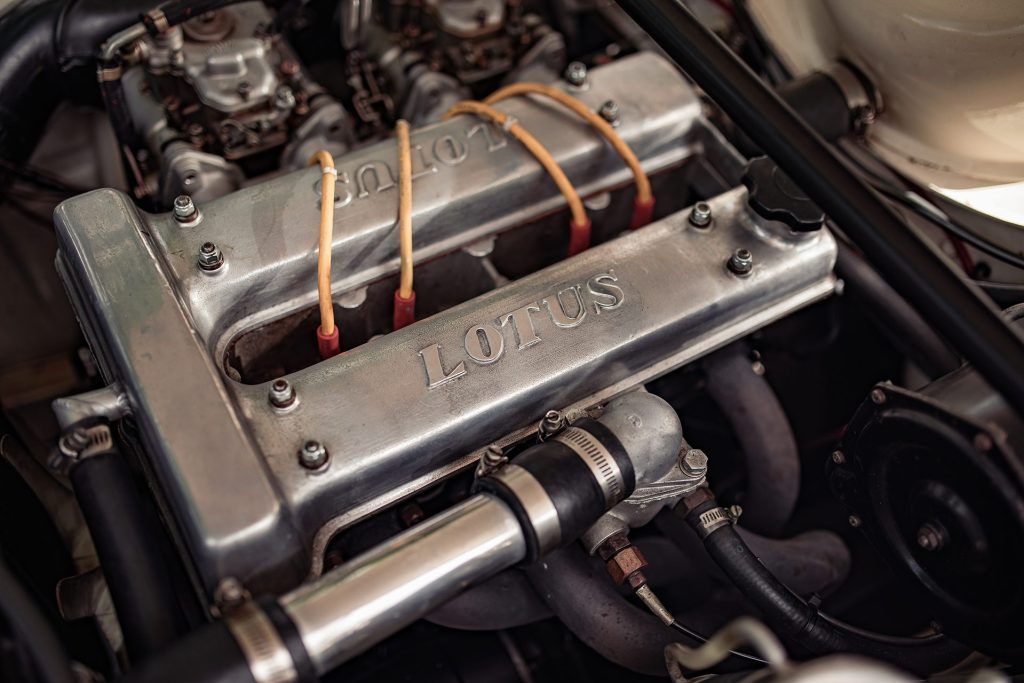

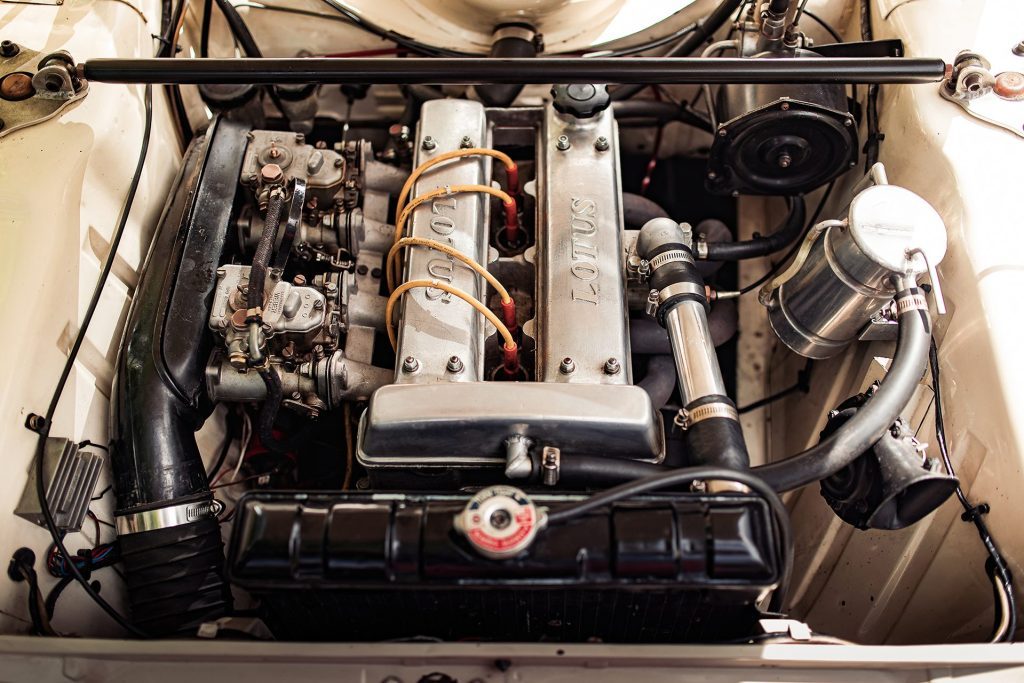

And then came the development of the Lotus Twin Cam, a solution to replacing the fragile Coventry Climax used in their Elite GT car. Chapman saw potential in the Ford ‘Kent’ block, a robust, oversquare design introduced with the Ford Anglia. The plan? Design a twin-cam head to fit the 1200cc Ford 109E engine and early in 1962 Lotus wheeled out a tired old Anglia, fitted with an over-bored variant of the 109E topped with Lotus’ freshly cast twin-cam head. Development would continue when Ford announced the 122E in May 1962, featuring a larger capacity and a five-bearing crankshaft. Within two weeks, Lotus had the twin-cam head adapted to this block, and installed in the back of a Lotus 23. Jim Clark took the diminutive sports racer out before the month was up, leading the car’s first race by a considerable margin before the exhaust manifold came loose, overcoming Clark with fumes and eventually leading to retirement. Development would continue throughout the year, although not as quickly as Chapman would have liked.

It was a meeting with Walter Hayes that would prove the catalyst for the Lotus Type 28 project, better known as the Lotus Cortina. Hayes had caught wind of what Lotus was doing with the Kent engine, and saw potential in creating a homologation model, aimed specifically at saloon car racing. The aim was to homologate 1000 road cars to comply with the FIA Group 2 rules concerning Production Touring Cars. Chapman, on the other hand, saw the relationship as a springboard for greater things for the Lotus marque, especially where finances were concerned. It was for all parties, a mutually beneficial arrangement and thus, the Lotus Cortina was conceived.

Ford would be responsible for supplying the painted, trimmed bodyshells, and Lotus the assembly. The engine that finally made its way between the struts of the Mark 1 Cortina two-door shells was uprated to 1558cc courtesy of some tweaks by Cosworth’s Keith Duckworth. Slung off the side was a pair of barking 40mm side-draft Weber carbs, endowing the Lotus Cortina with its distinctive rasp.

Not only was the engine bespoke, but the initial run of Lotus Cortinas was fitted with alloy bonnets and doors and an innovative but ultimately fragile coil spring conversion. This conversion utilised a coil-over shock at each end of the diff, itself located by an ‘A-frame’ bar that picked up on the diff housing before heading diagonally forwards in either direction to locate on the chassis. It worked well but was fragile, resulting in cracked diff housings under heavy usage. The later cars would revert to the traditional leaf sprung arrangement.

Christened the ‘Ford Consul Cortina developed by Lotus,’ the Lotus Cortina was unveiled to an adoring public at the October 1962 London Motor Show. With further refinement, the car finally made its way to the press in January 1963, but although production had commenced it was sluggish, with homologation only being attained by September of the same year, allowing the Lotus Cortina to enter competition.

In the car’s first outing at Oulton Park’s round of the BSCC, the Cortina took class honours, with ‘Gentleman’ Jack Sears leading home works teammate, Trevor Taylor. It set the scene for the Lotus Cortina’s motorsport legacy. The following year, 1964, it proved dominant, with Jim Clark taking overall honours, in a display of skill and versatility. Sir John Whitmore would go one better in 1965, taking out the European Saloon Car Championship in an Alan Mann-run entry, while Clark and Sears maintained momentum in the BSCC, ensuring the Cortina took class honours. Lotus Cortinas would go on to snare endurance titles, and even win rallies, before the car’s competition career was signed off in 1966, to make way for the boxy Mark 2 variant. In all, 3304 Lotus Cortinas would be produced from 1963 through to 1966, some destined to be race cars from the day they drove off the showroom floor. The Lotus Cortina redefined what a Ford was capable of.

All the way down in New Zealand, far from the glamour of the European Touring Car scene, the Mark 1 Lotus Cortina was also set to make an impact in the latter half of 1963. This example, belonging to Allan Woolf, one of New Zealand motorsport’s unsung personalities, BD9271 was among the very first of the six ‘pre Aeroflow’ Lotus Cortinas to arrive in New Zealand.

These cars featured a distinctive grille, narrower than their later brethren, as well as ‘Consul’ badging across the bonnet. These early cars had the ‘A frame’ rear suspension arrangement, as well as strengthening bars through the boot area, the battery tray relocated to the boot, lower ride height with the iconic 5.5-inch wide steel wheel, and of course the alloy- skinned bonnet and doors. All were painted Ermine white, with the famous Sherwood green stripe down the flanks and onto the stern of the Cortina, augmented by strategically placed Lotus badging.

The first owner of this car was Joe Hayes, of Papakura, a good friend of Woolf’s. “We used to co-drive together in endurance races, and run hillclimbs together,” explains Woolf. “He was in a Consul at one stage, and had a fast Mark 2

Zephyr. I fitted a Raymond Mays head with three carburetors, and it was a beautiful, silky car!”

In between farming, Hayes worked for Lees Brothers, a Papakura Ford dealership, and had managed to secure one of those six initial Lotus Cortinas destined for New Zealand. “Joe was too busy to run the car in, so the wife and I took the car for a run to Matamata on D-plates,” smiles Woolf, before explaining how great the Cortina looked alongside the other cars they were passing. He also noted how the upholstery was a cut above that of a normal Cortina, revelling in how the airy cabin of the Lotus-tuned Ford was a great place for a bit of motoring.

“On the standard camshafts, it was a brilliant road car, but the gearbox would take you to 60mph in first which wasn’t well suited to our hilly roads.”

The Cortina was purchased with the intent to race. “Hayes was a handy driver,” explains Woolf, “and the first event with the car was a three-hour race at Pukekohe. After that they’d just run it in anything and everything, from saloon car racing to hillclimbs.”

Interestingly, Woolf never raced the car until he’d own it some decades later but as is the nature of competition cars it’d find its way through a number of hands, traversing the country and ending up in the South Island, where Woolf’s son-in-law, Paul Adams, would acquire the Cortina as part of a deal for a rally car.

“It was in pretty good shape when I bought it off Paul,” Woolf says. “Someone had installed steel doors on it, and it had a leaf spring conversion on the rear. We’ve put it all back to how they were originally, but I did race it in classic events with the leaf springs.”

“I just enjoyed the thing, and I still do,” Woolf says of his experience with the Lotus. It’s not a totally standard car either, featuring a specification that’s true to how it was when Woolf was still running in classic events. “It’s got some cams in it, which spoils it a bit as a road car because they come on at 3000rpm, but you can always drop down a gear, can’t you?”

For just about any enthusiast, the Lotus Cortina is a car of unmistakable provenance. It’s the blueprint of the modern performance saloon, and while its stats are somewhat wanting by today’s standards, it’s a machine that simply commands respect. If it wasn’t for the likes of Jim Clark dangling a wheel of the little Cortina precariously over a corner apex, there simply wouldn’t be the legions of Fast Ford fans that have aspired to Blue Oval ownership over the ensuing years.